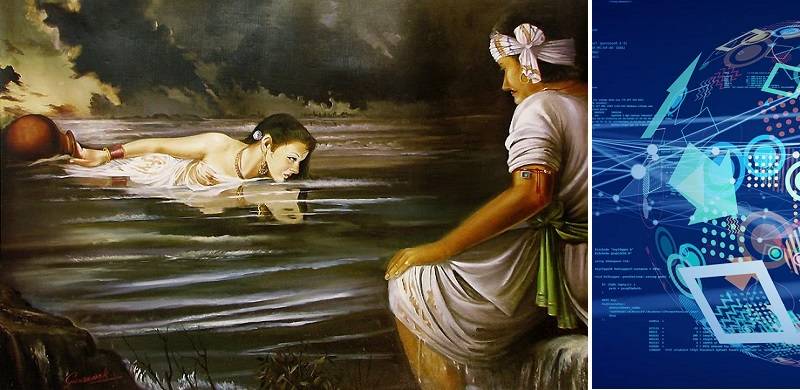

The contemporary world is building a cyber-megalopolis. This Internet super city is going to house goods from various parts of the planet. Its beauty lies in its openness and accessibility to all. Its ugliness in its exclusiveness. The disadvantage of living in a fully globalised and online world can be that most of the omnipresent ‘global’ will have little or no share from our ‘local.’ The online representation of Pakistan’s cultural products has been much lower than even the proverbial salt in dough – at least so far. The greatest mass of our cultural heritage is in our centuries-old tradition of folklore, something we could proudly showcase anywhere on the planet—in cyberworlds or so-called metaverses.

The question of why we must take our folklore into the clouds of the internet can have as many answers as the dreams that bedtime stories sow in our children’s eyes. Digitizing folklore means the safe handing-off of our folk wisdom to the generations to arrive. This would prevent the youth of our part of the world be alienated in the streets and bazaars of the Internet. This would save them from being vulnerable to various kinds of supremacists from around the globe. This could be a remedy for a sense of rootlessness and inferiority in the midst of all the colonising narratives. Sharing 5,000-years-old wisdom with the rest of the world is also a responsibility.

While on one hand the Internet functions as a Qissa Khwani Bazaar to house what Simon Bronner terms as Internet folklore—a range of textual, visual and oral narratives, including memes etc.—, on the other, it is an important tool to not only preserve but also revive folkloric culture. In his book, Forget English! Orientalisms and World Literatures, Aamir Mufti points to the absence of literature from contexts like ours on Western library shelves dedicated to so-called “world literature.” This absence speaks of a colonial mindset and a politics of representation. The question of why Pakistani literature has failed to reach global audiences is also often answered with the excuse that ours is an oral literary tradition and most of our best stories, songs and tales are not scripted.

Yesterday’s helplessness seems to have a remedy in today’s innovative technologies. Digital tools now empower the spoken word. Broadcasting has been democratised to some extent. Audiobooks are already in situ. Digital libraries have brought literature—written and oral—onto our laps. Digital Humanities is growing as a discipline. Corpus and computational linguistics are turning literary critics into positivists. Quantification is being normalized in literary studies. The availability of high-quality recording gadgets, high-speed uploading, dynamic websites, cloud storage, social-media networks etc. leaves us with no excuse. It is time to compute our languages and digitize our folk literature.

Under a Higher Education Commission (HEC) sponsored project “Digitizing Folk Wisdom: A project of collection, translation and study of folk literature in major Pakistani languages,” we are working on identifying and introducing folk literary genres, and collecting, transcribing, translating and digitizing pieces from these genres coming from seven Pakistani languages (Balochi, Brahui, Pashto, Punjabi, Saraiki, Sindhi and Urdu) in the first phase. Alert to the changing needs of the time, we are working, conscious of the fact that staying in contact with our past is significant, as a better sense of our heritage helps us better understand why we are where we are today. We are here—exactly where you are reading this article, reading my lament over our absence from an Internet space which is over-showcasing the global. It is a global that is disproportionate. This new world (dis)order calls for action.

Join hands!

The question of why we must take our folklore into the clouds of the internet can have as many answers as the dreams that bedtime stories sow in our children’s eyes. Digitizing folklore means the safe handing-off of our folk wisdom to the generations to arrive. This would prevent the youth of our part of the world be alienated in the streets and bazaars of the Internet. This would save them from being vulnerable to various kinds of supremacists from around the globe. This could be a remedy for a sense of rootlessness and inferiority in the midst of all the colonising narratives. Sharing 5,000-years-old wisdom with the rest of the world is also a responsibility.

While on one hand the Internet functions as a Qissa Khwani Bazaar to house what Simon Bronner terms as Internet folklore—a range of textual, visual and oral narratives, including memes etc.—, on the other, it is an important tool to not only preserve but also revive folkloric culture. In his book, Forget English! Orientalisms and World Literatures, Aamir Mufti points to the absence of literature from contexts like ours on Western library shelves dedicated to so-called “world literature.” This absence speaks of a colonial mindset and a politics of representation. The question of why Pakistani literature has failed to reach global audiences is also often answered with the excuse that ours is an oral literary tradition and most of our best stories, songs and tales are not scripted.

Yesterday’s helplessness seems to have a remedy in today’s innovative technologies. Digital tools now empower the spoken word. Broadcasting has been democratised to some extent. Audiobooks are already in situ. Digital libraries have brought literature—written and oral—onto our laps. Digital Humanities is growing as a discipline. Corpus and computational linguistics are turning literary critics into positivists. Quantification is being normalized in literary studies. The availability of high-quality recording gadgets, high-speed uploading, dynamic websites, cloud storage, social-media networks etc. leaves us with no excuse. It is time to compute our languages and digitize our folk literature.

Under a Higher Education Commission (HEC) sponsored project “Digitizing Folk Wisdom: A project of collection, translation and study of folk literature in major Pakistani languages,” we are working on identifying and introducing folk literary genres, and collecting, transcribing, translating and digitizing pieces from these genres coming from seven Pakistani languages (Balochi, Brahui, Pashto, Punjabi, Saraiki, Sindhi and Urdu) in the first phase. Alert to the changing needs of the time, we are working, conscious of the fact that staying in contact with our past is significant, as a better sense of our heritage helps us better understand why we are where we are today. We are here—exactly where you are reading this article, reading my lament over our absence from an Internet space which is over-showcasing the global. It is a global that is disproportionate. This new world (dis)order calls for action.

Join hands!