What were the most important intellectual influences on you, growing up in the 80s? Which thinkers informed your view of South Asian and global history?

What were the most important intellectual influences on you, growing up in the 80s? Which thinkers informed your view of South Asian and global history?Ayesha Jalal, Dr. Mubarak Ali and K.K. Aziz. You must remember that in the 1980s I was in college and posing to be a Marxist. I was expected to be reading all the usual leftist literature, which I did. But I wasn’t entirely satisfied. I wanted to understand what was going so wrong in Pakistan. It was easier to understand how the Zia-ul-Haq regime was retarding the country’s political and social evolution, but it was quite apparent that this wasn’t being done in a sudden vacuum.

This is when I stumbled upon K.K. Aziz’s ‘Murder of History’, which was first published in 1985. This book, along with Sibt-e-Hassan’s ‘Battle of Ideas in Pakistan’, opened up a whole new can of worms for me. This was the first time I was made to realise that the the roots of Pakistan’s ideological predicaments lay way back; not only to the time of the country’s creation in 1947, but even before that - soon after the complete demise of the Mughal Empire in India.

‘If the supremely pragmatic Chinese want to invest in Pakistan on such a scale, Pakistan is going nowhere but up’

It was a fascinating realisation for a teen who, till then, had known more about China, the Soviet Union and Cuba than his own country. I mean, knowing Pakistan through official history text books was like understanding the region’s history through Nasim Hijazi novels! So here is where folk like Jalal, Mubarak Ali and Aziz came in. At the time they had just begun to comment on the more hidden aspects of the country’s past, but that was enough for a young man like me to realise how we had been lied to. The feeling was one of outrage but also of empowerment. It was a wonderful feeling, really. I then naturally moved on to reading Eqbal Ahmad and Hamza Alavi. I even managed to get a copy of Stanley Wolpert’s book on Jinnah which was banned by the Zia regime.

When, 50 years from now, the social and cultural history of Pakistan is written from a long-term perspective, what place do you think the late 1970s and 80s would have in such a story? Would it be purely a tale of repression and of a cultural black hole? Did this period have any redeeming aspects, in your view?

The era cannot be forgotten. Indeed it was bleak and all, but it needs to be studied deeply because in it are clues to understanding what transpired in Pakistan in the shape of extremism and sectarian violence after Zia’s demise in 1988. 50 years from now, that era might be studied as a way to determine what not to do in a diverse but volatile region such as Pakistan. It can teach us how not to use religion as a political tool and experiment to concoct a synthetic idea of a national whole in a region rich in ethnic and religious diversities. The attempt to achieve this began in the 1950s, but it reached a crescendo in the 1980s. The results were disastrous. This is what is to be learned from that era.

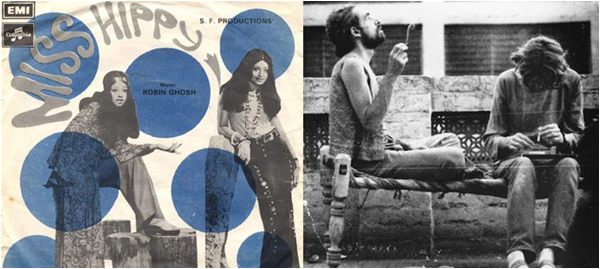

One gets the impression of a certain degree of nostalgia from your Smokers’ Corner articles in Dawn. Was Karachi of the 1960s and 70s truly this happening, swinging place before the state began enforcing conservatism? What was life like for a young middle-class urban Karachiite back in the day?

I was merely a child in the 1970s. But even as a child I remember things were very different compared to what became of the country when I entered my teens in the 1980s. Compared to the state of society from the 1980s onward, one can safely suggest that, indeed, till the late 1970s we were evolving quite naturally as any normal developing country would.

Yes, there was political turmoil, economic downturns, and all, but our evolution as a society was largely organic in nature. This evolution got retarded somewhere along the line. As I have detailed in my book, many factors fuelled this retardation. There was the decision of the Z.A. Bhutto regime to use populist politics and a bit of religion to attempt social engineering after the separation of East Pakistan; and then how such an attempt was given a more authoritarian dimension - sans the populism - by the Zia dictatorship; and how we are still struggling to wriggle our way out of the social cobwebs weaved by such experiments. The fact that so many Pakistanis began to travel to oil-rich Arab countries from the late 1970s onward also contributed. There, many Pakistanis came into contact with a strand of Islam that was almost entirely alien to the strand of the faith which had indigenously evolved in South Asia. This also played a major role in retarding the organic evolution of society.

As to what life was like for the urban middle-classes in the 1970s, well, I would say, it was less complicated, more open and enterprising and far less judgmental, or for that matter, not quite as paranoid as it has become today.

However, the irony is: today the middle-classes have grown in power and influence. They are in a transnational stage and thus, in a flux. They have exhausted the religious aspects of the ideology they were indoctrinated with in the last 30 years to define their identities. So it is going to be interesting now to see what comes next from them once they do make that final transition from once being a neglected minority to becoming influential economic and political players. This is already happening.

In the book, you seem to trace religious obscurantism to the Muslim revivalist and reformist movements of the colonial period. What direction do you think South Asian Muslim politics and culture might have taken if these movements had not existed?

These movements were bound to emerge. Had the British not arrived, or the Mughal Empire hadn’t collapsed, only then can one contemplate what might have happened in the region without the presence of these movements. But history is the greatest of shapers. The British understood this, the Mughals didn’t. Muslim reformists like Sir Syed and then Jinnah understood this, but their opponents, such as the obscurantist Muslims, didn’t. So it is ironic to note that eventually, in Pakistan, ideas of those who understood the shaping and reshaping powers of history, faded away, replaced by the ideas of those who didn’t. That is why on so many occasions we have found ourselves lingering on the wrong sides of history. This is an entirely bad thing. One does not fight against the tide of history. One learns from history and uses it for their own benefit. But if you go against it, the tide will destroy you. You will drown.

You conclude your book End of the Past by emphasising the pragmatism of Mr. Jinnah. You seem to suggest that Pakistan could find a way out of its current storm of religious and ethnic violence by rediscovering Jinnah’s pragmatism. Do you not feel that at least some of the difficulties faced by Pakistan (in becoming a pluralistic Muslim state) have their roots in Mr. Jinnah’s pragmatism itself? After all, this was a pragmatism which was comfortable in employing Muslim communalism and religious-conservatism as much as “secularism”, depending on the needs of the All-India Muslim League at any given moment?

Pragmatism is not an ideology, as such. Jinnah was a politician, nothing more, nothing less. A brilliant politician, mind you. He had to be pragmatic. All politics is pragmatic. He was the man of the moment. Thus, had he even lived for, say, another ten years or so after Pakistan’s creation, the moment to him would have determined his actions. What I mean to say is that, the moment was a country struggling to justify its sudden existence and was populated by a diverse number of ethnicities, Islamic sects, sub-sects and some other religions. What would Jinnah the pragmatist have done? He most certainly would not have sanctioned the authoring of something like the 1949 Objectives Resolution. His pragmatism would not have allowed this. He was not an ideologue. But after his demise, we went looking for ideologues, who in turn transformed Jinnah’s memory and image into that of an ideologue. And here lay the problem. We needed to be pragmatic. We chose to be ideological. And then we concocted an ideology and tried to enforce it upon a diverse population. And anyway, the creation of this ideology was not consensual. It was not democratic. It became a tool. A destructive weapon. Some of us are still trying to air it. We need to be pragmatic. Pakistan survived, it’s here. We do not have to justify its existence anymore. We have to turn it into a strong, confident entity. We need to be pragmatic and rational about it, not reactive.

There is a view among some harsh critics that the Pakistan project was fated to its current situation from the very beginning. Do you sometimes fear that this might be history’s eventual verdict on Pakistani history? Could we conceivably have gone in a different direction, and if so, what was the most critical fork-in-the-road for Pakistan?

As I said, Pakistan survived. It will survive. Now too many people’s economic survival and well being is attached to its existence. Pakistan’s disintegration is not a threat anymore. Economic interests of the kind I have mentioned will make sure of that. The CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor) is a great example. The Chinese are supremely pragmatic. They always have been. If they want to invest in Pakistan on such a large scale, then rest assured, Pakistan is going nowhere, but up. This is not an overtly optimistic assessment. It’s a pragmatic observation. But we just need to keep ourselves on the right side of history. The fork-in-the-road moments have all been about decisions which threw us on history’s wrong side.

There will always be those who associate you with your writing from the ‘1990s on music. Do you feel that contemporary Pakistani music is at all worth writing about?

The truth is that I have no clue about the current music scene. I believe there really hasn’t been one for over a decade now. But there should be. We are quite good at it. Nevertheless, even at the height of the local pop scene in the 1990s, there was a feeling that it was almost entirely being navigated by corporate sponsors. And there is nothing wrong with that, as such. But the problem was that the multinationals were investing in the artistes, not in the scene. So the so-called scene remained largely synthetic. Thus, once multinational interest shifted from music, the scene simply eroded. It was never an organic, self-sufficient scene. Then, of course, the extremist violence that erupted in the country from the early 2000s didn’t help either. Concerts came to a halt. And without much corporate money in the scene, artistes didn’t quite know how to sustain themselves anymore. But still there have been success stories. Ali Zafar is one. Atif Aslam is another. And then the whole Coke Studio thing, which I believe was a brilliant idea and still is.

A funny thing happened last year. I was asked a question by a BBC reporter about Coke Studio, and I praised it. When the interview was aired, I got a few emails by some well meaning young men who asked how could I praise Coke Studio when, in the 1990s, I had scorned at corporate sponsorship in music. “We thought you still supported underground bands” they lamented. Well, first of all, I was against corporate investment in individuals only and advised that investment should actually go in the scene. Secondly, how can there be an underground scene when today even a so-called mainstream scene is struggling to survive? Nevertheless, underground, overground, digital, analogue, whatever the local music scene is up to these days, it should be encouraged and best of luck to the artistes.

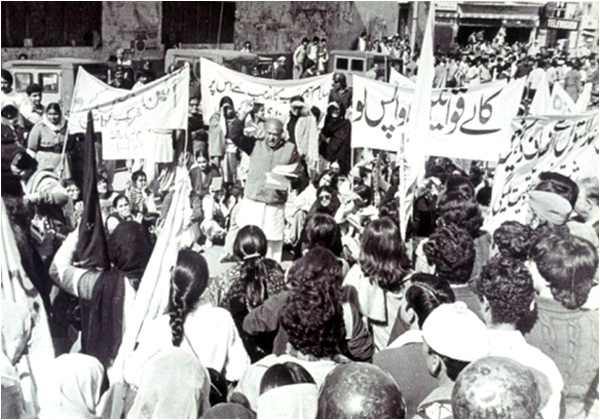

You write about the rise of the National Awami Party (NAP) in your book. Would you agree with the view that this was a motley collection of various suppressed nationalists which was doomed to eventual implosion? Do you think NAP could have ever become a serious rival to the PPP?

Yes, it was a collection. But a noble one. The left was fragmented due to what I call secular sectarianism. Maoists, Trotskyites, Leninists ... this, that. NAP at least had the good sense to get folk from all shades of progressive politics together. However, it was this secular sectarianism of the left which triggered the implosion of NAP too. This happened due to the Sino-Soviet split. Had the split not happened and NAP had remained intact, I believe it could have been a major hindrance to the rise of the PPP. NAP was the first major experiment of the left in Pakistan. It’s unfortunate that not much is written about it. When the left is discussed, it’s always about the Communist Party of Pakistan, whose memory and role is always entirely overrated by historians, or the PPP, which was always more populist than leftist.

‘There is much beauty and history to be seen in Pakistan but it can't always be enjoyed entirely with tea or lassi’

In your book, you speak at some length about the factors that gave rise to the politics of the MQM. What future do you see for Mohajir identity-based politics, given recent developments?

The politics of Mohair identity will get even more pronounced. The Pashtuns are now the second largest community in Karachi. The MQM is thus falling back on its original goal of shaping Mohajir nationalism. This nationalism is now as strong as it was twenty years ago. It has never been as well developed as, say, Sindhi, Pashtun or Baloch nationalism, but its evolution is still an on-going process. The MQM is the main architect of Mohajir nationalism. Interestingly, though, like Sindhi, Pushtun and Baloch nationalisms, Mohajir nationalism too is secular. However, unlike the nationalisms of its ethnic counterparts, it does not have a history of also incorporating leftist ideas. Mohajir nationalism is entirely urbane, secular and an enthusiastic supporter of capitalist development models. It’s here to stay, at least in Karachi, a city where such a metropolitan, capitalist and inherently secular outlook prevails due to the economic dynamics and history of the city.

Today there is a prevailing sense of optimism amongst some Pakistani analysts that a crucial ‘consensus’ is finally emerging around the issue of religious fundamentalism, and that this bodes well for us. There are even those who suggest we finally “have our basics in order”. Do you think that the worst is behind us as a country?

Yes. But it is a cautious ‘yes’. It’s a start. An important start which, if handled sensibly and at the same time boldly, may just go on to place Pakistan on the right side of history. So kudos to General Raheel Sharif, the military, the sitting government and the parliament for taking this initiative. Of course, one is justified to lament that we as a nation and state had to see the brutal demise of thousands of innocent civilians, soldiers and politicians to finally take this initiative, but a consensus was finally achieved. It’s an existential crisis. And the initiative is a pragmatic one. This is sensible. But there’s a long way to go. No matter who the next army chief is, or who forms the next government, this process should not be tampered with. It should remain a constant. It is vital that it does.

What would your verdict be on Bhutto’s mix of nationalism, socialism and Islam? Do you think he ended up reinforcing authoritarianism at the end of the day, and could his PPP have taken a different trajectory?

As I have mentioned in my book, I firmly believe Bhutto, at some point in the mid-1970s, noticed a revival of interest in religion taking place in Muslim countries, and wanted to tap into it before his opponents on the right could. Well, he kind of did, but uncannily ended up empowering the rightists because they were the ones who were still shaping the religious narrative through the mosque and the right-wing Urdu media. Bhutto was a great student of history. He saw a historical trend taking shape after the way the oil-rich conservative Arab monarchies became hugely influential at the end of the 1973 Egypt-Israel War. But what he missed out on was that these monarchies and the United States were also cozying up to the religious parties who were overtly anti-Soviet. It is through this loophole that these parties slipped in and then so did Zia. Bhutto was left out to dry. In trying to capture a historical trend, he was run-over by it. He became careless.

What do you think progressive politics ought to look like in today’s Pakistan? Do you see any space for that sort of thing in contemporary Pakistan, or should liberals and leftists make their peace with the PTI?

Poor PTI, it’s not bad is it? But seriously, there is still a lot of scope for progressive politics in this country. But, of course, ideological concepts in the post-Cold-War world have been changing so rapidly - one has to be careful to not sounding archaic while describing things like progressivism, liberalism, conservatism, religious fundamentalism, the left, the right ...

Simply put, liberalism is the new left. The conventional left just continues to operate in a delusional vacuum, sometimes ending up siding with certain reactionary forces purely out of desperation. I can understand its predicament. But I can’t sympathise with it. It’s a fringe now and is behaving like one. Funny thing is: a lot of its rhetoric has already been hijacked by certain populist rightist groups.

So what is progressivism today, especially in the context of Pakistan? Let me give you an example. Recently I supported those who vehemently criticised some men and women who have made it a habit of bashing Malala for shameless cynical purposes - such as achieving TV ratings; or to channelise some unaddressed psychological issues lingering in them which somehow sees them actually being threatened by the rising public profile of a school girl who was shot in the face and had to leave the country.

But at the same time I was publicly appreciative of the recently held education and book fair organised by the Jamat-I-Islami and its student wing in Karachi.

The thing is, progressivism is never about a knee-jerk attitude. The book fair by JI was an admirable initiative. But at the same time, progressivism also demands that one should question the limits of things like freedom of speech which, ironically, in this day and age, is mostly being exploited by those on the right who actually hate it but use it the most.

Constantly attacking an intelligent schoolgirl who has won a Nobel Prize, makes us seem like nuts! A majority of Pakistanis are not nuts. So why let utter nuts define our mindset? Grown-up men and women on TV do this. Should idiots like these be given the right to air their nonsense on national television? No. They are against the interests of Pakistan. We are embroiled in an existential battle, and they come dismissively waving a book on the girl, or worse, turn Valentine’s Day into an actual national issue! The mind boggles.

About PTI, it is still evolving. I personally think Imran is evolving too, but, yes, at times, he comes up with something so absurd that you begin to think: what on earth happened there?

I mean, at one point he will not be afraid to scathingly comment on sectarian outfits, then, while visiting the parents of school kids downed by militants, he will advise opening offices for the militants. Are we missing something here?

His rallies have been the epitome of social and lifestyle liberalism with a very encouraging participation of women, and yet, I’ve always found him hesitating to rein in some extremely uncouth PTI men from making entirely reactionary and sexist comments in the media.

Khan is still very much an enigma. Very ad hoc. But I remain a fan.

One recalls that you were quite critical of the lawyers and students protesting against General Pervez Musharraf’s rule. For you, what should a true democrat have done in the Musharraf era?

A true democrat should have been able to see through the facade of the the gallant judge and also tried to eject certain clearly reactionary forces who had begun to navigate the discourse of the lawyers’ movement.

What prospects, if any, do you see for a revival of the PPP outside Sindh?

With Bilawal now at the helm, I believe the PPP can revive itself outside Sindh in the next ten years or so. But Bilawal has to first make sure that the nature of his dad’s politics in Sindh doesn’t eventually end up eroding the party’s influence in Sindh as well. Bilawal is a well-meaning and sharp lad. But he has to become Bilawal first, instead of his granddad or his mother. Bilawal has to become his own man.

Your book contains amusing anecdotes about run-ins with the Zia-era police over various substances. Are Pakistan’s drinkers consigned to the shadows forever, or could the circumstances ever arise for some relaxation from the state on alcohol?

As I mentioned in the book, alcohol is not such an issue anymore in Pakistan. But I do see some form of relaxation returning in the coming decades, because if the country’s current economic ambitions finally bear fruit, with economic prosperity and foreign investment would come stability. With stability shall come foreign businessmen. They are likely to be followed by tourists. And though there is so much beauty and history to be seen in Pakistan, it can’t always be enjoyed entirely with a cup of tea or a glass of lassi.

The rest of the country should learn from Karachi. Alcoholic beverages are easily available here, but no one makes such a hue and cry. Those who drink, largely enjoy it in a pleasant manner, and those who don’t, no one forces them to.

In certain situations, Karachi is certainly a very live and let live city. Cheers!

Ziyad Faisal may be reached at ziyadfaisal@gmail.com