Many gifted writers such as Rajinder Singh Bedi, Balwant Singh, Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi, Shaukat Siddiqui, Jamila Hashmi, Mansha Yaad, Khalid Toor, and more recently Ali Akbar Natiq and others have showcased rural Punjab in their major works. Nevertheless, I find Tahira Iqbal to be distinctive due to the unique prose that only she writes and a particular Punjab that only she captures. A prose that is rooted, earthy and punctuated with evocative expressions, terms, phrases and adages from Punjabi as well as the Jaangli dialect. A Punjab that is seen from the eyes of historically persecuted and marginalised women striving against debilitating oppression of class, caste, gender and culture. Her meticulous observation of the rural Punjabi cultural milieu, her empathy for the obscure lives led far below the privileged gaze, and her mastery over local idiom, dialect and manners of speech, helps her create something superb and deeply moving. Add to that her insights into rural economy and feudal sociology, her celebration of the landscape and seasons, and her incorporation of local songs and lore, and one gets a strong and varied flavour of Punjab; especially the stretches between the great rivers or the bars, and in particular the area around Sahiwal. While some have been critical of her mingling of Punjabi and Jaangli with Urdu, I find that to be her strength as it makes her prose so natural and expressive. The great Rajinder Singh Bedi says unabashedly in the preface of one of his collections of short stories that he is a Punjabi and hence writes Punjabi Urdu. Tahira Iqbal continues that valuable tradition which not only furnishes us a prose with a rich local flavour but also makes Urdu literature richer with all its beautiful dialects and regional variations.

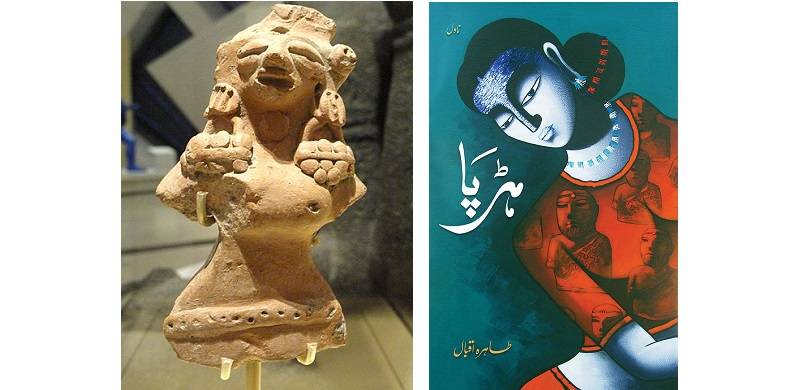

My first experience of her luminous prose was when I read the first section of her famous earlier novel Neeli Bar, called “Bar kai rang, mausam aur log.” It left me enthralled. Her latest, the novel Harappa too has the same prose delights to offer. Harappa the city of course fascinates me beyond measure, deeply interested as I am in our ancient history and present as it is also in my own fiction. The more usual approach to writing about an ancient city is to reimagine it as it were and try and transport the reader to those times. In case of the Indus Valley Civilisation, this has been done very recently in Hina Jamshed’s vibrantly imagined novel Hariyupia that I have also reviewed for this paper, and in my own Chand Ko Gul Karen to Hum Janen. Tahira Iqbal’s modus operandi however steers well clear of the norm. Her Harappa doesn’t exist in an imagined vision. It appears in the facial and physical features of contemporary people, in the twenty first century existence of various disadvantaged communities who inhabit the area surrounding its grand ruins, and in the perpetuation of certain cultural constructs, gender roles, and assorted hegemonies that date back many millennia. Written with depth of feeling, acute sensitivity to the plight of women at the very bottom of the social ladder, and great craft and dexterity, Harappa is therefore unique in its approach. In the grand tradition of wonderful female Urdu novelists - and I believe that they in many ways dominate the genre - she is another highly accomplished practitioner of the art.

My first experience of her luminous prose was when I read the first section of her famous earlier novel Neeli Bar, called “Bar kai rang, mausam aur log.” It left me enthralled. Her latest, the novel Harappa too has the same prose delights to offer. Harappa the city of course fascinates me beyond measure, deeply interested as I am in our ancient history and present as it is also in my own fiction. The more usual approach to writing about an ancient city is to reimagine it as it were and try and transport the reader to those times. In case of the Indus Valley Civilisation, this has been done very recently in Hina Jamshed’s vibrantly imagined novel Hariyupia that I have also reviewed for this paper, and in my own Chand Ko Gul Karen to Hum Janen. Tahira Iqbal’s modus operandi however steers well clear of the norm. Her Harappa doesn’t exist in an imagined vision. It appears in the facial and physical features of contemporary people, in the twenty first century existence of various disadvantaged communities who inhabit the area surrounding its grand ruins, and in the perpetuation of certain cultural constructs, gender roles, and assorted hegemonies that date back many millennia. Written with depth of feeling, acute sensitivity to the plight of women at the very bottom of the social ladder, and great craft and dexterity, Harappa is therefore unique in its approach. In the grand tradition of wonderful female Urdu novelists - and I believe that they in many ways dominate the genre - she is another highly accomplished practitioner of the art.

In Channan and Bali we are presented with two outstanding characters of women striving against poverty and patriarchy, who are inhabitants of modern Harappa. Diminutive, dark and flat featured, Channan appears to be a reincarnation of the ancient people who once lived here. Not unlike the statues in the local museum. The darker Dravidians whose progeny are underlings now. At the bottom of the caste pyramid and dirt poor she may be, her spirit is irrepressible. Bali on the other hand is comely and equally determined. Quite stoically she manages to somehow assert herself and stay afloat in a milieu that reduces her daily to a provider of physical favours and calls her Kanjri. These two and other strong and memorable female characters dominate the first part of the book - “Abad Harappa” - which is my favourite due to brilliant character development, vivid descriptions and rich dialogues. Their experiences typify in many ways what women have faced across the millennia, as civilisations have emerged, clashed and floundered. We also have the indomitable Suniari of the gypsy clan who is the dignified breadwinner of her clan and a woman of aplomb and dignity. Through these characters the author provides great sociological and cultural insights into the lives of different suppressed classes and communities - the Musalli, the Mirasi, the Kammi Kameen, the Khana Badosh and the Pakhiwas. Are they then the true children of ancient Harappa – a race that has been reduced and demeaned over the centuries, is a question that recurs in the novel.

Tahira Iqbal’s other significant preoccupation in her works that I have read is the strangulating repression and misogyny of traditional feudal culture. It was very prominent in Neeli Bar where she also provides a fascinating comparative assessment of the cultural divergences between the indigenous Jangli people of the area, older settlers and landowners, and later settlers who came through British social engineering when they built the canals. Her dismantling and deconstruction of feudalism figures prominently in Harappa as well. A deep anguish permeates her depiction of the adolescent Sanobar who belongs to a rich and highly orthodox and misogynistic feudal family. Her tale is primarily told in the second part of the novel called “Khandar Harappa.” Sanobar’s domineering and heartless mother may at times appear diabolical, but I have long learnt that life often throws up people far more outrageous than our imaginings. Though connected with the first part, this part has a different flavour and essentially captures the horrendous existence of a young woman stuck in a suffocating household. Interestingly, the Harappa of “Abad Harappa” for all its inequities, discriminations and prejudices appears lively and uninhibited due to the freedom of movement of its lower caste women; whilst “Khandar Harappa” is no different from a stagnated, lifeless ruin as patriarchy and misogyny suck out all that is vital and life-enforcing from its captives such as Sanobar.

Tahira Iqbal’s other significant preoccupation in her works that I have read is the strangulating repression and misogyny of traditional feudal culture. It was very prominent in Neeli Bar where she also provides a fascinating comparative assessment of the cultural divergences between the indigenous Jangli people of the area, older settlers and landowners, and later settlers who came through British social engineering when they built the canals. Her dismantling and deconstruction of feudalism figures prominently in Harappa as well. A deep anguish permeates her depiction of the adolescent Sanobar who belongs to a rich and highly orthodox and misogynistic feudal family. Her tale is primarily told in the second part of the novel called “Khandar Harappa.” Sanobar’s domineering and heartless mother may at times appear diabolical, but I have long learnt that life often throws up people far more outrageous than our imaginings. Though connected with the first part, this part has a different flavour and essentially captures the horrendous existence of a young woman stuck in a suffocating household. Interestingly, the Harappa of “Abad Harappa” for all its inequities, discriminations and prejudices appears lively and uninhibited due to the freedom of movement of its lower caste women; whilst “Khandar Harappa” is no different from a stagnated, lifeless ruin as patriarchy and misogyny suck out all that is vital and life-enforcing from its captives such as Sanobar.

Finally, we have the third part called “Harappa Fitrat” which progresses the stories of Channan, Bali and Sanobar as their lives undergo major events and they grapple with the various opportunities and challenges that emerge as a result. This is the most polemical of the three parts, as it takes on the very ‘fitrat’ or nature of the beast. As in the latter half of Neeli Bar there is an endeavour to connect the traditional and the localised with the contemporary and the universal. Unsurprisingly, in the larger world as well hegemony, control and domination persist and manifest themselves in multiple ways. At the same time, the will and spirit of these strong women helps them explore different pathways to potential emancipation.

Though I, too, subscribe to the view that the authorial voice ought not to dominate a narrative. That it is through character development, dialogue and the ‘showing’ of places and events that a book’s underlying politics and ideology should be disseminated. However, overcautiousness on this score can also make literature excessively implicit, suggestive, inferential, bound to conventions of artistic style and hence feeble and obscure. I look upon Tahira Iqbal’s Harappa not just as a piece of inspired storytelling. But also, as an unabashed outburst, a deep lament, a cry of anguish, a stance of defiance, and an act of resistance in a milieu that is largely inured to systemic exploitation of the weak and the repression of women. In such a context, one doesn’t whisper. One screams. This novel is a scream. While at the same time it is also a significant and wonderfully executed piece of literature. For a very original interpretation of the idea of Harappa, its use as a complex metaphor for many ideas and processes, memorable characters, and the hope that it keeps aflicker despite all the surrounding gloom, this is a novel that deserves close attention and wide engagement.

Once more a very well designed and printed book by Jhelum Book Corner.

My first experience of her luminous prose was when I read the first section of her famous earlier novel Neeli Bar, called “Bar kai rang, mausam aur log.” It left me enthralled. Her latest, the novel Harappa too has the same prose delights to offer. Harappa the city of course fascinates me beyond measure, deeply interested as I am in our ancient history and present as it is also in my own fiction. The more usual approach to writing about an ancient city is to reimagine it as it were and try and transport the reader to those times. In case of the Indus Valley Civilisation, this has been done very recently in Hina Jamshed’s vibrantly imagined novel Hariyupia that I have also reviewed for this paper, and in my own Chand Ko Gul Karen to Hum Janen. Tahira Iqbal’s modus operandi however steers well clear of the norm. Her Harappa doesn’t exist in an imagined vision. It appears in the facial and physical features of contemporary people, in the twenty first century existence of various disadvantaged communities who inhabit the area surrounding its grand ruins, and in the perpetuation of certain cultural constructs, gender roles, and assorted hegemonies that date back many millennia. Written with depth of feeling, acute sensitivity to the plight of women at the very bottom of the social ladder, and great craft and dexterity, Harappa is therefore unique in its approach. In the grand tradition of wonderful female Urdu novelists - and I believe that they in many ways dominate the genre - she is another highly accomplished practitioner of the art.

My first experience of her luminous prose was when I read the first section of her famous earlier novel Neeli Bar, called “Bar kai rang, mausam aur log.” It left me enthralled. Her latest, the novel Harappa too has the same prose delights to offer. Harappa the city of course fascinates me beyond measure, deeply interested as I am in our ancient history and present as it is also in my own fiction. The more usual approach to writing about an ancient city is to reimagine it as it were and try and transport the reader to those times. In case of the Indus Valley Civilisation, this has been done very recently in Hina Jamshed’s vibrantly imagined novel Hariyupia that I have also reviewed for this paper, and in my own Chand Ko Gul Karen to Hum Janen. Tahira Iqbal’s modus operandi however steers well clear of the norm. Her Harappa doesn’t exist in an imagined vision. It appears in the facial and physical features of contemporary people, in the twenty first century existence of various disadvantaged communities who inhabit the area surrounding its grand ruins, and in the perpetuation of certain cultural constructs, gender roles, and assorted hegemonies that date back many millennia. Written with depth of feeling, acute sensitivity to the plight of women at the very bottom of the social ladder, and great craft and dexterity, Harappa is therefore unique in its approach. In the grand tradition of wonderful female Urdu novelists - and I believe that they in many ways dominate the genre - she is another highly accomplished practitioner of the art.From Tahira Iqbal's insights into rural economy and feudal sociology, her celebration of the landscape and seasons and her incorporation of local songs and lore, one gets a strong and varied flavour of Punjab; especially the stretches between the great rivers or the bars

In Channan and Bali we are presented with two outstanding characters of women striving against poverty and patriarchy, who are inhabitants of modern Harappa. Diminutive, dark and flat featured, Channan appears to be a reincarnation of the ancient people who once lived here. Not unlike the statues in the local museum. The darker Dravidians whose progeny are underlings now. At the bottom of the caste pyramid and dirt poor she may be, her spirit is irrepressible. Bali on the other hand is comely and equally determined. Quite stoically she manages to somehow assert herself and stay afloat in a milieu that reduces her daily to a provider of physical favours and calls her Kanjri. These two and other strong and memorable female characters dominate the first part of the book - “Abad Harappa” - which is my favourite due to brilliant character development, vivid descriptions and rich dialogues. Their experiences typify in many ways what women have faced across the millennia, as civilisations have emerged, clashed and floundered. We also have the indomitable Suniari of the gypsy clan who is the dignified breadwinner of her clan and a woman of aplomb and dignity. Through these characters the author provides great sociological and cultural insights into the lives of different suppressed classes and communities - the Musalli, the Mirasi, the Kammi Kameen, the Khana Badosh and the Pakhiwas. Are they then the true children of ancient Harappa – a race that has been reduced and demeaned over the centuries, is a question that recurs in the novel.

Tahira Iqbal’s other significant preoccupation in her works that I have read is the strangulating repression and misogyny of traditional feudal culture. It was very prominent in Neeli Bar where she also provides a fascinating comparative assessment of the cultural divergences between the indigenous Jangli people of the area, older settlers and landowners, and later settlers who came through British social engineering when they built the canals. Her dismantling and deconstruction of feudalism figures prominently in Harappa as well. A deep anguish permeates her depiction of the adolescent Sanobar who belongs to a rich and highly orthodox and misogynistic feudal family. Her tale is primarily told in the second part of the novel called “Khandar Harappa.” Sanobar’s domineering and heartless mother may at times appear diabolical, but I have long learnt that life often throws up people far more outrageous than our imaginings. Though connected with the first part, this part has a different flavour and essentially captures the horrendous existence of a young woman stuck in a suffocating household. Interestingly, the Harappa of “Abad Harappa” for all its inequities, discriminations and prejudices appears lively and uninhibited due to the freedom of movement of its lower caste women; whilst “Khandar Harappa” is no different from a stagnated, lifeless ruin as patriarchy and misogyny suck out all that is vital and life-enforcing from its captives such as Sanobar.

Tahira Iqbal’s other significant preoccupation in her works that I have read is the strangulating repression and misogyny of traditional feudal culture. It was very prominent in Neeli Bar where she also provides a fascinating comparative assessment of the cultural divergences between the indigenous Jangli people of the area, older settlers and landowners, and later settlers who came through British social engineering when they built the canals. Her dismantling and deconstruction of feudalism figures prominently in Harappa as well. A deep anguish permeates her depiction of the adolescent Sanobar who belongs to a rich and highly orthodox and misogynistic feudal family. Her tale is primarily told in the second part of the novel called “Khandar Harappa.” Sanobar’s domineering and heartless mother may at times appear diabolical, but I have long learnt that life often throws up people far more outrageous than our imaginings. Though connected with the first part, this part has a different flavour and essentially captures the horrendous existence of a young woman stuck in a suffocating household. Interestingly, the Harappa of “Abad Harappa” for all its inequities, discriminations and prejudices appears lively and uninhibited due to the freedom of movement of its lower caste women; whilst “Khandar Harappa” is no different from a stagnated, lifeless ruin as patriarchy and misogyny suck out all that is vital and life-enforcing from its captives such as Sanobar.Finally, we have the third part called “Harappa Fitrat” which progresses the stories of Channan, Bali and Sanobar as their lives undergo major events and they grapple with the various opportunities and challenges that emerge as a result. This is the most polemical of the three parts, as it takes on the very ‘fitrat’ or nature of the beast. As in the latter half of Neeli Bar there is an endeavour to connect the traditional and the localised with the contemporary and the universal. Unsurprisingly, in the larger world as well hegemony, control and domination persist and manifest themselves in multiple ways. At the same time, the will and spirit of these strong women helps them explore different pathways to potential emancipation.

Though I, too, subscribe to the view that the authorial voice ought not to dominate a narrative. That it is through character development, dialogue and the ‘showing’ of places and events that a book’s underlying politics and ideology should be disseminated. However, overcautiousness on this score can also make literature excessively implicit, suggestive, inferential, bound to conventions of artistic style and hence feeble and obscure. I look upon Tahira Iqbal’s Harappa not just as a piece of inspired storytelling. But also, as an unabashed outburst, a deep lament, a cry of anguish, a stance of defiance, and an act of resistance in a milieu that is largely inured to systemic exploitation of the weak and the repression of women. In such a context, one doesn’t whisper. One screams. This novel is a scream. While at the same time it is also a significant and wonderfully executed piece of literature. For a very original interpretation of the idea of Harappa, its use as a complex metaphor for many ideas and processes, memorable characters, and the hope that it keeps aflicker despite all the surrounding gloom, this is a novel that deserves close attention and wide engagement.

Once more a very well designed and printed book by Jhelum Book Corner.