My time in New York is swiftly coming to an end for this year. Look out Lahore, because like a migratory bird of prey I am venturing back for the winter to where the temperature is more suitable and the gossip more venomous (boo!). I do enjoy the late fall in America, though; the way the leaves turn into orange and gold; the way all the Starbucks start putting pumpkin flavours in everything to make you feel both fat and well; the way the streets begin to look like the transitional scenes from Home Alone 2, decorated in fairy lights and twinkling tinsel for the upcoming holidays.

But really, after you’ve seen one pumpkin you’ve seen them all, and the smoggy sunsets of Lahore are calling to me like a siren (of death). Still, before I left I made a promise to myself that I would go and see a show on Michelangelo’s drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition had been in the ether for months. Even when I was traveling around Italy and Spain last summer and marveling at the art, occasionally I would come across an empty space on the wall with a note to say the piece was on loan in New York for an upcoming exhibition.

As one does, I began imagining this nameless faceless show to be the show to end all the shows – the definitive ranking of the old masters’ mastery. To be fair, that is exactly how it has been sold. Vast sections of NY streets are now covered with large laser-printed ads for “Micheangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer”, a title that makes him sound like a gay fashion icon (which of course is not inaccurate for Michelangelo, tbh).

The show is seminal for reasons beyond its brand-name recognition. It brings together over 200 works – more than 150 of which are Michelangelo’s – from over 50 collections around the world, and is the largest ever exhibition of his drawings to date. The fact that they are drawings is important, I think, and made the exhibition a must-see for me. There is an immediacy to the artist’s hand that is often obscured in other mediums. It’s not just about colour choices or compositional continuity, factors which can be outright overpowering in a painting. No, it is something far more simple, far more delicate. It is about line, and that element can’t hide in a drawing – especially for a man who insisted he was a sculptor and not a painter. And it is for that reason that I was so invested in staying on to see the show. Given that it is only on for three months (the exact length of time the curators deemed it safe to keep the fragile works on paper on display), I am glad I did.

Although Michelangelo himself would have you believe he arrived in art history fully formed, the truth is he did have some extensive training, which is on display in the first few rooms of the show. There are copies of the works of more famous painters of the time, as well as the earliest known work by the artist himself. I was relieved to see that even someone who was known during his own lifetime as ‘the Divine One’ could demonstrate some hesitancy with his brushwork and penmanship, but you can be sure it didn’t last for long.

The next few rooms show some startling preparatory drawings for works that would come to define his career – from Medici commissions to Vatican projects – and what is fascinating is how the figure he is drawing gradually stops resembling anyone real but rather becomes an idealised form that looks like marble, as much a confirmation as one needs to know that Michelangelo considered sculpture his first love.

Some rooms further along in the exhibit, there is a nice but slightly underwhelming small-scale replica of the Sistine chapel installed on the ceiling. I confess that having seen the real one scarcely a few months ago I know I probably shouldn’t judge it, but I did. By this stage there are fewer spontaneous drawings and far more that look to have been the product of a large studio set-up, which I suppose is natural for someone who had just been told to paint the face of God and then decorate the rest of the building too.

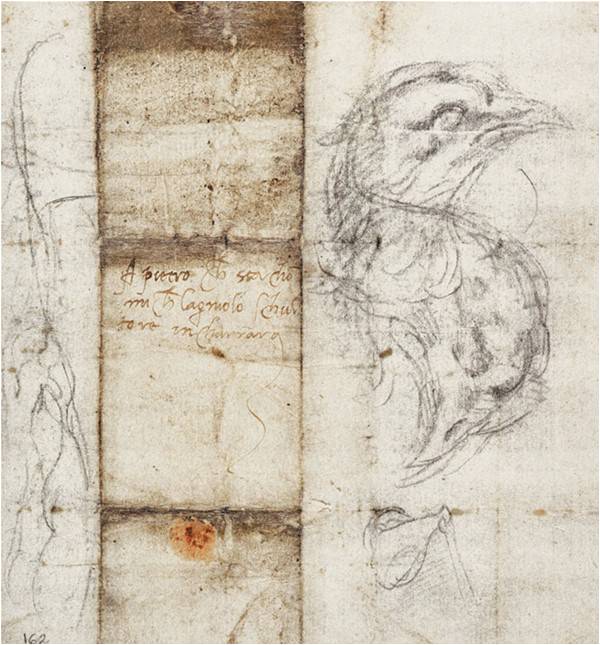

I have written to you before of the time that I managed to actually hold a Michelangelo drawing in my hand as a student. When I turned the corner of one of the last rooms I saw the drawing again, bathed in light and this time behind a series of glass partitions. I greeted it like I suppose one would an old lover, with an intimacy and affection which few else could claim.

As I was leaving I stopped at the end to see the list of many institutions and collections who had made the show possible, and noted without surprise that the Louvre Museum in Paris was one of the big hitters. You have probably heard that the Louvre is just opening up its first satellite museum in Abu Dhabi (the long-awaited return on the Emirates’ 1 billion euro investment) and I couldn’t help but wonder how much of the wonderful show that I had seen would be allowed anywhere near that space. Would they object to the nudes? The depiction of religious figures? Nipples in general? It frustrated me, because so many more people around the world should be able to see the marvels of this exhibition, not only to see the marvelous talent of the Divine One, but to see first-hand through gesture and line that he was, after all, just a man. And isn’t that the most amazing thing of all?

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com

But really, after you’ve seen one pumpkin you’ve seen them all, and the smoggy sunsets of Lahore are calling to me like a siren (of death). Still, before I left I made a promise to myself that I would go and see a show on Michelangelo’s drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition had been in the ether for months. Even when I was traveling around Italy and Spain last summer and marveling at the art, occasionally I would come across an empty space on the wall with a note to say the piece was on loan in New York for an upcoming exhibition.

NY streets are now covered with large ads for "Micheangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer", a title that makes him sounds like a gay fashion icon

As one does, I began imagining this nameless faceless show to be the show to end all the shows – the definitive ranking of the old masters’ mastery. To be fair, that is exactly how it has been sold. Vast sections of NY streets are now covered with large laser-printed ads for “Micheangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer”, a title that makes him sound like a gay fashion icon (which of course is not inaccurate for Michelangelo, tbh).

The show is seminal for reasons beyond its brand-name recognition. It brings together over 200 works – more than 150 of which are Michelangelo’s – from over 50 collections around the world, and is the largest ever exhibition of his drawings to date. The fact that they are drawings is important, I think, and made the exhibition a must-see for me. There is an immediacy to the artist’s hand that is often obscured in other mediums. It’s not just about colour choices or compositional continuity, factors which can be outright overpowering in a painting. No, it is something far more simple, far more delicate. It is about line, and that element can’t hide in a drawing – especially for a man who insisted he was a sculptor and not a painter. And it is for that reason that I was so invested in staying on to see the show. Given that it is only on for three months (the exact length of time the curators deemed it safe to keep the fragile works on paper on display), I am glad I did.

Although Michelangelo himself would have you believe he arrived in art history fully formed, the truth is he did have some extensive training, which is on display in the first few rooms of the show. There are copies of the works of more famous painters of the time, as well as the earliest known work by the artist himself. I was relieved to see that even someone who was known during his own lifetime as ‘the Divine One’ could demonstrate some hesitancy with his brushwork and penmanship, but you can be sure it didn’t last for long.

The next few rooms show some startling preparatory drawings for works that would come to define his career – from Medici commissions to Vatican projects – and what is fascinating is how the figure he is drawing gradually stops resembling anyone real but rather becomes an idealised form that looks like marble, as much a confirmation as one needs to know that Michelangelo considered sculpture his first love.

Some rooms further along in the exhibit, there is a nice but slightly underwhelming small-scale replica of the Sistine chapel installed on the ceiling. I confess that having seen the real one scarcely a few months ago I know I probably shouldn’t judge it, but I did. By this stage there are fewer spontaneous drawings and far more that look to have been the product of a large studio set-up, which I suppose is natural for someone who had just been told to paint the face of God and then decorate the rest of the building too.

I have written to you before of the time that I managed to actually hold a Michelangelo drawing in my hand as a student. When I turned the corner of one of the last rooms I saw the drawing again, bathed in light and this time behind a series of glass partitions. I greeted it like I suppose one would an old lover, with an intimacy and affection which few else could claim.

As I was leaving I stopped at the end to see the list of many institutions and collections who had made the show possible, and noted without surprise that the Louvre Museum in Paris was one of the big hitters. You have probably heard that the Louvre is just opening up its first satellite museum in Abu Dhabi (the long-awaited return on the Emirates’ 1 billion euro investment) and I couldn’t help but wonder how much of the wonderful show that I had seen would be allowed anywhere near that space. Would they object to the nudes? The depiction of religious figures? Nipples in general? It frustrated me, because so many more people around the world should be able to see the marvels of this exhibition, not only to see the marvelous talent of the Divine One, but to see first-hand through gesture and line that he was, after all, just a man. And isn’t that the most amazing thing of all?

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com