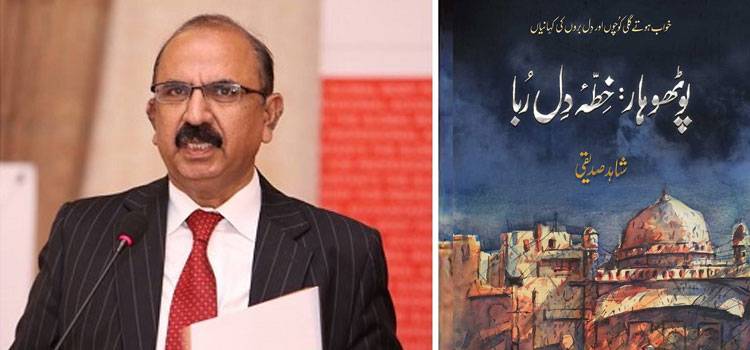

I met the author Dr. Shahid Siddiqui in the Allama Iqbal Open University when he was a lecturer in the English department in 1985. Although I worked in that university only for three months, I kept meeting him and saw his academic progress from his M.A. in the Teaching of English, from Britain, till his doctorate from Toronto University in Canada. However, I never discovered that he was a writer of Urdu till he presented his novel in that language to me. I was surprised at the skillful use that he made of Urdu and the air of sad romance which I found highly poignant and enjoyable. But even then, I did not know about his Urdu columns or about his interest in Potohar; nor, indeed, that he was born in Rawalpindi. This book, therefore, comes as a surprise. It was a very pleasant surprise, which I began on the assumption that it would be a collection of what is called belles lettres or some light-hearted glimpses of his childhood and friends. Instead, this book turned out to be the social history of Rawalpindi in particular, and the region of Potohar in general. And what a social history it is: highly readable, absorbing and spell-binding. In fact, I finished it in two days, though I read every word of most books I read—two days because I was doing other things too. Indeed, after a long time I found that I had not lost the capacity to curl up with a book at all odd hours and not bother too much about my usual routine.

The main characteristic of the book is that it is about characters who have made themselves memorable for the writer. While many of them are teachers in schools and lecturers in colleges – which is the world inhabited by the writer – not all of them belong to this world. There are, expectedly, the figures of his kind and caring father who took him to fairs in the village with him sitting on his shoulders and the mother who waved her grown up son goodbye and did not live to see him. There is his brother, Inam, whom he remembers as a unique personality; one who lived for others. However-- and this is what makes the book a social history—he also mentions the history of Lal Haveli, now famous as the residence of the politician Sheikh Rasheed. It was built by Dhan Raj, a very rich Hindu barrister before the 1947 Partition, for his beloved whose name was Budha Bai and who was a Muslim. Dhan Raj had fallen in love with her at a wedding where she danced, and he built this beautiful house to celebrate their love. In 1947, fearing for his life, Dhan Raj left for India. Had Budha Bai claimed that she was a Hindu, she could have retained the house. However, she said frankly that she shared everything with her husband except religion. Such facts are not known, and one is grateful to Shahid Siddiqui for bringing them out of oblivion. But the author does not write of the rich and powerful only. He also sketches a verbal portrait of Sakeena, a village girl who refuses to marry. Even for an educated, urban woman, this kind of iconoclasm of norms would have been difficult. Coming from a village girl who had never heard of feminist deconstruction of societal norms, it is truly outstanding. But Sakeena was no ordinary person. She travels all the way to the city where the author’s family had gone just to fulfill her promise to his mother to give them a homegrown mustard greens (saag).

Among the characters which throng his pages are those of his teachers in schools and lecturers in the college. In fact, some of his lecturers from Gordon College, where he studied for his M.A. in English literature, such as Khwaja Masood, Sajjad Haider and Aftab Iqbal Shameem, are well-known people at least in Pakistan. It is rather ironical that, though they have many students, nobody has written about them in ways which bring them back to life. Through the writer’s words we are ourselves transported to their classes which go on whether there is only one student or all of them. He has also written about Professor Fateh Mohammad Malik, known both in Pakistan and abroad as a writer and academic, as well as the Urdu poet Yusuf Hasan who was his friend and colleague in the Asghar Mall college of Rawalpindi.

One endearing feature of the book is that it allows one to connect with a distant past; one in which Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims lived together, often in a state of mutual accommodation, in the villages and towns of Potohar. Among these are people who migrated to India before or after Partition and rose to fame there. He mentions Madan Mohan, Gulzar, Sunil Datt, Meena Kumari, Anand Bakhshi, Balraj Sahni and Shilender. All of them rose to fame in Bollywood. Madan Mohan, originally from Chakwal, became a famous singer. Gulzar, whose name was Sampuran Singh, was born in Deena near Jhelum, and is famous now as a writer of lyrics, songs and also a writer and director of films. His film on Ghalib is widely acclaimed as the best work on the screen so far. Balraj, whose family was helped by a kindly Muslim village elder to escape to India, rose to fame as an actor; Meena Kumari, whose name was Mah Jabeen at birth, also became a film star. Anand Bakhshi, born in Rawalpindi, first joined the army but later found his true vocation in life as a writer of songs. Balraj Sahni, also born in a rich family of Rawalpindi, also became a film director. And Shilender, also born in a small house in Rawalpindi, wrote songs – though his dream of an egalitarian society made him aspire to creating an art movie for this purpose. This project did not succeed and he died.

In writing about these children of Potohar, Shahid Siddiqui has done an enormous service to the cause of those who believe in the possibility of peace and accommodation among the people of the Subcontinent. In any case it goes to the credit of the writer to rise above communal bias and treat all the children of the region with equal respect and attention.

The main character of the book, however, is not a human being but the city of Rawalpindi itself. Shahid Siddiqui describes it meticulously as if he is guiding the reader through its historical sites, showing them his houses, the streets he played in and the restaurants he sat in sipping hot tea and discussing literature, films and songs and whatever was going in in the country. One can breathe the air of Pindi, meet its people and find out what it is to be inundated with waves of nostalgia. Of course, the Pindi which Siddiqui evokes is no more. But if history is making an era come alive as it should be then that is what has been achieved in this book. Those of us who were young in the 1970s and 1980s might connect this Pindi with the one they have in their minds but it is reassuring that pictures of it exist in words which make this connection easier.

Shahid Siddiqui generally begins his sketches with a story or an anecdote from his own experience. For instance, he begins the sketch on Gulzar with a book which is about Gulzar’s work and which makes him drive all the way to Gulzar’s ancestral house in Deena in the evening. And in the end, there is a haunting nostalgia, a romantic sigh for the passing time which moves on and on. He is also very sensitive to the earth, the changing seasons, the sunshine, rain, the chill of winter and the blistering heat of summer. In short, the tangible world of Potohar, its nights and days, are always present in his writing and connect it to life as it is lived every day. And the overall impression created by his writings is of haunting nostalgia, of life and people elevated to a romantic plane of positivity which, in fact, we humans do not achieve—or, at least, most of us do not.

This, however, brings me to my criticism of some aspects of the book. It is, in a word, romantic and this sometimes makes one wonder whether reality is not being sugarcoated. For instance, he tells us that Master Fazal, his teacher of mathematics, was highly conscientious but his anxiety that his students did well and got scholarships made him beat them mercilessly (pp. 153-154). However, he is critical of the teachers of today who want their students to get A grades in O and A level examinations (p. 157). In what way are the desires of the teachers of the past different from those of today one may ask? Also, there is no condemnation of the cruelty of the teachers who administered corporal punishment. In fact, the romantic attitude of the writer portrays them only as dedicated and sincere figures which, we know from Ashfaq Ahmad’s story Gadariya, they certainly were. This romantic attitude towards the past prevents Shahid Siddiqui from telling us about the lecturers who did not teach well or not at all. One has heard so much about them that it is not credible that all lecturers were as dedicated and accomplished as the ones he has written about. The ones who were not have simply not been mentioned, so that one gets the impression that the past was a golden age and since then there has been a decline in everything.

The writer, despite his erudition, follows the debunked historical narrative of the Pakistani state as far as wars are concerned. For instance, he says that the 1965 war ‘’was imposed upon Pakistan” (p. 42) forgetting that, in fact, this war was initiated by Pakistan’s actions. Even in earlier wars, he uses discrepant criteria to praise or blame fighters. Thus, while the Khokars’ war of self-determination against Shahabuddin Ghauri is called a rebellion (baghawat), that of the Gakhars is praised (p. 318). Both were local tribes so, if the criterion was that the locals have the right to defend their land, both deserved approbation. But Ghauri is not condemned as a war monger probably because he too is a figure of praise in the Pakistani historical narrative.

These inconsistencies or differences of emphases are, however, not serious and substantial mistakes. These are minor lacunas in a work which is otherwise deserving of praise as a book of social history, regional history as well as literary prose. Its printing and binding are also excellent. It deserves to be read and enjoyed and I recommend it unreservedly to the general as well as the specialist reader. I hope students read this book too since they should be the ones to be inspired by such kind of writing. Perhaps, some day they too will record and preserve the past as Dr Shahid Siddiqui has done so well.

Title: Potohar: Ik Khitta-e-Dil Ruba

Author: Shahid Siddiqui

Publisher: Jhelum Book Corner

Year: 2022

Pages: 335

Price: PKR 1,195/--.

The main characteristic of the book is that it is about characters who have made themselves memorable for the writer. While many of them are teachers in schools and lecturers in colleges – which is the world inhabited by the writer – not all of them belong to this world. There are, expectedly, the figures of his kind and caring father who took him to fairs in the village with him sitting on his shoulders and the mother who waved her grown up son goodbye and did not live to see him. There is his brother, Inam, whom he remembers as a unique personality; one who lived for others. However-- and this is what makes the book a social history—he also mentions the history of Lal Haveli, now famous as the residence of the politician Sheikh Rasheed. It was built by Dhan Raj, a very rich Hindu barrister before the 1947 Partition, for his beloved whose name was Budha Bai and who was a Muslim. Dhan Raj had fallen in love with her at a wedding where she danced, and he built this beautiful house to celebrate their love. In 1947, fearing for his life, Dhan Raj left for India. Had Budha Bai claimed that she was a Hindu, she could have retained the house. However, she said frankly that she shared everything with her husband except religion. Such facts are not known, and one is grateful to Shahid Siddiqui for bringing them out of oblivion. But the author does not write of the rich and powerful only. He also sketches a verbal portrait of Sakeena, a village girl who refuses to marry. Even for an educated, urban woman, this kind of iconoclasm of norms would have been difficult. Coming from a village girl who had never heard of feminist deconstruction of societal norms, it is truly outstanding. But Sakeena was no ordinary person. She travels all the way to the city where the author’s family had gone just to fulfill her promise to his mother to give them a homegrown mustard greens (saag).

Among the characters which throng his pages are those of his teachers in schools and lecturers in the college. In fact, some of his lecturers from Gordon College, where he studied for his M.A. in English literature, such as Khwaja Masood, Sajjad Haider and Aftab Iqbal Shameem, are well-known people at least in Pakistan. It is rather ironical that, though they have many students, nobody has written about them in ways which bring them back to life. Through the writer’s words we are ourselves transported to their classes which go on whether there is only one student or all of them. He has also written about Professor Fateh Mohammad Malik, known both in Pakistan and abroad as a writer and academic, as well as the Urdu poet Yusuf Hasan who was his friend and colleague in the Asghar Mall college of Rawalpindi.

One endearing feature of the book is that it allows one to connect with a distant past; one in which Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims lived together, often in a state of mutual accommodation, in the villages and towns of Potohar. Among these are people who migrated to India before or after Partition and rose to fame there. He mentions Madan Mohan, Gulzar, Sunil Datt, Meena Kumari, Anand Bakhshi, Balraj Sahni and Shilender. All of them rose to fame in Bollywood. Madan Mohan, originally from Chakwal, became a famous singer. Gulzar, whose name was Sampuran Singh, was born in Deena near Jhelum, and is famous now as a writer of lyrics, songs and also a writer and director of films. His film on Ghalib is widely acclaimed as the best work on the screen so far. Balraj, whose family was helped by a kindly Muslim village elder to escape to India, rose to fame as an actor; Meena Kumari, whose name was Mah Jabeen at birth, also became a film star. Anand Bakhshi, born in Rawalpindi, first joined the army but later found his true vocation in life as a writer of songs. Balraj Sahni, also born in a rich family of Rawalpindi, also became a film director. And Shilender, also born in a small house in Rawalpindi, wrote songs – though his dream of an egalitarian society made him aspire to creating an art movie for this purpose. This project did not succeed and he died.

In writing about these children of Potohar, Shahid Siddiqui has done an enormous service to the cause of those who believe in the possibility of peace and accommodation among the people of the Subcontinent. In any case it goes to the credit of the writer to rise above communal bias and treat all the children of the region with equal respect and attention.

The main character of the book, however, is not a human being but the city of Rawalpindi itself. Shahid Siddiqui describes it meticulously as if he is guiding the reader through its historical sites, showing them his houses, the streets he played in and the restaurants he sat in sipping hot tea and discussing literature, films and songs and whatever was going in in the country. One can breathe the air of Pindi, meet its people and find out what it is to be inundated with waves of nostalgia. Of course, the Pindi which Siddiqui evokes is no more. But if history is making an era come alive as it should be then that is what has been achieved in this book. Those of us who were young in the 1970s and 1980s might connect this Pindi with the one they have in their minds but it is reassuring that pictures of it exist in words which make this connection easier.

Shahid Siddiqui generally begins his sketches with a story or an anecdote from his own experience. For instance, he begins the sketch on Gulzar with a book which is about Gulzar’s work and which makes him drive all the way to Gulzar’s ancestral house in Deena in the evening. And in the end, there is a haunting nostalgia, a romantic sigh for the passing time which moves on and on. He is also very sensitive to the earth, the changing seasons, the sunshine, rain, the chill of winter and the blistering heat of summer. In short, the tangible world of Potohar, its nights and days, are always present in his writing and connect it to life as it is lived every day. And the overall impression created by his writings is of haunting nostalgia, of life and people elevated to a romantic plane of positivity which, in fact, we humans do not achieve—or, at least, most of us do not.

This, however, brings me to my criticism of some aspects of the book. It is, in a word, romantic and this sometimes makes one wonder whether reality is not being sugarcoated. For instance, he tells us that Master Fazal, his teacher of mathematics, was highly conscientious but his anxiety that his students did well and got scholarships made him beat them mercilessly (pp. 153-154). However, he is critical of the teachers of today who want their students to get A grades in O and A level examinations (p. 157). In what way are the desires of the teachers of the past different from those of today one may ask? Also, there is no condemnation of the cruelty of the teachers who administered corporal punishment. In fact, the romantic attitude of the writer portrays them only as dedicated and sincere figures which, we know from Ashfaq Ahmad’s story Gadariya, they certainly were. This romantic attitude towards the past prevents Shahid Siddiqui from telling us about the lecturers who did not teach well or not at all. One has heard so much about them that it is not credible that all lecturers were as dedicated and accomplished as the ones he has written about. The ones who were not have simply not been mentioned, so that one gets the impression that the past was a golden age and since then there has been a decline in everything.

The writer, despite his erudition, follows the debunked historical narrative of the Pakistani state as far as wars are concerned. For instance, he says that the 1965 war ‘’was imposed upon Pakistan” (p. 42) forgetting that, in fact, this war was initiated by Pakistan’s actions. Even in earlier wars, he uses discrepant criteria to praise or blame fighters. Thus, while the Khokars’ war of self-determination against Shahabuddin Ghauri is called a rebellion (baghawat), that of the Gakhars is praised (p. 318). Both were local tribes so, if the criterion was that the locals have the right to defend their land, both deserved approbation. But Ghauri is not condemned as a war monger probably because he too is a figure of praise in the Pakistani historical narrative.

These inconsistencies or differences of emphases are, however, not serious and substantial mistakes. These are minor lacunas in a work which is otherwise deserving of praise as a book of social history, regional history as well as literary prose. Its printing and binding are also excellent. It deserves to be read and enjoyed and I recommend it unreservedly to the general as well as the specialist reader. I hope students read this book too since they should be the ones to be inspired by such kind of writing. Perhaps, some day they too will record and preserve the past as Dr Shahid Siddiqui has done so well.