One of the greatest things a person can have in their life is a good relationship with their parents. A relationship centred on love, respect, and friendship but more importantly on space for individuality. I've been fortunate to experience a relationship like that with both my parents, and today, I want to share about my father, Naazir Mahmood, in honour of his 60th birthday. In the three decades of my life, I’ve seen my father as a funny man, a kind man, a progressive man, and a man who cherishes the company of his friends and family above all else. Born on 17th June 1964 in Karachi to a middle-class family, my father spent his younger years helping his father and three brothers in a glasswork business after attending classes at a government college. While his siblings set up their own businesses into reaching adulthood, my father decided that was not his calling and he embarked on a professional career at an advertising agency. This marked the start of an interesting journey that would lead him from journalism to heading a prestigious higher education institute in Karachi. However, my aim is not to highlight his career trajectory, but to focus on his interests outside work, the kind of person he is, and what he means to his family and friends.

My father’s second love is that of movies. Growing up watching them in his company, the likes of Charlie Chaplin and classics of Italy’s neorealistic cinema, my sisters and I learned to appreciate films not just as entertainment but as nuanced works of art

As an avid reader, an academic and a movie-buff, my father has always embraced life actively, rather than passively. Raised on the importance of loving literature and art by my grandfather, I always saw Abba include time for reading and intellectual engagement in his daily routine. As a devoted leftist and a fundamentally secular man, he has been one of the few voices who has advocated for liberal policies in Pakistan through his writings in various newspapers. Those who frequent our house in Islamabad know that his basement library is Abba’s favourite spot; a corner which houses thousands of books on every subject under the sun. In fact, there's a running joke in the family about the multiple master's degrees he has completed—perhaps one for each decade of his life - ranging from English literature to Islamic studies. My father’s second love is that of movies. Growing up watching them in his company, the likes of Charlie Chaplin and classics of Italy’s neorealistic cinema, my sisters and I learned to appreciate films not just as entertainment but as nuanced works of art. Now that I'm older, I can't help but watch movies with a critical eye —able to discern when a screenplay needs to pick up the pace or when it has been executed with precision.

Yet, for my father, living actively has meant not just engaging in diverse interests but also maintaining a presence for loved ones. Often sacrificing his own time and resources, he has not hesitated to drop everything to ensure his friends and family members are supported. During a recent visit to Karachi from Islamabad to visit my ailing grandfather, I had the chance to observe his unwavering presence for his own father. Abba spent nights caring for my daada, engaging him in conversations, reciting poetry, and watching YouTube videos about the streets of Bombay, the birthplace of my grandfather. The same love and attentiveness have been the cornerstone in his approach towards parenting. Despite never placing much importance on material things, his priorities for my sisters and I have been to enrich our life through travel and he provided us with the financial support to pursue education abroad.

Having lived a few good years studying in Russia during the 1980s Soviet era, and later obtaining a scholarship to study in the UK, his second move gave my siblings and I the opportunity to experience schooling abroad and make friends from many different countries. Despite these moves across countries or perhaps because of them, one of the most intimate lessons I learned from Abba is his deep love for Pakistan and a strong sense of being rooted to the country. On occasionally asking why he chose not to obtain foreign nationality while pursuing his PhD in the UK, his steadfast response has always been, “If I have to face challenges wherever I go in the world, I may as well do so in my own country.”

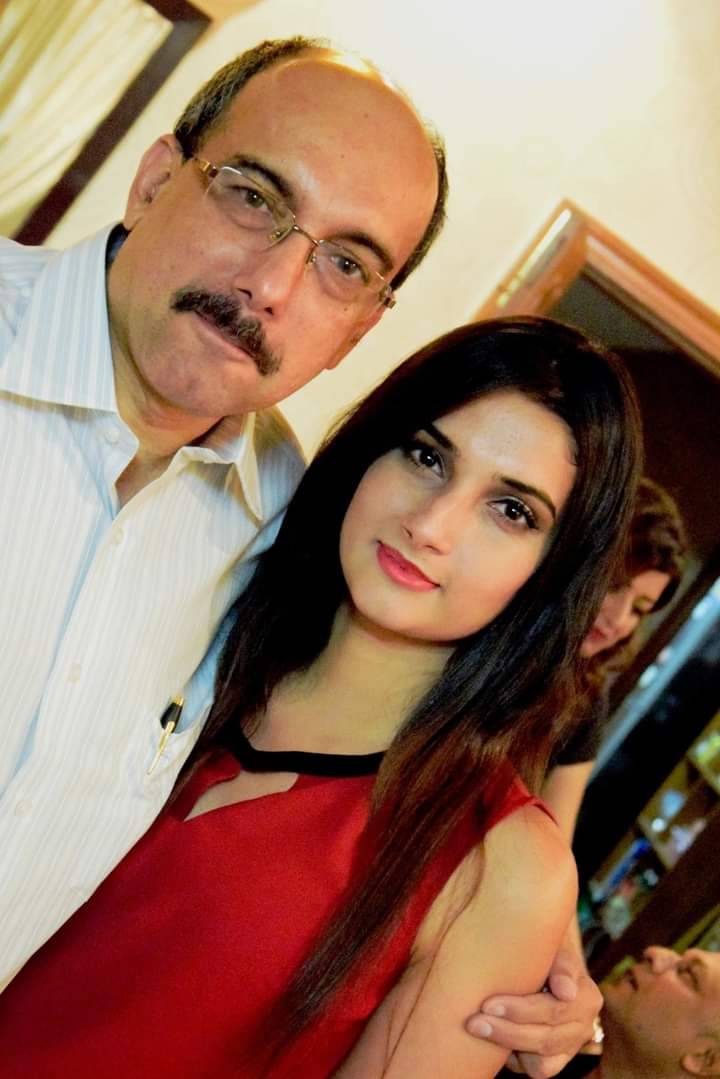

Going through old family photos and seeing pictures of my father with his friends in his twenties, my parents’ early days of marriage and dog-eared advertisements of the ad agency he worked with in his early career, I was reminded of a quote from an article in the New Yorker “it can be a twentysomething rite of passage to realise that your parents are more than your parents; that they had a life before you; that they were beautiful and moved beautifully and were desired, and still are.”

I often feel that in a patriarchal society, the best ally a woman can have is her father, and what I am most proud of in mine is that he has never shied away from identifying as a feminist. As a father to three young women, he has modelled positive masculinity in both words and actions and as I continue on my own path, I carry with me the lessons and values that he has imparted.