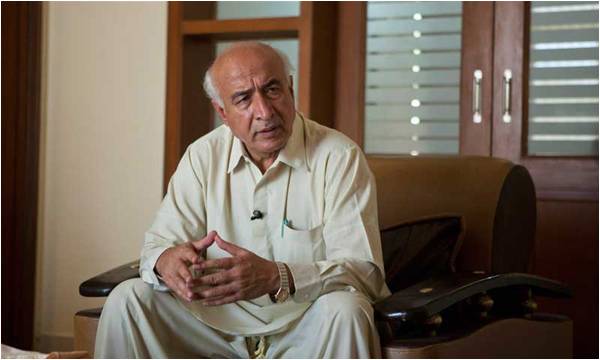

Dr Abdul Malik Baloch became the first chief minister of Balochistan after the May 2013 elections, some say “due to the political wisdom of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif”. He is the first chief executive of the province to come from a middle-class background, and he is not a tribal elder. His party did not win a majority in the province, but he was nominated for his nationalist credentials.

“He has made the dysfunctional Balochistan government functional,” says Behram Baloch, who edits a bilingual magazine in Quetta. He has controlled law and order across the restive province to a great extent – especially in Makran and Khuzdar, where abduction for ransom and assassinations have waned, he said.

“He wants to carry out revolutionary governance reforms, but the system does not allow him to do that,” said Naqeeb Zaib Kakar, a teacher based in Quetta.

Qayyum Gichki, a resident of Balochistan’s Panjgur district, does not agree. “On the whole, his performance is not satisfactory,” he said. Qayyum said the chief minister had made “tall claims”, and people had expectations from him because he belonged to the middle class, but he did not fulfill his promises. “He said in a speech in Balochistan Assembly that he would resign if he failed to serve the people of the province.”

Noor Ahmed, who is a writer, says a new policy to recruit teachers on merit, and the establishment of new educational institutions in Balochistan are important moves. “Despite these,” he says, “Balochistan’s key issues remain unresolved.” Noor believes the province is “politically and naturally a tough region”.

Ali Raza Rind, an Urdu columnist, believes Dr Baloch “tried a lot to do what he had promised”, but he could not. “For example, his first step – an ‘educational emergency’ in Balochistan – failed to meet its goals.” Reforms in the health sector and a job creation plan were cancelled because they did not work, he added. He acknowledged that law and order had improved, and the government deserved credit for that.

“There is an acute leadership crisis in the parliamentary politics of Pakistan,” according to Shahjahan Zehir, a social worker. “When Dr Abdul Malik Baloch became the chief minister, a group of optimists had great hopes from him. People were full of nationalistic enthusiasm.” But the chief minister was “good but not excellent”, he said. “He still talks about education, health and development, but he has turned a blind eye towards Balochistan’s core issues.”

Asghar Kakar, a resident of the Quetta city, believes Dr Abdul Malik Baloch did well, because “he put a tight check on corruption and other evils that plague the whole nation.”

Anwar Sajidi, the editor of the Urdu daily Intekhab, believes corruption has increased. He cited media reports of graft allegations against ministers belonging to Dr Abdul Malik Baloch’s National Party.

In 2014, Dr Abdul Baloch appointed Arsalan Iftikhar, the son of former chief justice Iftikhar Chaudhry, as the vice chairman of the Board of Investment in Balochistan. He too had been accused of deception and corruption in the past. In the beginning, the chief minister stood by him. But after an uproar in the media, he was compelled to ask for Arsalan’s resignation.

Jaffer Baloch, who is a worker of the National Party, claims that the political and economic situation in Balochistan has improved, and law and order problems in Quetta have also decreased. “The chief minister is working on setting up new universities in the province, upgrading schools, improving the procedure for the appointment of teachers, and cracking down on ghost schools, teachers and students,” he said. “Importantly, it is due to his tireless efforts that the dissident Baloch leaders are showing interest in negotiations.” Balochistan was the first province to conduct local council elections, and that is evidence of strong governance, he added.

But Dr Ababagar Baloch, a young educationist in Islamabad, believes these measures are “limited to newspaper statements”. He especially complained about a lack of provincial government scholarships for students from Balochistan studying in other provinces.

“When Dr Abdul Malik Baloch was nominated as chief executive, he did not have a policy,” said Shabbir Rakhshani, a freelance columnist. “The focus of his government was on security issues. With the help of security forces, he has managed to normalize the situation to some extent, but when it comes to social and political issues, the government has not been able to do much.”

While his critics cite acid attacks on women and the closing down of schools in Panjgur district because of threats and intimidation to argue that law and order are still a major concern, jury is still out on how Dr Abdul Malik Baloch has performed so far.

“He has made the dysfunctional Balochistan government functional,” says Behram Baloch, who edits a bilingual magazine in Quetta. He has controlled law and order across the restive province to a great extent – especially in Makran and Khuzdar, where abduction for ransom and assassinations have waned, he said.

“He wants to carry out revolutionary governance reforms, but the system does not allow him to do that,” said Naqeeb Zaib Kakar, a teacher based in Quetta.

Qayyum Gichki, a resident of Balochistan’s Panjgur district, does not agree. “On the whole, his performance is not satisfactory,” he said. Qayyum said the chief minister had made “tall claims”, and people had expectations from him because he belonged to the middle class, but he did not fulfill his promises. “He said in a speech in Balochistan Assembly that he would resign if he failed to serve the people of the province.”

Noor Ahmed, who is a writer, says a new policy to recruit teachers on merit, and the establishment of new educational institutions in Balochistan are important moves. “Despite these,” he says, “Balochistan’s key issues remain unresolved.” Noor believes the province is “politically and naturally a tough region”.

Ali Raza Rind, an Urdu columnist, believes Dr Baloch “tried a lot to do what he had promised”, but he could not. “For example, his first step – an ‘educational emergency’ in Balochistan – failed to meet its goals.” Reforms in the health sector and a job creation plan were cancelled because they did not work, he added. He acknowledged that law and order had improved, and the government deserved credit for that.

“There is an acute leadership crisis in the parliamentary politics of Pakistan,” according to Shahjahan Zehir, a social worker. “When Dr Abdul Malik Baloch became the chief minister, a group of optimists had great hopes from him. People were full of nationalistic enthusiasm.” But the chief minister was “good but not excellent”, he said. “He still talks about education, health and development, but he has turned a blind eye towards Balochistan’s core issues.”

Asghar Kakar, a resident of the Quetta city, believes Dr Abdul Malik Baloch did well, because “he put a tight check on corruption and other evils that plague the whole nation.”

"There is an acute leadership crisis in the parliamentary politics of Pakistan"

Anwar Sajidi, the editor of the Urdu daily Intekhab, believes corruption has increased. He cited media reports of graft allegations against ministers belonging to Dr Abdul Malik Baloch’s National Party.

In 2014, Dr Abdul Baloch appointed Arsalan Iftikhar, the son of former chief justice Iftikhar Chaudhry, as the vice chairman of the Board of Investment in Balochistan. He too had been accused of deception and corruption in the past. In the beginning, the chief minister stood by him. But after an uproar in the media, he was compelled to ask for Arsalan’s resignation.

Jaffer Baloch, who is a worker of the National Party, claims that the political and economic situation in Balochistan has improved, and law and order problems in Quetta have also decreased. “The chief minister is working on setting up new universities in the province, upgrading schools, improving the procedure for the appointment of teachers, and cracking down on ghost schools, teachers and students,” he said. “Importantly, it is due to his tireless efforts that the dissident Baloch leaders are showing interest in negotiations.” Balochistan was the first province to conduct local council elections, and that is evidence of strong governance, he added.

But Dr Ababagar Baloch, a young educationist in Islamabad, believes these measures are “limited to newspaper statements”. He especially complained about a lack of provincial government scholarships for students from Balochistan studying in other provinces.

“When Dr Abdul Malik Baloch was nominated as chief executive, he did not have a policy,” said Shabbir Rakhshani, a freelance columnist. “The focus of his government was on security issues. With the help of security forces, he has managed to normalize the situation to some extent, but when it comes to social and political issues, the government has not been able to do much.”

While his critics cite acid attacks on women and the closing down of schools in Panjgur district because of threats and intimidation to argue that law and order are still a major concern, jury is still out on how Dr Abdul Malik Baloch has performed so far.