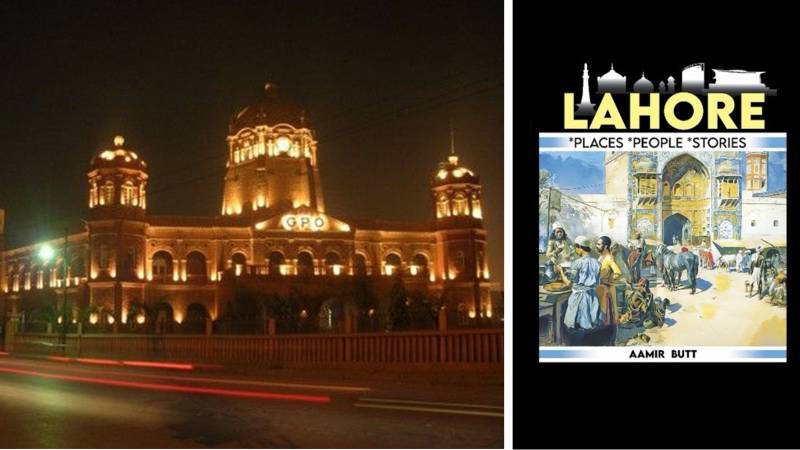

Aamir Butt is a medical doctor based in the UK, but he visits Lahore at least once every year. He was born in Lahore but grew up in Rawalpindi. A great connoisseur of poetry, he has now published a labour of love devoted to Lahore. The book is written in short writeups, some less than two pages. The ambition is to capture as multifaceted charms of Lahore in both historical and contemporary terms as possible. The author acquits himself with flying colours. He relies on anecdotal as well as scholarly evidence to portray places and people and tell stories associated with Lahore. Famously one short chapter is titled in the catchphrase Lhore Lhore Aye (Lahore is Lahore).

In the English language, Pran Nevile chronicled in his, Lahore: A Sentimental Journey (1993), pre-partition cosmopolitan Lahore when it basked in the full glory of British patronage. Nevile wrote that Lhore Lhore Aye gained currency in the beginning of the 20th century when rural Punjabis started visiting Lahore and were dazzled by the buildings, roads and parks the British had built.

Butt, a Jinnah faithful, takes forward the story of Lahore from there onwards and thoughtfully pays homage to some non-Muslims whose favours to Lahore have survived all attempts to erase the memory of their presence. Special mention is made of Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1799 – 1839), the only native Punjabi who established his kingdom centred on Lahore. He was a shrewd politician, a just and benevolent patronage of all communities who were represented at his court and in the army, while his personal indulgences included drugs and a harem consisting of a range of women.

Butt acknowledges the contributions of Sir Ganga Ram, a Hindu, who left built a hospital, a medical college, many roads and buildings but whose descendants were driven out in 1947 from Jinnah’s Pakistan.

The Ravi river, an integral and organic part of Lahore’s topography went to India because of the 1960 Indus Water Treaty

Regarding the origins of Lahore, the author takes up the legend that it was founded by Lava or Loh, son of Lord Ram, but argues that its original founders could be Bhatti Rajputs. Some other sources are also mentioned which take back the origins of Lahore 10 thousand years! That sounds fantastical but the author is quite generous on drawing upon such scholars. Also mentioned is that Lahore was once upon a time as magnificent as Isfahan, the capital of the Safavids, and that in John Milton’s long poem Paradise Lost, Lahore was celebrated as a great city of the world.

Lahore once again captured the fancy of the world when in 1955 Hollywood's MGM came to Lahore to shoot scenes for Bhowani Junction. Earlier Jawaharlal Nehru, adhering to his non-alignment policy, had refused permission to shoot the film in India, but Pakistan welcomed it and it brought among others Eva Gardner, one of the most beautiful women of the world, to play the lead role. The story revolves around Eva Gardner as an Anglo-Indian raven hair beauty courted by three suitors, a Sikh, a fellow Anglo-Indian and a British army officer.

The plot develops around the freedom movement, and was shot mostly at the Lahore Railway Station. Hundreds of extras were dressed up as coolies including my late friend Abdul Majid in Stockholm who died some years ago. Most of these young men were interested in seeing Eva Gardner. Many remember seeing her walking on the Mall Road in shorts which made them go crazy and dizzy.

Lahore suffered a tragedy deriving from the fundamentally divisive nature of the two-nation theory which in 1947 not only divided men and women based on religion but also the waters of Punjab. The Ravi river, an integral and organic part of Lahore’s topography went to India because of the 1960 Indus Water Treaty between India and Pakistan which allocated the waters of Ravi to India. Today, the Ravi riverbed is practically dry except during the monsoons.

Continuing along the historical track, Butt takes us to the grave of Bamba Sutherland, the daughter of Dilip Singh the youngest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, buried in the Gora Kabristan in the upper-class Gulberg locality of Lahore. We learn about the distinctive class of Red Sufis, a rebel tendency, who in contrast to most Sufis who preferred white or green attire used red clothes. Shah Hussain (born 1538) was a famous Red Sufi. He would dance and behave unconventionally, which included having as a lover a beautiful Brahmin boy Madho. Both are buried side by side in a shrine in Baghbanpura and an annual festival continues to attract thousands of devotees who dance Dhamal to the beat of drums.

Among the people whose presence in Lahore left an indelible mark on its literary history include Allama Iqbal, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Sahir Ludhianvi, Amrita Pritam and Saadat Hasan Manto – none of whom was Lahore born but their memory is inextricably linked to their presence in Lahore.

I hope the author will expand the next edition on this section because his grip on literature is impressive. Krishan Chander, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Zaheer Kaashmir, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi, Ustad Daman and many others need to be presented to the new generations. Fortunately, the Progressive Writers’ Association is mentioned and inevitably the India later Pak Tea House where its sessions were held is also noted. Music director Khawaja Khurshid Anwar is mentioned. So is the singer, Mohammad Rafi. That list needs also to be expanded. There are many other interesting stories, places and people presented by the author.

The author courageously corrects a misconception about the role of Mohammad Ali Jinnah during the case in which Ilam Din was convicted for murdering Rajpal, a Hindu in 1926 who published a scurrilous book "Rangila Rasul," defaming Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). The fake story popular in Pakistan is that Jinnah volunteered to defend him! He advised Ilam Din to deny that he assassinated Rajpal, but the latter refused to do so. This is hagiographical stuff presented in a Lollywood film. The objective truth is far removed from it.

At the lower trial court, Mian Farrukh Hussain had defended Ilam Din arguing that he was not guilty, and that the case was framed by the police based on questionable witness accounts. The court had dismissed his plea and sentenced him to death. Jinnah was hired by Muslim notables of Lahore to appeal in the Lahore High Court. Jinnah stayed in the famous Falleti’s Hotel and argued before the superior court that Ilam Din was a young man of 19 who was incensed by the fact that his Prophet (PBUH) had been insulted. Therefore, the sentence should be commuted from death penalty to some lighter punishment. To Butt’s research can be added that Jinnah charged his usual fees, and his stay was also fully covered by donations by Lahore Muslims.

The high court upheld the verdict of the trial court and Ilam Din was hanged in Mianwali Jail in 1929. Leading Muslims attended his funeral, and he was declared a martyr. Interestingly Ilam Din maintained throughout the trial that he had not killed Rajpal, and the police had framed him.

Overall, the book is a most welcome contribution to the multifarious charms of Lahore.