It was early in the morning and the chief security officer of the then President Farooq Ahmad Khan Leghari had decided to make a courtesy call on the just ‘relieved’ Chief Justice of Pakistan Sajjad Ali Shah who was staying at the Punjab House in Islamabad. Having hurtled through a roller coaster of developments which had, unprecedentedly, involved a bench of the same Supreme Court ousting him as the Chief Justice while mainly relying on the landmark Al-Jehad case, ironically authored by Justice Shah himself.

In a high voltage drama which saw the Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif summoned in person to Shah’s court for contempt of court, the bench headed by Chief Justice Shah suspending the 12th Amendment to the Constitution proved the proverbial last straw that broke the camel’s back.

Just a brief tour de force of our political/judicial history first. Anxious to undo the disfigurement done to the constitution during Zia years, the prime minister Nawaz Sharif had especially telephoned President Leghari informing him of his decision to repeal Article 58(2)(b) -- the perennial bane in the political power struggle leading to frequent palace intrigues and the resultant civil-military skirmishes often leading to the overthrowing of elected governments -- later rubber stamped by the Supreme Court which conveniently served as the final icing on the cake.

As could be reasonably discerned, the president spending the weekend at his village in the far flung Dera Ghazi Khan had felt denuded of his powers which he had exercised to cut short the tenure of his own party’s government headed by Benazir Bhutto barely a year ago. The capital was once again possessed by waves of negative energy with opposing powers jostling and furiously wrestling for ascendency, the elected government spearheaded by the PML-N versus the military establishment fronted by president Leghari. A mouth watering and yet a troubling prospect.

Almost a decade of democracy post Zia’s martial law had pushed overt military figures in the background generating a faux self belief in the political elites to be the frontline protagonists only for the roles to be reversed a year later by General Musharraf and his small coterie of power hungry generals.

In a country where both military and civilian leaders begin to harbor dreams of grandeur and destiny in terms of Providence choosing them for performing a history making task immediately after assuming the role of a ruler, Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah, unsurprisingly, had not seemed immune from this delusion albeit to a lesser degree while displaying a slightly different comportment.

General Zia-ul-Haq genuinely believed himself to be the chosen one to enforce ‘Islami Nizam’ to Pakistan till he was blown out of the sky in 1988, whereas Ayub Khan never concealed his personal perception of his special, ‘anointed’ role in reforming the country. The latter’s frequent and risible use of the phrase ‘the hour had struck’ in his rather tedious autobiography Friends not Masters demonstrates the highest sense of entitlement possible, as the anecdote goes.

The well-meaning and conscientious chief justice seemed perfectly happy to throw his own spanner in the works by upping the ante against the Nawaz government by suspending, of all things, a constitutional amendment passed by both houses of the parliament. “Is everything ok?”, he had feebly asked Leghari’s emissary fearing the tables had been turned and the unthinkable had happened. Those present could guess that he apprehended his imminent arrest.

The senior officer heading the police team, detecting fear in the judge’s eyes, who had staggered out of his bedroom barefooted, promptly delivered president Leghari’s message of solidarity and best wishes to assuage his anxieties. And hence the arrest of a chief justice was averted, a spectre that had loomed ominously ever since the days of justice MR Kayani when Ayub Khan and his cronies had almost decided to arrest the unmanageable and flippant judge.

The unenviable feather of arresting not only the Chief Justice of Pakistan but also ‘laying off’ almost the entire superior judiciary finally adorned the cap of General Musharraf in the twilight of his rule, as we all know to our detriment.

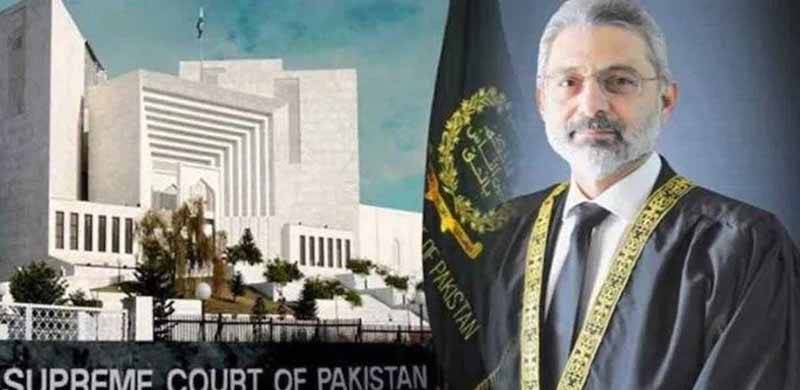

The current saga of a five member bench of the Supreme Court in a dramatic turn of events ‘transferring’ and fixing a suo motu matter before itself involving the right of freedom of expression guaranteed under Article 19, which was earlier pending before a two member judge headed by Justice Qazi Faez Isa, has similarities in form with the Justice Shah episode. But the substance may not be identical. Consider:

Although Chief Justice Shah was not known for his fondness for suo motu powers of the Supreme Court, his strong urge to reform the system even if that often meant assuming powers of the executive motivated by the faux sense of destiny had an unmistakable and overpowering flavour of the ‘chosen one’ storyline. If we ignore for a moment the ensuing anomalies and confusion in the wake of suo motu notices taken by erstwhile Chief Justices—in particular Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry and Saqib Nisar JJ—both suo motu notices taken by Qazi Faez J were against the ever increasing role of intelligence agencies and not against governments of the day.

Unlike in the past when majority of suo motu actions were directed against sitting governments sticking to the classic and old-fashioned principle of the Supreme Court stepping in when administrative structure had seemingly collapsed, the judgment rendered on the TLP dharna in 2017 had in essence frowned upon and questioned the role of military officers in brokering a deal in ending the sit-in.

Although the latest suo motu case which involves recent incidents of intimidation and physical attacks on journalists, including an assassination attempt on a senior journalist Absar Alam may be deemed to be within the administrative domain of the PTI government on paper, the culpability in the public perception is placed squarely with the murky web of operatives belonging to intelligence agencies.

The similarities with the Justice Shah episode ended when the five member bench started hearing the matter prompting many of the journalists who were initially party to the proceedings to withdraw their applications and Justice Qazi Faez Isa leaving the country for his wife’s medical treatment.

It is not hard to predict the outcome. Suffice it to say, it will most probably go down as another sordid chapter in our judicial history where the pragmatism of ‘protecting the state’ will upstage all constitutionally guaranteed human rights once again.

To describe a patently depressing state of affairs, Molvi Tamizuddin, the Bhutto trial, Nusrat Bhutto case, Zafar Ali Shah case and the Panama trials are just a few notable examples from a long list of judgments that have served to perpetuate the stagnant status quo at the expense of the elusive rule of law in the country.

Perhaps it’s time for the Supreme Court to let a breath of fresh air by revisiting the aforementioned judgments. It is also time to quote Khalil Gibran’s poem, 'Pity the Nation' in the right context of injustices wrought by dictatorships and not to heap scorn over hapless politicians. I leave you with Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani’s poignant lines in the hope that soon dark pessimism will be replaced by light and good times:

Would you permit me?

In a country where thinkers are assassinated,

and writers are considered infidels

and books are burnt,

in societies that refuse the other,

and force silence on mouths and

thoughts forbidden,

and to question is a sin,

I beg your pardon, would you permit me?

Would you permit me to bring up

my children as I want,

and not to dictate on me your whims and orders?

……………………………………………………

……………………………………………………

would you permit me?

In a high voltage drama which saw the Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif summoned in person to Shah’s court for contempt of court, the bench headed by Chief Justice Shah suspending the 12th Amendment to the Constitution proved the proverbial last straw that broke the camel’s back.

Just a brief tour de force of our political/judicial history first. Anxious to undo the disfigurement done to the constitution during Zia years, the prime minister Nawaz Sharif had especially telephoned President Leghari informing him of his decision to repeal Article 58(2)(b) -- the perennial bane in the political power struggle leading to frequent palace intrigues and the resultant civil-military skirmishes often leading to the overthrowing of elected governments -- later rubber stamped by the Supreme Court which conveniently served as the final icing on the cake.

As could be reasonably discerned, the president spending the weekend at his village in the far flung Dera Ghazi Khan had felt denuded of his powers which he had exercised to cut short the tenure of his own party’s government headed by Benazir Bhutto barely a year ago. The capital was once again possessed by waves of negative energy with opposing powers jostling and furiously wrestling for ascendency, the elected government spearheaded by the PML-N versus the military establishment fronted by president Leghari. A mouth watering and yet a troubling prospect.

Almost a decade of democracy post Zia’s martial law had pushed overt military figures in the background generating a faux self belief in the political elites to be the frontline protagonists only for the roles to be reversed a year later by General Musharraf and his small coterie of power hungry generals.

In a country where both military and civilian leaders begin to harbor dreams of grandeur and destiny in terms of Providence choosing them for performing a history making task immediately after assuming the role of a ruler, Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah, unsurprisingly, had not seemed immune from this delusion albeit to a lesser degree while displaying a slightly different comportment.

General Zia-ul-Haq genuinely believed himself to be the chosen one to enforce ‘Islami Nizam’ to Pakistan till he was blown out of the sky in 1988, whereas Ayub Khan never concealed his personal perception of his special, ‘anointed’ role in reforming the country. The latter’s frequent and risible use of the phrase ‘the hour had struck’ in his rather tedious autobiography Friends not Masters demonstrates the highest sense of entitlement possible, as the anecdote goes.

Almost a decade of democracy post Zia’s martial law had pushed overt military figures in the background generating a faux self belief in the political elites to be the frontline protagonists only for the roles to be reversed a year later by General Musharraf and his small coterie of power hungry generals.

The well-meaning and conscientious chief justice seemed perfectly happy to throw his own spanner in the works by upping the ante against the Nawaz government by suspending, of all things, a constitutional amendment passed by both houses of the parliament. “Is everything ok?”, he had feebly asked Leghari’s emissary fearing the tables had been turned and the unthinkable had happened. Those present could guess that he apprehended his imminent arrest.

The senior officer heading the police team, detecting fear in the judge’s eyes, who had staggered out of his bedroom barefooted, promptly delivered president Leghari’s message of solidarity and best wishes to assuage his anxieties. And hence the arrest of a chief justice was averted, a spectre that had loomed ominously ever since the days of justice MR Kayani when Ayub Khan and his cronies had almost decided to arrest the unmanageable and flippant judge.

The unenviable feather of arresting not only the Chief Justice of Pakistan but also ‘laying off’ almost the entire superior judiciary finally adorned the cap of General Musharraf in the twilight of his rule, as we all know to our detriment.

The current saga of a five member bench of the Supreme Court in a dramatic turn of events ‘transferring’ and fixing a suo motu matter before itself involving the right of freedom of expression guaranteed under Article 19, which was earlier pending before a two member judge headed by Justice Qazi Faez Isa, has similarities in form with the Justice Shah episode. But the substance may not be identical. Consider:

Although Chief Justice Shah was not known for his fondness for suo motu powers of the Supreme Court, his strong urge to reform the system even if that often meant assuming powers of the executive motivated by the faux sense of destiny had an unmistakable and overpowering flavour of the ‘chosen one’ storyline. If we ignore for a moment the ensuing anomalies and confusion in the wake of suo motu notices taken by erstwhile Chief Justices—in particular Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry and Saqib Nisar JJ—both suo motu notices taken by Qazi Faez J were against the ever increasing role of intelligence agencies and not against governments of the day.

Unlike in the past when majority of suo motu actions were directed against sitting governments sticking to the classic and old-fashioned principle of the Supreme Court stepping in when administrative structure had seemingly collapsed, the judgment rendered on the TLP dharna in 2017 had in essence frowned upon and questioned the role of military officers in brokering a deal in ending the sit-in.

Although the latest suo motu case which involves recent incidents of intimidation and physical attacks on journalists, including an assassination attempt on a senior journalist Absar Alam may be deemed to be within the administrative domain of the PTI government on paper, the culpability in the public perception is placed squarely with the murky web of operatives belonging to intelligence agencies.

Although Chief Justice Shah was not known for his fondness for suo motu powers of the Supreme Court, his strong urge to reform the system even if that often meant assuming powers of the executive motivated by the faux sense of destiny had an unmistakable and overpowering flavour of the ‘chosen one’ storyline.

The similarities with the Justice Shah episode ended when the five member bench started hearing the matter prompting many of the journalists who were initially party to the proceedings to withdraw their applications and Justice Qazi Faez Isa leaving the country for his wife’s medical treatment.

It is not hard to predict the outcome. Suffice it to say, it will most probably go down as another sordid chapter in our judicial history where the pragmatism of ‘protecting the state’ will upstage all constitutionally guaranteed human rights once again.

To describe a patently depressing state of affairs, Molvi Tamizuddin, the Bhutto trial, Nusrat Bhutto case, Zafar Ali Shah case and the Panama trials are just a few notable examples from a long list of judgments that have served to perpetuate the stagnant status quo at the expense of the elusive rule of law in the country.

Perhaps it’s time for the Supreme Court to let a breath of fresh air by revisiting the aforementioned judgments. It is also time to quote Khalil Gibran’s poem, 'Pity the Nation' in the right context of injustices wrought by dictatorships and not to heap scorn over hapless politicians. I leave you with Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani’s poignant lines in the hope that soon dark pessimism will be replaced by light and good times:

Would you permit me?

In a country where thinkers are assassinated,

and writers are considered infidels

and books are burnt,

in societies that refuse the other,

and force silence on mouths and

thoughts forbidden,

and to question is a sin,

I beg your pardon, would you permit me?

Would you permit me to bring up

my children as I want,

and not to dictate on me your whims and orders?

……………………………………………………

……………………………………………………

would you permit me?