With ShoaibMansoor continuing his foray into progressive, nay reformist, filmmaking, Verna was understandably the most anticipated film of the year. A female-led film depicting a rape survivor in society ripe for violent misogyny was destined to take Pakistani cinema to the next level, to add to the upward curve that it has been traversing. A more pertinent issue could not have been taken up in a country where a woman is raped every two hours.

That Verna was banned – albeit temporarily, and only intended to be shielded from a particular demographic – was precisely the promotion it needed, especially after a Censor Board official had said: “The general plot of the movie revolves around rape, which we consider to be unacceptable.”

And yet the film – all facets and pretty much every individual associated with it – blows it big time.

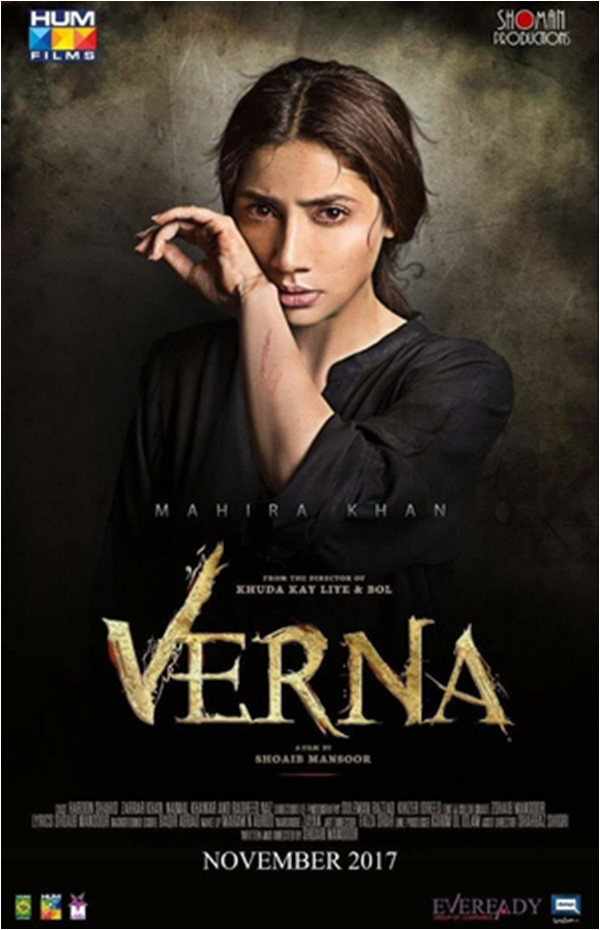

The story revolves around Sara (Mahira Khan) who is kidnapped and raped by the governor’s son in Islamabad. Sara is kidnapped in front of her husband Aami (Haroon Shahid), a polio victim, who along with his family struggles to cope with accepting the reality once Sara returns home.

While both families – the parents and the in-laws – are adamant that hushing up about the entire episode is the prudent way to go, Sara will do all in her power to seek justice.

What follows is a hotchpotch of social commentary, courtroom drama, a quasi-thriller, all of which turn out to be a facade for what the film eventually self-identifies as: a laughably simplistic critique on Pakistani politics – an ostensible disclosure on Power Di Game.

While Verna would make Bol look Oscar-worthy, if there was one unquestionable downside to Shoaib Mansoor’s previous offering, it was that he opened too many fronts and took up too many causes for a single film. That was surprising considering how clear and coherent Khuda Ke Liye had been in its aim, and has hence been by far the most successful in driving home its point.

Verna could have been the depiction of Pakistani attitudes towards rape, harassment and violence against women. It could have been a denunciation of the whole concept of ‘honour’ that has been entwined with the female anatomy. It could very well have been a political drama underscoring how power continues to be misused by the elite. And perhaps it should’ve stuck to being a revenge thriller – of which perhaps Verna showed the most promise.

But in uninhibitedly aiming to be all of the above, not only does the film turn out to be none of them, it actually puts together a cringeworthy, clueless catastrophe that actually manages to make a mockery of its own subject matter and not the society that it seemingly intended to condemn.

There are many scenes where one isn’t sure if the societal attitudes are designed to be slated, or if the film is joining in the victim-blaming.

And yet, there are clear indicators of Verna’s position on key debates. For instance, how a woman dresses up has got nothing to do with rape; that the clergy has been instrumental in creating inertia against women’s rights; that honour has no correlation with the female body and isn’t damaged through violence against women; that it’s never okay for a husband to hit his wife, who can – and does – give him a smack in return.

But at the same time the film, inadvertently, promotes regressive attitudes towards divorce by ensuring that the protagonist ‘returns to her man’, despite everything downright despicable that he had said and done – and despite that fact that the film in a scene ascertains that his reactions to his wife being raped actually made him worse than the rapist.

At one point when Sara is telling Aami that she would only return to him once she has settled her score, the husband asks with a straight face: iss mein kitna time lagay ga? (how much time would it take?)

Similarly, for a film that poses to present a revisionist approach towards honour, it somehow allows all of its characters – including the lead – to let an evidence be decisive in the court proceedings, because any probe would’ve being ‘damaging to the honour’ of the family.

The only unequivocal condemnation Verna seems to offer is reserved for orthodox interpretations of religion, which is a shame considering Shoaib Mansoor has already dedicated an entire, perfectly executed film to that very subject.

Not only does the film fail to convincingly take a progressive stand for women’s rights – let alone rape survivors – it manages to endorse regressive ideas like the stereotyping of Pashtuns, extrajudicial and self-inflicted tribal justice and rendering law itself superfluous.

Perhaps Verna’s biggest crime is the unabashed disdain it reserves for a polio victim, which is not only unnecessary, it is actually blatantly counterproductive. Underscoring the insecurities of a healthy man, the fragility of the male ego, while depicting a headstrong woman taking a firm stand against a husband without any physical disabilities would’ve been far more profound.

Even so, Verna might still have worked had it not been for the sheer mediocrity of acting at display. Barring Zarar Khan, who nails his character as the governor’s son, none of the actors is half as convincing for a script that was always going to demand the very best. This is most unfortunate for Mahira Khan, for not only was her character going to be the heart and soul of the movie, but as Pakistan’s biggest female film-star she was also the torchbearer for a sustained future of women-oriented movies.

What the film intends to convey is often demonstrated through the punchline at the end. In Verna’s case it was an urge to ‘not vote’ for the powerful elite who rape women. Little wonder that it is being interpreted by some as political propaganda and not a serious take on the gravest of issues in Pakistan.

That Verna was banned – albeit temporarily, and only intended to be shielded from a particular demographic – was precisely the promotion it needed, especially after a Censor Board official had said: “The general plot of the movie revolves around rape, which we consider to be unacceptable.”

And yet the film – all facets and pretty much every individual associated with it – blows it big time.

The story revolves around Sara (Mahira Khan) who is kidnapped and raped by the governor’s son in Islamabad. Sara is kidnapped in front of her husband Aami (Haroon Shahid), a polio victim, who along with his family struggles to cope with accepting the reality once Sara returns home.

While both families – the parents and the in-laws – are adamant that hushing up about the entire episode is the prudent way to go, Sara will do all in her power to seek justice.

What follows is a hotchpotch of social commentary, courtroom drama, a quasi-thriller, all of which turn out to be a facade for what the film eventually self-identifies as: a laughably simplistic critique on Pakistani politics – an ostensible disclosure on Power Di Game.

While Verna would make Bol look Oscar-worthy, if there was one unquestionable downside to Shoaib Mansoor’s previous offering, it was that he opened too many fronts and took up too many causes for a single film. That was surprising considering how clear and coherent Khuda Ke Liye had been in its aim, and has hence been by far the most successful in driving home its point.

The film, inadvertently, promotes regressive attitudes towards divorce by ensuring that the protagonist 'returns to her man', despite everything downright despicable that he had said and done

Verna could have been the depiction of Pakistani attitudes towards rape, harassment and violence against women. It could have been a denunciation of the whole concept of ‘honour’ that has been entwined with the female anatomy. It could very well have been a political drama underscoring how power continues to be misused by the elite. And perhaps it should’ve stuck to being a revenge thriller – of which perhaps Verna showed the most promise.

But in uninhibitedly aiming to be all of the above, not only does the film turn out to be none of them, it actually puts together a cringeworthy, clueless catastrophe that actually manages to make a mockery of its own subject matter and not the society that it seemingly intended to condemn.

There are many scenes where one isn’t sure if the societal attitudes are designed to be slated, or if the film is joining in the victim-blaming.

And yet, there are clear indicators of Verna’s position on key debates. For instance, how a woman dresses up has got nothing to do with rape; that the clergy has been instrumental in creating inertia against women’s rights; that honour has no correlation with the female body and isn’t damaged through violence against women; that it’s never okay for a husband to hit his wife, who can – and does – give him a smack in return.

But at the same time the film, inadvertently, promotes regressive attitudes towards divorce by ensuring that the protagonist ‘returns to her man’, despite everything downright despicable that he had said and done – and despite that fact that the film in a scene ascertains that his reactions to his wife being raped actually made him worse than the rapist.

At one point when Sara is telling Aami that she would only return to him once she has settled her score, the husband asks with a straight face: iss mein kitna time lagay ga? (how much time would it take?)

Similarly, for a film that poses to present a revisionist approach towards honour, it somehow allows all of its characters – including the lead – to let an evidence be decisive in the court proceedings, because any probe would’ve being ‘damaging to the honour’ of the family.

The only unequivocal condemnation Verna seems to offer is reserved for orthodox interpretations of religion, which is a shame considering Shoaib Mansoor has already dedicated an entire, perfectly executed film to that very subject.

Not only does the film fail to convincingly take a progressive stand for women’s rights – let alone rape survivors – it manages to endorse regressive ideas like the stereotyping of Pashtuns, extrajudicial and self-inflicted tribal justice and rendering law itself superfluous.

Perhaps Verna’s biggest crime is the unabashed disdain it reserves for a polio victim, which is not only unnecessary, it is actually blatantly counterproductive. Underscoring the insecurities of a healthy man, the fragility of the male ego, while depicting a headstrong woman taking a firm stand against a husband without any physical disabilities would’ve been far more profound.

Even so, Verna might still have worked had it not been for the sheer mediocrity of acting at display. Barring Zarar Khan, who nails his character as the governor’s son, none of the actors is half as convincing for a script that was always going to demand the very best. This is most unfortunate for Mahira Khan, for not only was her character going to be the heart and soul of the movie, but as Pakistan’s biggest female film-star she was also the torchbearer for a sustained future of women-oriented movies.

What the film intends to convey is often demonstrated through the punchline at the end. In Verna’s case it was an urge to ‘not vote’ for the powerful elite who rape women. Little wonder that it is being interpreted by some as political propaganda and not a serious take on the gravest of issues in Pakistan.