Before writers embark on the long and arduous yet thrilling journey that is writing a story, script, or screenplay, they must have a solid story idea. Once your story is solid, new writers may take longer to reach the right producer – but it will happen.

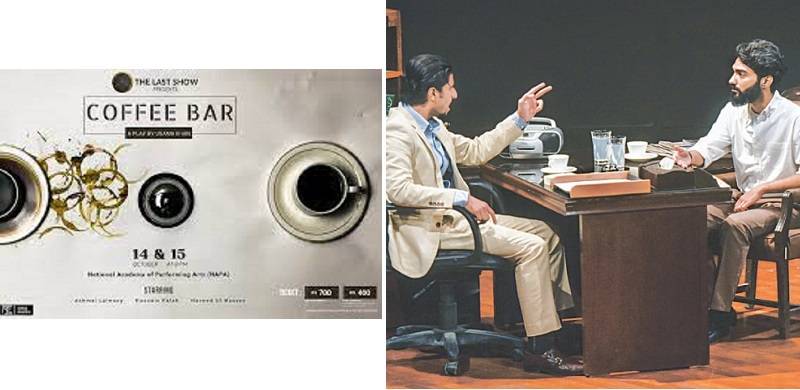

The National Academy of Performing Arts (NAPA) recently presented a play that was centered on writers and producers, and everything that happens to the script between them. Directed by Usama Khan, a recent graduate of the academy, the play starred Ashmal Lalwany, Husnain Falak and Naveed-ul-Hassan, and was a translated rendition of a multi-faceted Arabic play of the same name.

As a writer myself, the play is extremely pertinent as I felt a fraction of the larger narrative tied around it. The stage opened to an old song playing in the background, Tum Zid Toh Kar Rahey Ho, with plush leather couches and a sleek office desk, where the producer (played by Husnain Falak) is seated.

The story revolves around a playwright (Ashmal Lalwany), who has reached out to several producers to present his play. The plot takes off when he is called in for a meeting to discuss the technicalities of the play – director, actors, outreach plan, etc. The producer appreciates the play but rambles on to avoid the real discussion. Intermittently, he calls the waiter (Naveed Ul Hassan) for coffee and sandwiches.

The real problem begins when the producer shares his opinion about the usage of vulgar words in the script, where he categorically mentions that it is downright ‘disrespectful and crass’ to bring such words into a masterpiece of the script. The argument gets heated as the writer is forced to change his script. The verbal skirmish takes on a fiery turn when the writer refuses to do so, saying “all the plays of legendary writers like Chekhov, Kafka, Bernard Shaw, and Hemingway were ruined, because they spoke the truth. One of our writers was also inspired by them – Manto."

The writer laments over the misrepresentation of the plays, stating, “Art means presenting the real picture with several angles to allow the audience to decide whether the work is commendable. It is not the job of the writers to only paint a pretty picture.” He questions, “Where is our freedom, and why are our words not protected?”

The producer insists on condemning the works of all the above, accusing the present one of representing someone's vested interests, and wraps the argument on the fact that the script doesn’t belong to the writer once it enters ‘Coffee Bar’. He force-sends the writer to have a "kehwa, or shikanjibeen, or chai," or offers chocolates instead, but receives no coffee. Here, the writer undergoes a horrendous incident with the waiter (numb and mum) in a separate room that he would never forget. The producer is sure that the writer will succumb to pressure, and predictably, that is what happens. He doesn’t get coffee. He doesn’t get his word out. He conforms to the authority of the producer.

As soon as he agrees to add the recommendations – a historical event, an item song – calling them minute edits, all is well for the producer. This is what all amateur writers go through. The problem is the pressure to ensure you are doing something completely commercially viable. The writers AND producers feel and know it is wrong but they succumb to it because they think it would be more commercially acceptable and fiscally viable, leaving logic in the hands of ‘creative liberties’.

The director substantiated this further, “When I read this play for the first time, my initial realisation was that if I rewrite this play, it will be easier for people to relate with the characters. Additionally, I also came across a situation where writers are forced to write, but this is not about commercial viability only. It is broader than that. Now they are being forced to write a narrative-based story to preach to the spectators, especially the youth. I wanted to show the audience that we, as a nation, are stuck in an endless loop, and in my opinion, we can't do anything to free ourselves. There is no hope for change if you go against the flow, they can even inhumanly force you to change your perspective of life.”

Is this a usual practice in the entertainment industry where writers' work doesn’t come across as authentic versions because they've had to change their texts?

“Yes, it occurs quite often in our entertainment industry. Merely because of commercial purposes, the real art that has been written never gets portrayed. For instance, we have a recent example of Zindagi Tamasha, a pure art film that hasn’t been released because there wasn't a commercial aspect while it was also written on a sensitive topic. This doesn’t give writers any room to bring forth good scripts as they are sure they won’t be accepted. So what the audience is left with is an amalgamation of fictional pieces woven into a mindless drama script with the same plots one-hero-one-villain stories. But it wasn't like this always. PTV proves to be the biggest example of the golden times we witnessed when we produced great dramas on diverse topics but at that time, we had legendary writers like Ashfaq Ahmed, Kamal Ahmed Rizvi, Hashim Nadeem, and many more,” Usama Khan discoursed at his directorial debut.

Technically speaking, the lighting was dramatically on-spot, encapsulating the dearth of good scripts and the gloom and doom that surrounds the industry. The metaphorical lyrics of the song played at the back clearly translated into the writer’s expression of grief, the producer’s Catch-22 situation, and the waiter’s muteness in the whole happenstance. The difficult dynamics of the relationship and their inter-dependency was clearly and subliminally portrayed. The set was immaculate, each piece hinting at the hidden truth and the world’s denial, whether it was the painting, the books on the shelf, or the absolute authority that leather furniture commands. The trio of actors was on-point with their acting and dialogue delivery, even the waiter, who made his strong presence felt, despite the eerie silence.

By and large, Coffee Bar definitely highlighted the power that visual media has on the audience. In a culture like ours, it pretty much shapes our views from a young age and has the muscle to promote change. So why not make it a medium to spill the truth? It’s time for the powerful entertainment industry to shoulder some responsibility to help bring a positive social change in attitudes after watching a progressive piece of any art form.

The director said that there might be more screenings of the play soon.

So, this one must not be missed, especially when NAPA is exploring and encouraging new artists every day.

The National Academy of Performing Arts (NAPA) recently presented a play that was centered on writers and producers, and everything that happens to the script between them. Directed by Usama Khan, a recent graduate of the academy, the play starred Ashmal Lalwany, Husnain Falak and Naveed-ul-Hassan, and was a translated rendition of a multi-faceted Arabic play of the same name.

As a writer myself, the play is extremely pertinent as I felt a fraction of the larger narrative tied around it. The stage opened to an old song playing in the background, Tum Zid Toh Kar Rahey Ho, with plush leather couches and a sleek office desk, where the producer (played by Husnain Falak) is seated.

The story revolves around a playwright (Ashmal Lalwany), who has reached out to several producers to present his play. The plot takes off when he is called in for a meeting to discuss the technicalities of the play – director, actors, outreach plan, etc. The producer appreciates the play but rambles on to avoid the real discussion. Intermittently, he calls the waiter (Naveed Ul Hassan) for coffee and sandwiches.

As soon as he agrees to add the recommendations – a historical event, an item song – calling them minute edits, all is well for the producer

The real problem begins when the producer shares his opinion about the usage of vulgar words in the script, where he categorically mentions that it is downright ‘disrespectful and crass’ to bring such words into a masterpiece of the script. The argument gets heated as the writer is forced to change his script. The verbal skirmish takes on a fiery turn when the writer refuses to do so, saying “all the plays of legendary writers like Chekhov, Kafka, Bernard Shaw, and Hemingway were ruined, because they spoke the truth. One of our writers was also inspired by them – Manto."

The writer laments over the misrepresentation of the plays, stating, “Art means presenting the real picture with several angles to allow the audience to decide whether the work is commendable. It is not the job of the writers to only paint a pretty picture.” He questions, “Where is our freedom, and why are our words not protected?”

The producer insists on condemning the works of all the above, accusing the present one of representing someone's vested interests, and wraps the argument on the fact that the script doesn’t belong to the writer once it enters ‘Coffee Bar’. He force-sends the writer to have a "kehwa, or shikanjibeen, or chai," or offers chocolates instead, but receives no coffee. Here, the writer undergoes a horrendous incident with the waiter (numb and mum) in a separate room that he would never forget. The producer is sure that the writer will succumb to pressure, and predictably, that is what happens. He doesn’t get coffee. He doesn’t get his word out. He conforms to the authority of the producer.

As soon as he agrees to add the recommendations – a historical event, an item song – calling them minute edits, all is well for the producer. This is what all amateur writers go through. The problem is the pressure to ensure you are doing something completely commercially viable. The writers AND producers feel and know it is wrong but they succumb to it because they think it would be more commercially acceptable and fiscally viable, leaving logic in the hands of ‘creative liberties’.

The director substantiated this further, “When I read this play for the first time, my initial realisation was that if I rewrite this play, it will be easier for people to relate with the characters. Additionally, I also came across a situation where writers are forced to write, but this is not about commercial viability only. It is broader than that. Now they are being forced to write a narrative-based story to preach to the spectators, especially the youth. I wanted to show the audience that we, as a nation, are stuck in an endless loop, and in my opinion, we can't do anything to free ourselves. There is no hope for change if you go against the flow, they can even inhumanly force you to change your perspective of life.”

Is this a usual practice in the entertainment industry where writers' work doesn’t come across as authentic versions because they've had to change their texts?

“Yes, it occurs quite often in our entertainment industry. Merely because of commercial purposes, the real art that has been written never gets portrayed. For instance, we have a recent example of Zindagi Tamasha, a pure art film that hasn’t been released because there wasn't a commercial aspect while it was also written on a sensitive topic. This doesn’t give writers any room to bring forth good scripts as they are sure they won’t be accepted. So what the audience is left with is an amalgamation of fictional pieces woven into a mindless drama script with the same plots one-hero-one-villain stories. But it wasn't like this always. PTV proves to be the biggest example of the golden times we witnessed when we produced great dramas on diverse topics but at that time, we had legendary writers like Ashfaq Ahmed, Kamal Ahmed Rizvi, Hashim Nadeem, and many more,” Usama Khan discoursed at his directorial debut.

Technically speaking, the lighting was dramatically on-spot, encapsulating the dearth of good scripts and the gloom and doom that surrounds the industry. The metaphorical lyrics of the song played at the back clearly translated into the writer’s expression of grief, the producer’s Catch-22 situation, and the waiter’s muteness in the whole happenstance. The difficult dynamics of the relationship and their inter-dependency was clearly and subliminally portrayed. The set was immaculate, each piece hinting at the hidden truth and the world’s denial, whether it was the painting, the books on the shelf, or the absolute authority that leather furniture commands. The trio of actors was on-point with their acting and dialogue delivery, even the waiter, who made his strong presence felt, despite the eerie silence.

By and large, Coffee Bar definitely highlighted the power that visual media has on the audience. In a culture like ours, it pretty much shapes our views from a young age and has the muscle to promote change. So why not make it a medium to spill the truth? It’s time for the powerful entertainment industry to shoulder some responsibility to help bring a positive social change in attitudes after watching a progressive piece of any art form.

The director said that there might be more screenings of the play soon.

So, this one must not be missed, especially when NAPA is exploring and encouraging new artists every day.