The newly sworn-in Chief Minister in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Ali Amin Khan Gandapur, while addressing a meeting of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) leaders at the Chief Minister’s House, insinuated initiating a local train service on a build, operate and transfer (BOT) model in Peshawar to address the growing traffic congestion problem in the city. Given the backdrop of the budgetary deficit and the state teetering on the verge of bankruptcy just a few errands ago, there is a pressing need to critically canvass the ontology of undertaking such a massive project. By letting the past usher the future, a full-fledged varied interrogation that seeks to ask what has been done, what the shortcomings were and what impedes the bridging process, we can understand how to address growing needs.

The state of affairs

Interestingly, Pakistan has earned the moniker 'graveyard of development projects' from economists, owing to the fervent pursuit of optics by our leaders. These promises, often centered around embarking on a myriad of mega-project, initially positioned them as the most 'electable.' However, it was revealed by an IMF report that at the federation, 244 new projects, costing Rs 2.26 trillion in FY 2023 were added to the long list of 909 unfinished projects, costing a total of Rs 10.32 trillion — an outright aberrance from the budgeted Rs. 727.5 billion for all the aforementioned schemes. Moreover, it is estimated that the provincial bucket list even transcends the overwhelming federal one.

Peshawar, the capital of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Northwest Pakistan, covers an area of 1,257 km2. The city has witnessed rapid population growth, nearly doubling from 2.027 million for the district to 4.267 million by 2017, and is projected to reach over 7.0 million by 2030 based on current growth rates. Despite being the sixth-largest city in the nation and the most significant contributor (19%) to the GDP of the province, it has remained an unchartered area as far as the earnest attention of political leadership is concerned vis-à-vis their constituencies. With an estimated 40% of the population living below the poverty line, Peshawar has also been a generous host to over 400,000 Afghan refugees.

What truly needs to be instilled is an understanding that an urban system is a holistic continuum—not a collection of isolated projects—and should always be envisioned on a broader canvas. Rather than treating cities as mere spaces for development, they should be viewed as shared spaces with collective ownership, transcending into an entity that fosters innovation and growth.

According to research conducted by the Sustainable Energy and Economic Development (SEED), KPK has been subject to a stupefying 18.8% urbanization rate, with its capital city, flaunting an urbanization rate exceeding 45%. Peshawar alone caters to nearly one-third (approximately 2 million) of the province's total urban population, if nearby cities are excluded. When neighboring cities are included, Peshawar represents half of the urban population of the entire province. This rapid urbanization has come at the expense of non-motorized and public transportation options, exacerbating inequalities and fueling the demand for cars. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Peshawar has emerged as a hub for motorized vehicles. By the end of 2020, in totality 850,000 motor vehicles (MV) were registered, with Peshawar accounting for the highest number of registrations at 42.7% among all districts in KPK.

Peshawar Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Corridor Project

In response to these challenges, the Peshawar Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Corridor Project was initiated in 2013 and became operational by 2020, despite challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since its implementation, the BRT system has achieved remarkable accolades, inter-alia, a record ridership of 280,000 passengers per day, with over 30% female ridership juxtaposed to the pre-BRT meagre ridership of 2%. Moreover, it has led to a reduction in travel time along the city’s east-west corridor by over 60%, an increase in cycling trips, promotion of sustainable transportation modes, and a reduction of 31,000 tons of CO2 emissions in a single year.

While successes deserve acknowledgement, it's equally important to highlight slip ups with the same vigor.

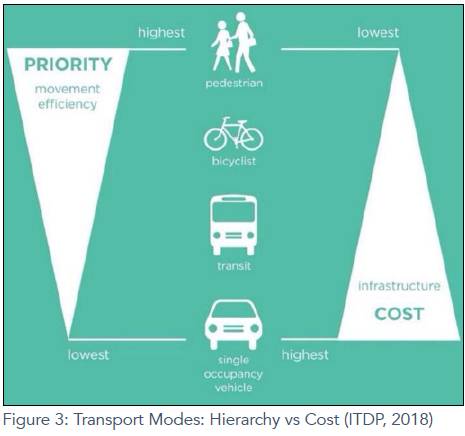

The outlandish cost of construction is estimated to be around Rs. 160 billion, or $593 million. To fully comprehend the magnitude of this expenditure, as per a policy note published by Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), spending Rs. 30 billion on a locally-funded BRT could instead support the operation of 2,000 normal (non-dedicated-route) buses. Following this rationale, the investment of such a substantial amount in a non-dedicated route bus system could have facilitated the operation of approximately more than ten thousand buses. A clearer understanding of the efficiency versus cost of public transport reveals that the government invests in the highest cost infrastructure, which clearly indicates the government's priorities when allocating public funds.

In order to safeguard the livelihoods of the existing public transport operators and maximize the utility of the transport system, an initiative viz. The Bus Industry Restructuring Program was launched. This program aimed at urban mobility within the ambit of the BRT system with the ultimate goal of eliminating informal mobility altogether. However, this initiative has not yet achieved its intended success, as archaic informal mobility programs, including old buses and wagons are still lingering in the city and hence contributing a lion's share to the overwhelming congestion alongside the BRT corridor.

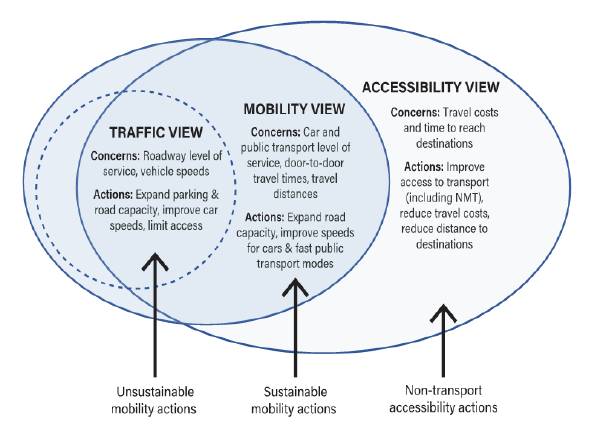

The neglected accessibility lens of the transport system hinders access to people seeking transportation services. A paradigm shift is being experienced in urban transport planning: the realm of change encompasses problem identification, solution generation, and evaluation of previously identified issues.

Another eerie construction which needs to be ameliorated is the failure to acknowledge the precedence of pedestrians over vehicle owners. Cities are meant for people on foot, not for roads and heavy machineries, with all the nuisance strangulating accessibility to the open spaces.

Essentially, the once narrow focus on traffic, which evaluates transportation based solely on motor vehicle speed and operating costs, is being replaced by a broader lens of accessibility. This lens evaluates the transportation system based on its ability to facilitate access to desired services and activities for both people and businesses.

Against the backdrop of the parochial mindset, the issue many face is the lack of secondary infrastructure — while there is a demand and a fitting supply, the intermediary bridging the two is absent. Despite living close to a BRT station, I still have to walk 3-4 km daily. Many people, due to their less-than-ideal first and last mile experiences, opt out of using public transport altogether, thus diminishing its utility.

The need for recalibration

In essence, what truly needs to be instilled is an understanding that an urban system is a holistic continuum—not a collection of isolated projects—and should always be envisioned on a broader canvas. Rather than treating cities as mere spaces for development, they should be viewed as shared spaces with collective ownership, transcending into an entity that fosters innovation and growth.

Another eerie construction which needs to be ameliorated is the failure to acknowledge the precedence of pedestrians over vehicle owners. Cities are meant for people on foot, not for roads and heavy machineries, with all the nuisance strangulating accessibility to the open spaces.

These spaces should serve as catalysts for idea generation and provide opportunities for all to thrive. As Dr. Nadeem Ul Haque aptly stated: “creative cities enhance individual productivity. In the post-industrial information age, creativity creates value. Creative cities are multiethnic, open to immigration, culturally rich, dense, and full of learning and innovation. They also allow for eccentricity, and offer many diverse learning experiences. In well-organized societies, productivity increases and energies converge to produce innovation and fresh ideas.”

In light of these concerns, as a resident of Peshawar, I am not very enthused about the idea of a local train service given the lacunae which can be filled in the current status quo, which includes the BRT system we already have. Let's hope decision-makers prioritize rationalizing what has already been done instead of embarking on another haphazard venture.