June 10th, 2015.

4:00 am.

Waiting to hear about the stay of an execution.

Too late.

A noose tightened.

A rope snapped.

A life ended before it ever really began.

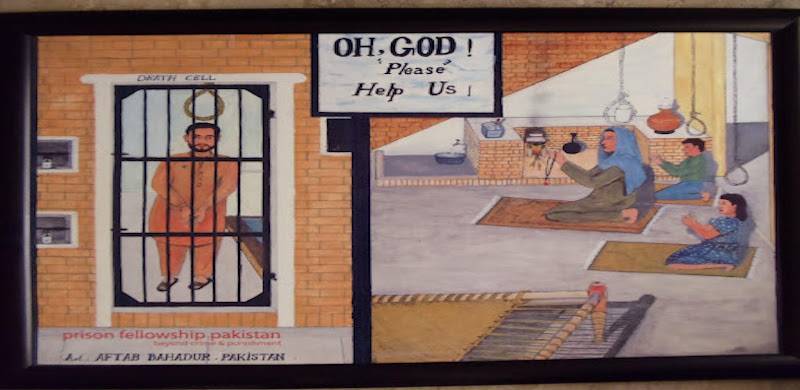

Aftab Masih Bahadur was a talented artist and a favourite amongst the staff at the jail where he spent over half his life. He wasn’t that educated so he articulated his feelings through art. He had been issued so many death warrants that he had lost count. But he did not lose hope, till the last day, that his truth would see the light of day and he would be set free.

I never met Aftab. I found out about him half a decade after he had already been executed. Because I work for a non-profit organization based in Lahore that represents the most vulnerable Pakistani prisoners facing the harshest punishments, at home and abroad. I had the privilege of going over his records, case transcripts and conversations.

The overwhelming impression I got was of Aftab being a sweet boy with a tragic fate. At 15 years of age in 1992, he was wrongly convicted of the murder of a woman and her two children in Anarkali where he worked as a plumber apprentice. He was arrested and taken to the crime scene where his fingers were forcibly dipped in oil and his prints planted on the cupboard. He was tortured, his family members were detained and some were also tortured to force a confession out of him. He eventually gave in.

The key eyewitness who placed him at the crime scene later retracted his statement. But it was only after Aftab had already wasted away in jail for almost 23 years.

The government of Pakistan ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Cruel Inhuman and Degrading Treatment (UNCAT) in 2010, making it legally binding. The National Action Plan for Human Rights, introduced by the Federal Ministry for Human Rights in February 2016, set a six-month deadline to pass the Torture, Custodial Death, and Custodial Rape (Prevention and Punishment) Bill. Despite these developments, Pakistan has, to date, failed to enact any comprehensive domestic legislation to address torture. It has also failed to institute any independent investigation mechanism to inquire into the use of police torture. A Yale University and Justice Project Pakistan study of 1,867 Medico Legal Documents in the District of Faisalabad between 2006 to 2012 discovered conclusive signs of torture in 1,424 cases.

In addition to the routine use of torture, the lack of forensics leads to unjust outcomes. Aftab was convicted based on a torture-induced confession and planted evidence. He was also a juvenile. Yet, his case went through speedy trial courts and the Supreme Appellate Court upheld the ruling.

There are only two fully functional Forensic Science Agencies in Pakistan to cater to the criminal justice needs of over 200 million people. As a result, the police resort to torture and harassment instead of proper investigative work supplemented by forensics. This then leads to people being wrongfully sentenced.

Aftab was an easy target since he belonged to a religious minority and was poor. When a JPP investigator visited him in jail, he once shyly asked for some oil and garlic so he could add tarka to his food. This little anecdote has stuck with me more than anything else. We don’t realize how cruelly prison deprives people of basic life pleasures.

Sentencing someone to death should not be this easy. There are countless others like Aftab languishing in prisons across Pakistan, and there will be many more unless torture is criminalized and the use of forensics normalized.

The witness who gave the false testimony against Aftab carried the guilt. On the eve of Aftab’s execution, he banged the prison gate, screaming “I lied, I lied!” Aftab’s co-accused was saved from execution after the promise of blood money but, due to non-payment, he was eventually taken to the gallows. He had requested his apology to be relayed to Aftab.

Aftab Masih Bahadur is now six feet under. On this International Day in Support of Torture Victims, lets not forget him and others like him. We must criminalize torture.

4:00 am.

Waiting to hear about the stay of an execution.

Too late.

A noose tightened.

A rope snapped.

A life ended before it ever really began.

Aftab Masih Bahadur was a talented artist and a favourite amongst the staff at the jail where he spent over half his life. He wasn’t that educated so he articulated his feelings through art. He had been issued so many death warrants that he had lost count. But he did not lose hope, till the last day, that his truth would see the light of day and he would be set free.

I never met Aftab. I found out about him half a decade after he had already been executed. Because I work for a non-profit organization based in Lahore that represents the most vulnerable Pakistani prisoners facing the harshest punishments, at home and abroad. I had the privilege of going over his records, case transcripts and conversations.

The overwhelming impression I got was of Aftab being a sweet boy with a tragic fate. At 15 years of age in 1992, he was wrongly convicted of the murder of a woman and her two children in Anarkali where he worked as a plumber apprentice. He was arrested and taken to the crime scene where his fingers were forcibly dipped in oil and his prints planted on the cupboard. He was tortured, his family members were detained and some were also tortured to force a confession out of him. He eventually gave in.

The key eyewitness who placed him at the crime scene later retracted his statement. But it was only after Aftab had already wasted away in jail for almost 23 years.

The government of Pakistan ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Cruel Inhuman and Degrading Treatment (UNCAT) in 2010, making it legally binding. The National Action Plan for Human Rights, introduced by the Federal Ministry for Human Rights in February 2016, set a six-month deadline to pass the Torture, Custodial Death, and Custodial Rape (Prevention and Punishment) Bill. Despite these developments, Pakistan has, to date, failed to enact any comprehensive domestic legislation to address torture. It has also failed to institute any independent investigation mechanism to inquire into the use of police torture. A Yale University and Justice Project Pakistan study of 1,867 Medico Legal Documents in the District of Faisalabad between 2006 to 2012 discovered conclusive signs of torture in 1,424 cases.

In addition to the routine use of torture, the lack of forensics leads to unjust outcomes. Aftab was convicted based on a torture-induced confession and planted evidence. He was also a juvenile. Yet, his case went through speedy trial courts and the Supreme Appellate Court upheld the ruling.

There are only two fully functional Forensic Science Agencies in Pakistan to cater to the criminal justice needs of over 200 million people. As a result, the police resort to torture and harassment instead of proper investigative work supplemented by forensics. This then leads to people being wrongfully sentenced.

Aftab was an easy target since he belonged to a religious minority and was poor. When a JPP investigator visited him in jail, he once shyly asked for some oil and garlic so he could add tarka to his food. This little anecdote has stuck with me more than anything else. We don’t realize how cruelly prison deprives people of basic life pleasures.

Sentencing someone to death should not be this easy. There are countless others like Aftab languishing in prisons across Pakistan, and there will be many more unless torture is criminalized and the use of forensics normalized.

The witness who gave the false testimony against Aftab carried the guilt. On the eve of Aftab’s execution, he banged the prison gate, screaming “I lied, I lied!” Aftab’s co-accused was saved from execution after the promise of blood money but, due to non-payment, he was eventually taken to the gallows. He had requested his apology to be relayed to Aftab.

Aftab Masih Bahadur is now six feet under. On this International Day in Support of Torture Victims, lets not forget him and others like him. We must criminalize torture.