Widely considered to be the father of modern Chinese literature, Lu Xun – born 140 years ago today – was also the founder of the League of Left-Wing Writers, the editor of several left publications, including New Youth, and an early supporter of the Esperanto movement in China. Although the communists have historically claimed him as one of their own, he was never a member of the party. In fact, Chairman Mao Zedong posthumously conferred on him the membership of the Communist Party of China (CPC). uring his own brief and stormy life, Lu Xun wrote short stories, poetry and hundreds of essays, and he was the most prominent thinker to emerge out of the historic May the Fourth Movement of 1919, which released political, intellectual and creative energies which eventually led to the creation of the CPC a couple of years later and after their victory over the Nationalist forces led by Chiang Kai-Shek, the Maoist Revolution three decades later.

A look at some of Lu Xun’s contemporaries across the world mark him out to be in distinguished company: Rabindranath Tagore, Muhammad Iqbal and Munshi Premchand in our own South Asian Subcontinent; José Martí in Cuba; the great Italian communist Antonio Gramsci in Italy; and the founder of the first socialist state, the Russian Vladimir Lenin.

I believe Lu could have been the first Chinese writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature based on just the three slim volumes of his fiction – notwithstanding his distinguished stature in poetry and essays – but his engagement with the CPC in his final years put paid to that hope. Instead, the Chinese had to wait for almost eight decades to have their first homegrown Nobel laureate in literature!

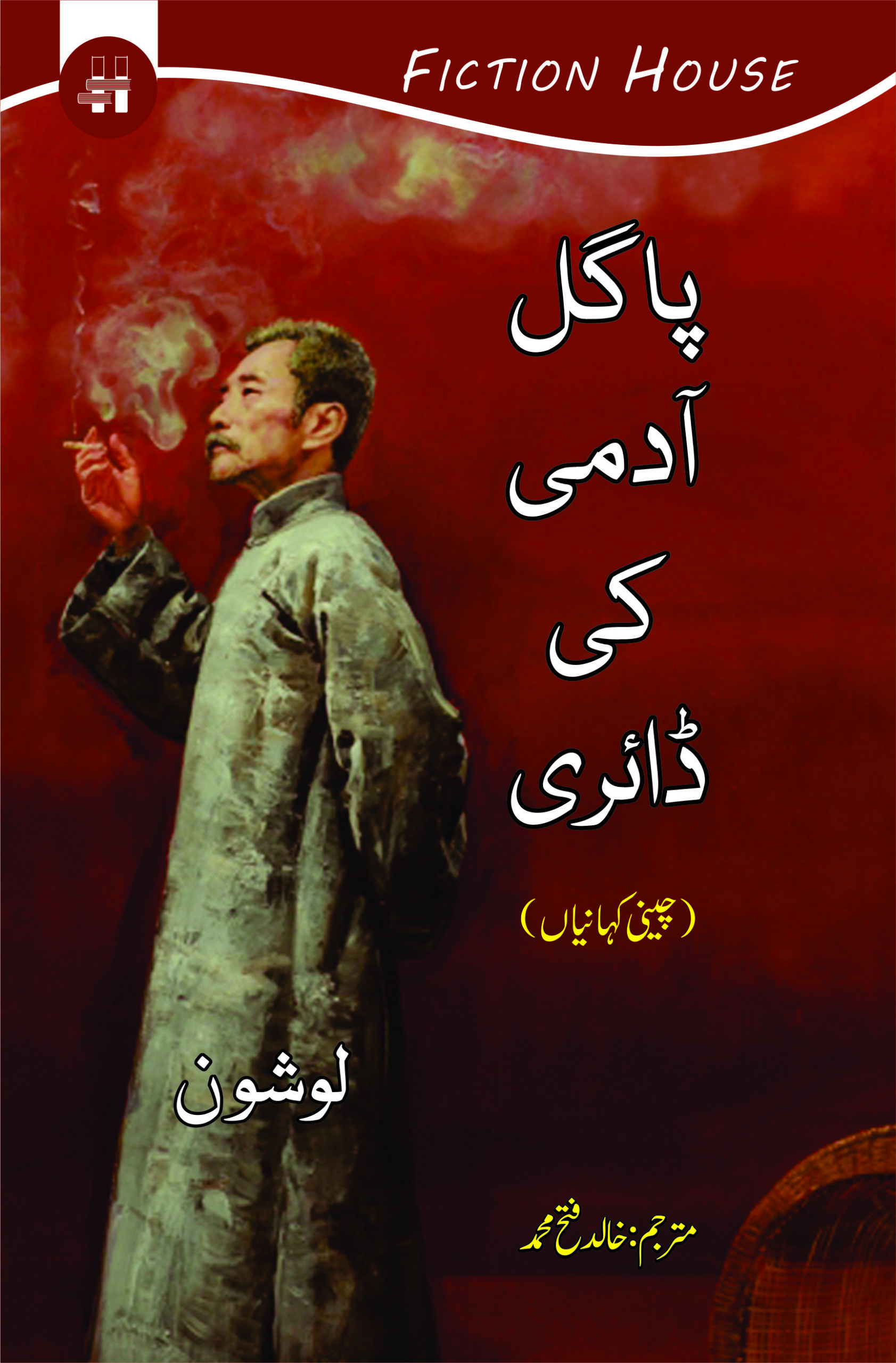

2021 marks the centenary year of the foundation of the CPC and it is here that a volume of translations in Urdu of Lu Xun’s selected stories feels welcome. While the work of Lu Xun has been translated and re-translated multiple times into English and other major languages, given his stature in Chinese letters; the same cannot be said of Urdu

However, unlike Tagore, Iqbal and Premchand, Lu Xun could never be fully canonized in modern China, which is as true of the 21st century as the last one, despite effusive praise from Mao Zedong. Instead, the ancient thinker Confucius was – and continues to be - championed far more by the Chinese revolutionary state.

Over here in Pakistan, with its much-vaunted history of China-Pakistan relations, we have never familiarized ourselves with any significant elements of Chinese culture and literature - except a very rudimentary familiarity with the Chinese language, what with the multiplicity of Confucius Institutes opening up all over the country. The discourse around China in the highest policy circles unfortunately still revolves around the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) while on the Left, we seldom go beyond the cliché that the greatest poverty-alleviation experiment in the twentieth century happened in Maoist China, to which – rightly – has now been added the achievement of successfully combatting the COVID – 19 outbreak, which was detected relatively late in Wuhan; making China one of the first countries to successfully recover from the pandemic and open up the country for its citizens and the world alike.

2021 marks the centenary year of the foundation of the CPC and it is here that a volume of translations in Urdu of Lu Xun’s selected stories feels welcome. While the work of Lu Xun has been translated and re-translated multiple times into English and other major languages, given his stature in Chinese letters; the same cannot be said of Urdu. Indeed it is a great pity that the translation of China’s greatest modern writer – or for any major Chinese writer for that matter – has been so late in coming. Be that as it may, the translations under review have been done by senior and prolific fiction writer and translator Khalid Fateh Muhammad from the English.

Title: Pagal Aadmi Ki Diary (Chinese Stories)

Written by: Lu Xun

Translated by: Khalid Fateh Muhammad

Publisher: FICTION HOUSE, Lahore

ISBN: 9789695627846

Pages: 112pp.

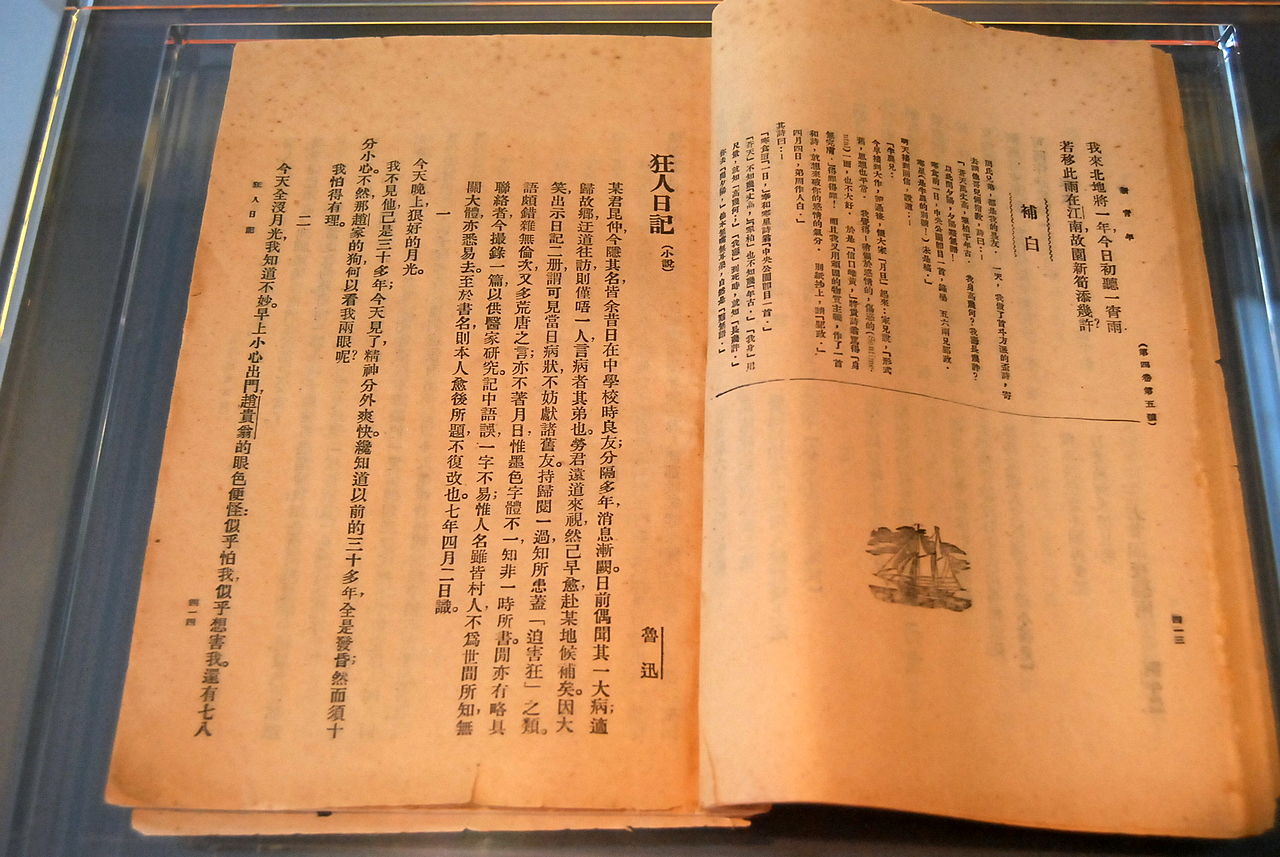

There are five stories included in this brief volume, including the eponymous Diary of A Madman, which was inspired by Gogol, with its comparison of Chinese feudal society to cannibalism; it became one of the representative works of the anti-Confucian New Culture Movement, which called for the creation of a new Chinese culture and society, based on democracy and science. In fact the themes which run through all the 5 stories translated in this volume are all those which were the hallmark of the whole of Lu Xun’s oeuvre: anti-Confucianism with its respect for authority, traditional family values, respect for the dead and organized religion; against feudalism and imperialism.

In the first story Pagal Aadmi Ki Diary, the protagonist is a madman who is the only one who can clearly see how his fellow villagers are allegedly going cannibalistic. The madman had dared to see the old accounts of a certain Mr Ku Chiu and following this, to the former, everyone appears bent on eating him, including members of his own family. The madman is actually a literary device to criticize Confucian teachings; indeed mention is made of them when the madman in his attempts to understand this descent into cannibalism refers to the Confucian classics replete with the words “Virtue and Morality” and “Eat People”. Here the resort to cannibalism and the reference to the Confucian classics signified Lu Xun’s biting critique of centuries-old tradition in thrall to Confucian mores which had corrupted the Chinese psyche and reduced them to being servile and humiliated.

However like a great realist, Lu Xun does not suffice only with diagnosing the ills but ends the story with a famous line, investing his hopes in the younger generation who have not been so corrupted: “Perhaps there are still a few children which have not been eaten by Man. Save the children.”

The second story Chaara (Fodder) better known in English as “Gathering Vetch” is a story of two ageing brothers who were residing in an old-age home and following the conquest of their father’s kingdom by a rival, refused to eat anything of their rival’s food out of loyalty to the former king; so much so that they resolve to leave the home and pass their final days living on a mountain subsisting on berries and leaves.

Fateh Muhammad should have explained not only his criteria for selecting these particular stories but also his process of translation itself in the all-too-brief introduction at the beginning of the volume

Lu Xun criticizes the centuries-old Confucian teachings which will force a man to respect authority and his forebears so much so that rather than find work to change their lot, the brothers embark on an impractical journey which will make them dependent on the vagaries of nature, citing the adage, “Heaven is unbiased, but often supports goodness.” Even the wayfarers who seek to rob the two brothers invoke the traditional respect to the elderly, but then proceed to search the two – even after being told that there was nothing on them!

The two brothers do succeed in reaching the mountain and subsisting on whatever they could find by way of vetches, until they exhaust the available supply. Then one day, a maid chances upon them eating ‘lunch’ and after finding out their rationale for doing so, mocks them, saying, “The entire land under the heavens is the property of our king. The vetches which you are eating, is that not the property of our king?”

Upon hearing this taunt, which was made in jest, the two brothers stopped eating, and eventually starved to death on the mountain.

Towards the end of his life, just a year before he passed away, Lu Xun broke his self-imposed exile from writing short stories and published his final short story collection, where he re-interpreted ancient Chinese myths and legends to satirize the oppressive conditions under Chiang Kai-shek; three of these fables are included in the work under review: the aforementioned Chaara, Darre Se Ravaangi (Leaving the Pass) and Sailaab (Curbing the Flood).

However, without the necessary perspective on ancient Chinese history, even the well-intentioned reader would not be able to understand why the writer wrote these stories in the first place, hence one is confounded as to the translator’s criteria in selecting the latter two stories for this volume. Nevertheless, one can summarize the latter two stories as a devastating lampoon on Laozi (Lao Tzu), the philosopher of the Taoist school; and the reactionary scholars spawned by the Chiang Kai-shek regime.

I personally enjoyed the story Beva ka Beta (The Widow’s Son) from this collection, where the writer gives the disclaimer at the very beginning that "This is such a story of a widow’s son which ends in two ways." Suffice it to say that the two ways in which Lu Xun ends the story go back to the main theme running in all of his fiction - as to whether art should be for life’s sake or for art’s sake? I personally found the second ending more satisfying and convincing, but without giving anything away, readers may have their own preference.

A note on the translation. Based on comparing just one passage from the title story in both the English and Urdu versions, one notes that whole words and sentences have been taken out or added to the original text. This, in my humble view as a translator, does credit to neither the author nor the translator, in fact, by privileging the translator’s version over the voice of the writer himself, it muzzles the latter. And Fateh Muhammad should have explained not only his criteria for selecting these particular stories but also his process of translation itself in the all-too-brief introduction at the beginning of the volume, not only for understanding his own craft but also by way of guidance for budding and inexperienced translators.

Also, the volume is dotted with proofing errors, which significantly mars the reading pleasure of the reader, given that something is already lost in translation when one picks up the volume. This is not expected from a publisher like Fiction House, which has been around for a while now and is reputed for publishing several important texts in Urdu translation over the years.

Despite these problems, to be able to read Lu Xun’s path-breaking fiction in Urdu on the occasions of his 140th birthday and the centenary of the foundation of the CPC this year is a liberating experience and one hopes to see more translations in Urdu of the work of the man who practically defined Chinese culture in the 20th century and foresaw the bleakness of the present.

Note: All translations are by the writer.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist and award-winning translator and dramatic reader based in Lahore, where he is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association. He is currently working on a book Sahir Ludhianvi’s Lahore, Lahore’s Sahir Ludhianvi, forthcoming in 2021. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com