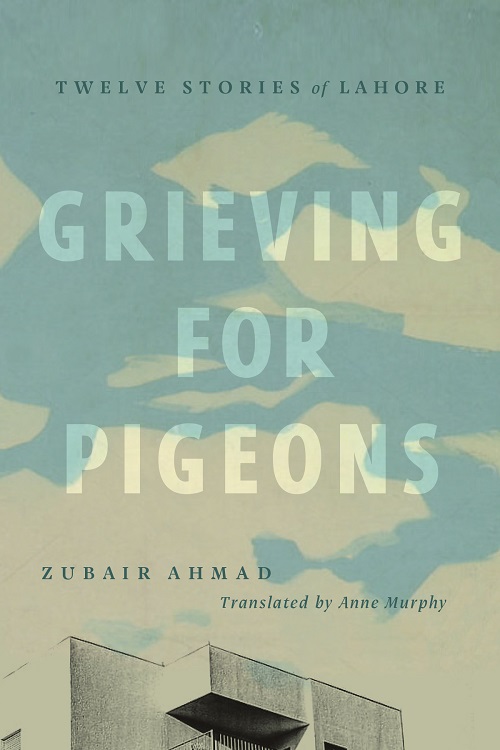

Grieving for the Pigeons is a collection of twelve stories selected from the three books of Zubair Ahmad ‘s short stories – a renowned Punjabi literature writer. It is translated by Dr Anne Murphy, an Associate Professor of History at the University of British Columbia, in Canada. The book is published by Athabasca University Press and Readings in Pakistan.

Mr. Ahmad, a former professor of English literature, a son of the soil, chose his mother tongue as a medium of creative expression. He has heartedly contributed in the depiction of cultural and historical heritage of Lahore and has empowered the Punjabi language in his writings. He has worked hard throughout his life for the promotion and image-building of the Punjabi language. He has published two poetry and three short story books. Ahmad’s love and passion for his mother tongue is acknowledged all over the world for which he was awarded the Dahan International Punjabi Prize for his short stories “Kabootar, banere te galliyaan” and “Paani di kandh” in 2013 and 2022 respectively.

Ahmad’s writing attracted the attention of readers not only in South Asia but in Canada as well. Dr Anne Murphy, being a cultural historian, was inspired by the beauty of Punjab’s literature, its people and its vibrant art. She came to Lahore in 2014, where she met Zubair Ahmad, and was instantly spellbound by his writing. Experiencing the rich and warm heritage of Lahore, she was convinced by the saying:

“Until one has seen Lahore, they have not been born”

She says, “My visit had a magical effect on me in 2014. The idea of translating stories was born during this visit.”

It is not an easy task to translate the short stories of Ahmad, who captures the lives and experiences of the people of Punjab in an intimate narrative style. The stories evoke the complex realities of post-colonial Pakistani Punjab. The narrator dives in the depths of his subconscious, shifting between past and present, recalling the different eras of Lahore, its neighbourhoods and the communities that defined them.

Dr Murphy’s research focusing on the vernacular literary and religious traditions of Punjab proved her devotion. The book Grieving for the Pigeons invites us into a world of remembrance. It is a difficult task for the translator to convert creative expressions into a different language that relates to the entire world.

Ahmad says, “I have no hesitation in saying that my stories are based on reality and lifelong experiences while keeping the fiction intact expressing the bitter truths of society in remarkable tone and influential words.”

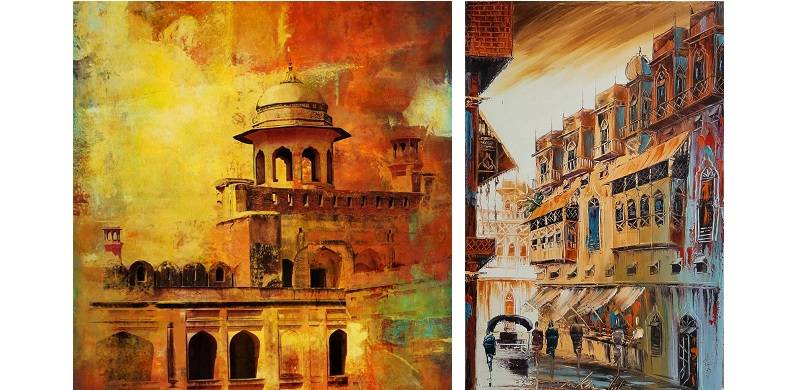

Lahore has a perceptible presence in the short stories. Its roads, cafes, landmarks and history spellbind the readers. The book is a tornado of thoughts. Walking through the narrow lanes of the old Anarkali in front of the masses, around Mall Road, along with the rallies and protests. We are introduced to Gol Baagh and Laat Sahab, and all of a sudden we wander in the streets of Rome and again return back to the muddy streets of Krishan Nagar where the author spent his childhood to youth.

The narrative revolves around the framework of past, present and future. We see many layers under the complex circumstances. For example, we find the same situation in T. S. Elliot’s poem,

“Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past

If all time is eternally present”

A man sitting in his Krishan Nagar home and seeing at once Lahore, Rome and Batala, he flies in 1947 with the trauma of Partition that shattered the Punjab region and slips down to the 1970s. The slippage between past and present reminds us that time knows no boundaries and no lanes in the mind of a creative writer.

For Dr Anne Murphy, this is her first book-length translation. It is her keen observation and love for history and culture that produced such a masterpiece. She has helped people to understand the obligations of reciprocation and its consequences.

“Pigeons, Ledges and Streets” is narrated in an artistic, cultural and historical way. Dr Murphy tends to depict the characters the same as in the actual story. In “Walli Ullah is lost,” the character of Altaf is portrayed sarcastically.

“Mr. Altaf would not move a muscle, nor would he allow the boys to move away.”

Gamay of “Pigeons, Ledges and Streets,” Naseem of “Rain,” Bajwa, Walliullah and Bali have a realistic flow within the content of the story. Reading them shows us that they are painted with the same creative brush but in different domains.

Dr Murphy has made a successful effort to recognise the culture and heritage of a dynamic city like Lahore in “The Estranged City.”

The last story “Paani di Kandh” is translated by Dr Murphy as “Wall of Water.” It relates the visit of the author to Batala in 2005 in search of his parents’ home. It is a complex story to reach what his parents left in the wake of a bloody partition, and a reunion with his past. The remains of his uncle whispered to him “You have come after sixty years to give me a shroud.”

Dr Murphy uses his own words to profoundly enhance the psychological feelings of the author. A truly appreciable effort that will definitely attract a lot of readers.

Mr. Ahmad, a former professor of English literature, a son of the soil, chose his mother tongue as a medium of creative expression. He has heartedly contributed in the depiction of cultural and historical heritage of Lahore and has empowered the Punjabi language in his writings. He has worked hard throughout his life for the promotion and image-building of the Punjabi language. He has published two poetry and three short story books. Ahmad’s love and passion for his mother tongue is acknowledged all over the world for which he was awarded the Dahan International Punjabi Prize for his short stories “Kabootar, banere te galliyaan” and “Paani di kandh” in 2013 and 2022 respectively.

Ahmad’s writing attracted the attention of readers not only in South Asia but in Canada as well. Dr Anne Murphy, being a cultural historian, was inspired by the beauty of Punjab’s literature, its people and its vibrant art. She came to Lahore in 2014, where she met Zubair Ahmad, and was instantly spellbound by his writing. Experiencing the rich and warm heritage of Lahore, she was convinced by the saying:

“Until one has seen Lahore, they have not been born”

She says, “My visit had a magical effect on me in 2014. The idea of translating stories was born during this visit.”

It is not an easy task to translate the short stories of Ahmad, who captures the lives and experiences of the people of Punjab in an intimate narrative style. The stories evoke the complex realities of post-colonial Pakistani Punjab. The narrator dives in the depths of his subconscious, shifting between past and present, recalling the different eras of Lahore, its neighbourhoods and the communities that defined them.

Dr Murphy’s research focusing on the vernacular literary and religious traditions of Punjab proved her devotion. The book Grieving for the Pigeons invites us into a world of remembrance. It is a difficult task for the translator to convert creative expressions into a different language that relates to the entire world.

Ahmad says, “I have no hesitation in saying that my stories are based on reality and lifelong experiences while keeping the fiction intact expressing the bitter truths of society in remarkable tone and influential words.”

Lahore has a perceptible presence in the short stories. Its roads, cafes, landmarks and history spellbind the readers. The book is a tornado of thoughts. Walking through the narrow lanes of the old Anarkali in front of the masses, around Mall Road, along with the rallies and protests. We are introduced to Gol Baagh and Laat Sahab, and all of a sudden we wander in the streets of Rome and again return back to the muddy streets of Krishan Nagar where the author spent his childhood to youth.

The narrative revolves around the framework of past, present and future. We see many layers under the complex circumstances. For example, we find the same situation in T. S. Elliot’s poem,

“Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past

If all time is eternally present”

A man sitting in his Krishan Nagar home and seeing at once Lahore, Rome and Batala, he flies in 1947 with the trauma of Partition that shattered the Punjab region and slips down to the 1970s. The slippage between past and present reminds us that time knows no boundaries and no lanes in the mind of a creative writer.

For Dr Anne Murphy, this is her first book-length translation. It is her keen observation and love for history and culture that produced such a masterpiece. She has helped people to understand the obligations of reciprocation and its consequences.

“Pigeons, Ledges and Streets” is narrated in an artistic, cultural and historical way. Dr Murphy tends to depict the characters the same as in the actual story. In “Walli Ullah is lost,” the character of Altaf is portrayed sarcastically.

“Mr. Altaf would not move a muscle, nor would he allow the boys to move away.”

Gamay of “Pigeons, Ledges and Streets,” Naseem of “Rain,” Bajwa, Walliullah and Bali have a realistic flow within the content of the story. Reading them shows us that they are painted with the same creative brush but in different domains.

Dr Murphy has made a successful effort to recognise the culture and heritage of a dynamic city like Lahore in “The Estranged City.”

The last story “Paani di Kandh” is translated by Dr Murphy as “Wall of Water.” It relates the visit of the author to Batala in 2005 in search of his parents’ home. It is a complex story to reach what his parents left in the wake of a bloody partition, and a reunion with his past. The remains of his uncle whispered to him “You have come after sixty years to give me a shroud.”

Dr Murphy uses his own words to profoundly enhance the psychological feelings of the author. A truly appreciable effort that will definitely attract a lot of readers.