“If we are going to allow ourselves to be influenced by the public opinion that can be created in the name of religion when we know that religion has nothing to do with the matter, I think we must have the courage to say, ‘No, we are not going to be frightened by that’,” suggested Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

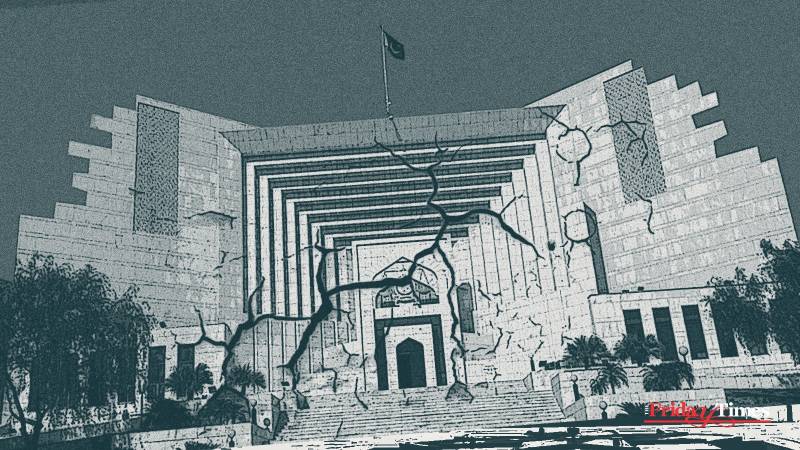

Chief Justice Qazi Faez Isa’s decision to omit paragraph 42 of his judgment in review under pressure from the religious parties and goons who mobbed the Supreme Court is just the latest in a series of capitulations by the Pakistani state in face of public opinion created in the name of religion which started on September 7th 1974 – that infamous day when Pakistan’s unthinking parliament, led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (and completely supported by Opposition leaders Wali Khan and Mufti Mahmood) decided to declare Ahmadis non-Muslim. The list of votes is a shameful reminder of what happens when we allow uninformed public opinion formed in the name of religion to dictate the questions of public policy. The vote was unanimous thus making the entire country complicit in what can only be described as a crime against humanity.

It bears repeating that it was not always like this. As Dr Ali Usman Qasmi writes in his book Qaum Mulk Sultanat: Citizenship and National Belonging In Pakistan, when the issue was first raised in 1953, the Prime Minister’s office had circulated a memorandum which stated that declaring Ahmadis non-Muslim would violate the longstanding policy of the Muslim League to not get into sectarian questions, referring to Jinnah’s decision to veto a resolution to expel Ahmadis from the Muslim League.

On 30 July 1944, Maulana Abdul Hamid Badayuni had presented a resolution calling for such expulsion, but Jinnah had forced him to withdraw it. For this, he earned the sobriquet Kafir-e-Azam or the great infidel. If there was any ambiguity about the status of Ahmadis in the League, it was laid to rest by Jinnah when he deputed Sir Zafrullah Khan to first represent Pakistan as counsel before the Boundary Commission and then appointed him the first foreign minister of Pakistan. All this changed in 1974 when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto chose to follow the disastrous course of giving into public opinion formed on religion alone and in 1984 when General Zia’s government made it a crime for an Ahmadi to profess his faith openly.

The ongoing persecution of the Ahmadi community not only violates the spirit of Jinnah’s vision, which arguably was dead on arrival, but also places the country in clear violation of its international obligations under the Genocide Convention and the Rome Statute.

This makes what happened in the Supreme Court on 22 August 2024 all the more tragic. Paragraph 42 of the judgment was hardly controversial. It merely stated that Ahmadis had the right to practise their religion in the privacy of their homes and in their places of worship, which cannot be called mosques under law. Article 20 as well as the Objectives Resolution gives every citizen the right to profess, practise and propagate their religion as well as develop their cultures freely and openly. Paragraph 42 was only allowing the Ahmadis the right to practise their religion in the confines of their own homes and places of worship. By omitting this paragraph, the Supreme Court has essentially criminalised the very practice of Ahmadi faith. Religious freedom in Pakistan has been decisively abolished. It also means that Supreme Court is now no different from any lower court in Pakistan and that any possibility of justice and fair play from the apex court has been foreclosed for all practical purposes. This will not stop at Ahmadis. Nor will it stop with religious minorities. Shias will be next. After that the Barelvis will turn against Deobandis. It will lead to the dissolution of the state. The die has been cast.

Article II Subsection c of the Genocide Convention states that “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”

What is now being done to Ahmadis in Pakistan is genocide under the Convention. All it will take is for any of the 200 countries of the world to bring a case against the country for violating the genocide convention before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Alternatively the matter could come from the General Assembly of the UN or even the Security Council. Of course ICJ has no means of enforcing its judgment but should the ICJ find against Pakistan, which in all likelihood it will, the consequences for Pakistan will be severe. While the ICJ cannot impose criminal penalties, a ruling against Pakistan for genocide would lead to international condemnation, damaging its diplomatic relations and standing in the global community.

The court could order Pakistan to provide reparations, cease genocidal acts, and make systemic reforms to protect the Ahmadi community, placing immense pressure on the government. Such a ruling could trigger economic sanctions, trade restrictions, and the loss of foreign aid, further isolating the country. More damningly, a ruling of genocide could open the door for referrals to the International Criminal Court (ICC), where individual officials responsible for these acts could face prosecution. The ripple effects would be profound, threatening the country's international legitimacy and economic stability, with far-reaching consequences for its legal, political, and social fabric.

What Pakistan does to the Ahmadis is severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of the fundamental rules of international law and is an institutionalized regime of religious discrimination and bigotry.

Pakistan’s policy makers and judges might not take the threat of referrals to the ICC seriously because but it is a very real possibility. The Rome Statute does allow for officials of the non state parties to be held accountable for genocide. 7(1)e of the Rome Statute states that “imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law.” What Pakistan does to the Ahmadis is severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of the fundamental rules of international law and is an institutionalized regime of religious discrimination and bigotry.

If there is any ambiguity about its application to Ahmadis, 7(1)h of the Rome Statute lays down that “persecution against any identifiable group or collectivity on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender as defined in paragraph 3, or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law, in connection with any act referred to in this paragraph or any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court.” These are classified as crimes against humanity, which are separate from war crimes. The entire Pakistani state is complicit in this and will be held accountable, sooner or later.

Pakistan's judiciary and policymakers must, therefore, reflect on the dangerous precedent they are setting by allowing this persecution to continue. The ongoing persecution of the Ahmadi community not only violates the spirit of Jinnah’s vision, which arguably was dead on arrival, but also places the country in clear violation of its international obligations under the Genocide Convention and the Rome Statute.

The implications are stark: continued failure to protect religious minorities will erode Pakistan’s standing in the global community and expose its leaders to unprecedented legal and diplomatic consequences. Now more than ever, Pakistan must choose whether to reaffirm its commitment to justice, equality, and the rule of law or face the dire repercussions of allowing bigotry to dictate public policy. History will judge this moment harshly if Pakistan fails to act and put an end to this persecution now.