The Heart of Asia conference in Islamabad has rekindled hopes for a revival of dialogue for regional peace. Pakistan, India and Afghanistan form the axis of animosity that has plagued the region with chronic conflicts. Since its inception, Pakistan has been sandwiched between conflicts on its eastern and western borders, and that has taken a toll on peace and human development.

Two weeks ago, I visited Kabul as part of a “track 1.5/II” dialogue facilitated by two leading civil society organizations of Pakistan and Afghanistan – the Centre for Research and Security Studies in Islamabad, and Duran in Kabul. Our eight-member delegation represented various shades of civil society, including media, non-governmental organizations and the academia. During the visit, the delegation had intensive discussions with the Afghan civil society, media and political leadership, including Afghan Chief Executive Dr Abdullah Abdullah and the former president Hamid Karzai. The interaction with a cross-section of the Afghan society provided us with a unique opportunity to understand the dynamics of the conflict and the various perspectives on both sides.

Perceptions and narratives have evolved over decades, because of long rivalries. A blend of genuine concerns and baseless misperceptions has resulted in a pervasive mistrust on both sides. From the civil society to the top political leadership, almost everyone in Afghanistan believes that the Pakistani establishment is singularly responsible for their plight. While they appreciated Pakistan’s generous hospitality to millions of Afghan refugees for decades, they firmly believed that elements responsible for terrorist activities in Afghanistan enjoyed cross-border support. The Haqqani group and Pakistani Taliban were frequently referred as violent outfits coddled by the Pakistani establishment. When we asked them about the presence of Mullah Fazlullah in Afghanistan, the Afghan leadership asked how they could kill Fazlullah – who sneaked into its territory on two years ago and has been hiding in Taliban-controlled areas, enjoying support from the other side of the border – when Pakistan could not kill the Haqqanis. They criticized the presence, coronation and unconfirmed killing of Mullah Mansoor in Pakistan, and an unbridled Quetta Shura. They said leaders of some proscribed outfits operate openly in the country, and roam around like celebrities.

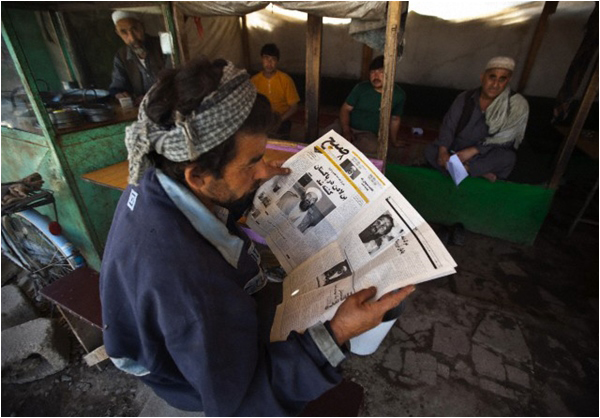

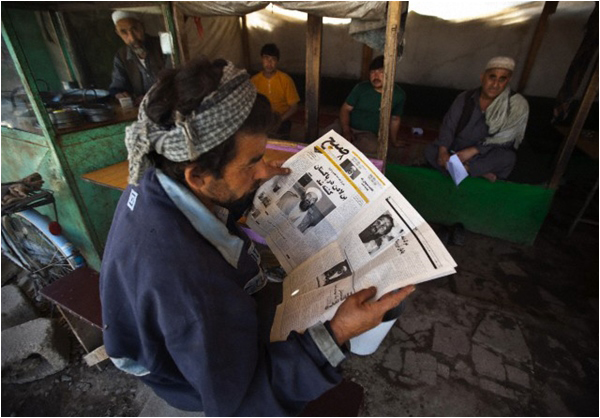

Afghanistan’s cordial relations with India shaped the contours of its foreign policy since the partition of the subcontinent. India’s influence in Afghanistan was quite evident in the Afghan media. The Indian ambassador’s scathing statement on the Nawaz-Ghani meeting in Paris was the banner headline of Afghanistan Times. The leading newspaper frequently carried anti-Pakistan news and statements prominently. The Afghan leadership is not sheepish about this at all. It asserts that as a sovereign country it is their right to have relations with any country to serve its interests.

A personal friend, who is a native of Kabul, took me around the city and shared spellbinding memories of how the city was reduced to rubble by the battling mujahideen groups in the 1990s, followed by the spate of brutality unleashed during the Taliban era. He said he was not a communist, nor did he espouse any left-leaning political ideology, but he believed that the communist rule was the best period of Afghanistan’s recent history. He showed me the square where former president Dr Najeeb was savagely hanged by the Taliban after his murder. According to him, Afghanistan was a thriving country during those days, when education and health were the responsibility of the state, and women enjoyed unprecedented freedom. Having spent several years in Pakistan, he had a deep affection for the country, but he was candid in accepting that Pakistan’s image had been tarnished in Afghanistan – because of false propaganda, but also because of some bitter truths. Pakistan is viewed as an unkind neighbor that sided with international powers to weaken Afghanistan under one or the other pretext since the 1980s.

Amid these concerns, the Afghan president’s participation in the Heart of Asia conference in Islamabad and the revival of the frozen peace process is an opportunity. But dialogue between the two countries should not remain confined to political leaders. It should include cultural exchanges between the civil society, traders, and other segments of the society. After spending five days in Kabul, I returned with deeper worries. Geopolitical realities appeared far more complex than I had imagined.

“The US, the UK, Pakistan and some Arab countries have treated us like a non-entity in past,” an Afghan leader said. “They ought to respect our sovereignty now.”

The author is an analyst and the head of Strengthening Participatory Organization

Two weeks ago, I visited Kabul as part of a “track 1.5/II” dialogue facilitated by two leading civil society organizations of Pakistan and Afghanistan – the Centre for Research and Security Studies in Islamabad, and Duran in Kabul. Our eight-member delegation represented various shades of civil society, including media, non-governmental organizations and the academia. During the visit, the delegation had intensive discussions with the Afghan civil society, media and political leadership, including Afghan Chief Executive Dr Abdullah Abdullah and the former president Hamid Karzai. The interaction with a cross-section of the Afghan society provided us with a unique opportunity to understand the dynamics of the conflict and the various perspectives on both sides.

I returned from Afghanistan with deeper worries

Perceptions and narratives have evolved over decades, because of long rivalries. A blend of genuine concerns and baseless misperceptions has resulted in a pervasive mistrust on both sides. From the civil society to the top political leadership, almost everyone in Afghanistan believes that the Pakistani establishment is singularly responsible for their plight. While they appreciated Pakistan’s generous hospitality to millions of Afghan refugees for decades, they firmly believed that elements responsible for terrorist activities in Afghanistan enjoyed cross-border support. The Haqqani group and Pakistani Taliban were frequently referred as violent outfits coddled by the Pakistani establishment. When we asked them about the presence of Mullah Fazlullah in Afghanistan, the Afghan leadership asked how they could kill Fazlullah – who sneaked into its territory on two years ago and has been hiding in Taliban-controlled areas, enjoying support from the other side of the border – when Pakistan could not kill the Haqqanis. They criticized the presence, coronation and unconfirmed killing of Mullah Mansoor in Pakistan, and an unbridled Quetta Shura. They said leaders of some proscribed outfits operate openly in the country, and roam around like celebrities.

Afghanistan’s cordial relations with India shaped the contours of its foreign policy since the partition of the subcontinent. India’s influence in Afghanistan was quite evident in the Afghan media. The Indian ambassador’s scathing statement on the Nawaz-Ghani meeting in Paris was the banner headline of Afghanistan Times. The leading newspaper frequently carried anti-Pakistan news and statements prominently. The Afghan leadership is not sheepish about this at all. It asserts that as a sovereign country it is their right to have relations with any country to serve its interests.

A personal friend, who is a native of Kabul, took me around the city and shared spellbinding memories of how the city was reduced to rubble by the battling mujahideen groups in the 1990s, followed by the spate of brutality unleashed during the Taliban era. He said he was not a communist, nor did he espouse any left-leaning political ideology, but he believed that the communist rule was the best period of Afghanistan’s recent history. He showed me the square where former president Dr Najeeb was savagely hanged by the Taliban after his murder. According to him, Afghanistan was a thriving country during those days, when education and health were the responsibility of the state, and women enjoyed unprecedented freedom. Having spent several years in Pakistan, he had a deep affection for the country, but he was candid in accepting that Pakistan’s image had been tarnished in Afghanistan – because of false propaganda, but also because of some bitter truths. Pakistan is viewed as an unkind neighbor that sided with international powers to weaken Afghanistan under one or the other pretext since the 1980s.

Amid these concerns, the Afghan president’s participation in the Heart of Asia conference in Islamabad and the revival of the frozen peace process is an opportunity. But dialogue between the two countries should not remain confined to political leaders. It should include cultural exchanges between the civil society, traders, and other segments of the society. After spending five days in Kabul, I returned with deeper worries. Geopolitical realities appeared far more complex than I had imagined.

“The US, the UK, Pakistan and some Arab countries have treated us like a non-entity in past,” an Afghan leader said. “They ought to respect our sovereignty now.”

The author is an analyst and the head of Strengthening Participatory Organization