When we got married in 1999, my husband was posted in Quetta. We were based on Zarghun Road, the erstwhile Railway Accounts Academy. It was built by the British in 1887. So, we had the privilege to inhabit the bungalow, which had been vacant for years. I remember cleaning it up with Aziz Chacha and screaming with fear as lizards – the size of my forearm and as fat as pigs – fell off the curtains, which we were removing so as to send them to the laundry and replacing them with new ones. Aziz Chacha claimed I was brave and bold. Though I still think I was the opposite.

I vividly remember our maali (gardener), who was much too fond of planting poppies. He would let the flowers dry and take the bulbs, which, I learned later, were used to make opium. Sometimes he would give me poppy seeds, as he knew I used them in cooking and baking. Maali Baba also made qehwa (tea without milk) with the poppy bulb when I developed bronchitis in December – our second month in Quetta’s cold, harsh winters – educating me about its herbal remedies. The tea has intoxicating effects, which ultimately help cure a severe cough. The cough is synonymous with the dryness and smoke hovering over the valley environment. Though in those days, hundreds of veteran teak and silver oaks trees were perched on the sidewalk of Zarghun Road and Thandi Sarak. Most of the birds which made their home in these trees have now migrated from Quetta and Hanna Lake to faraway lands. These oxygen purifiers are destroyed to make room for carbon-generating slayers of the modern age: i.e. automobiles and more.

My first train trip to Quetta from Karachi happened in March. We were in Karachi for Eid. The idea of travelling on a train seemed not only adventurous but also romantic to the then-hidden poet in me. A sleeper was booked, tickets purchased and dinner was packed for the night. My youngest brother was to accompany us not-so-newlyweds. All excited, we embarked on our journey to the provincial capital of Balochistan. Traveling in the Bolan mail from Karachi cantonment, via Dadu, Larkana, Sibbi, Mach and Kolpur station to finally Quetta was exactly a 22-hour journey. We were on time. The only thing I couldn’t figure out was the use of the train toilet. It made me think about the human scavengers cleaning the tracks, which is undoubtedly an honourable mention. This 921 km distance had sundown, a moon-lit, star-studded night, complete with rising to a glorious morning. We came across diverse land- and skyscapes. The Kojack Pass – the longest, most historic railway tunnel, was an experience I will never forget.

Karim Chacha’s okra and karahi is still etched in my taste buds. I learnt from him how to make okra, keeping it dry and green when served.

Fruits, vegetables and dry fruit blossom along the road to Urak. The heated noons of June were spent sitting on stones at Urak Fall, letting the cold water flow on me. The scent of sintrosa – a cross between apricots and plums – everything is still alive in my mind’s eye.

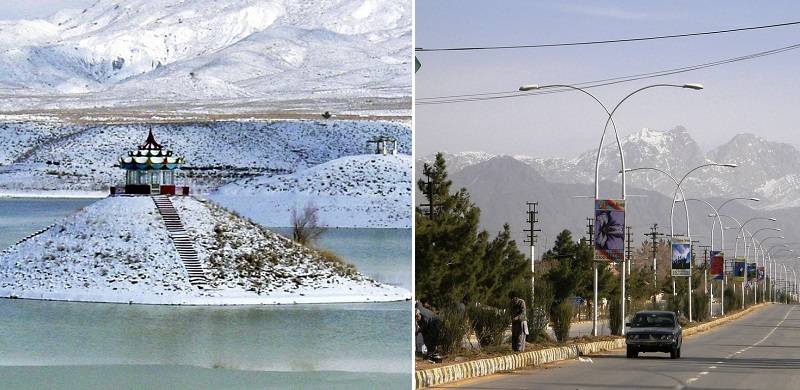

I remember everything with so much fondness. The Ziarat Residency, the walnut trees, getting my first fever from November’s chilling winds, finding the doctor and making lifelong family friends, playing cricket with them and their children at the Hanna Lake resort, the rugged beauty of our Balochistan, the mutton cooked in a deep hole in the ground, the customs and hospitality, the respect and traditions which are held tightly, and the deprived Baloch, Hazara and Brahui peoples, the mineral-rich mountains and their ever vibrantly, naturally coloured hues, the moon – which used to park on our boundary wall watching us look at it in awe all night, majnoon– the blood red maroon mulberry, the garlic sprouting in the kitchen garden and the scarlet ruby roses fencing the pathways and the entrance.

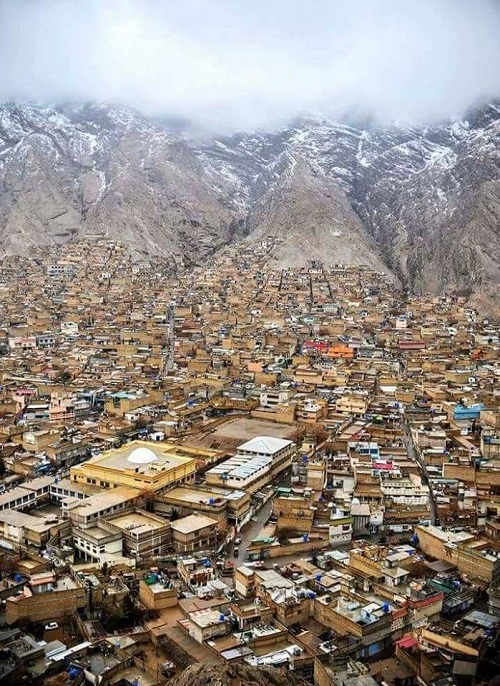

Every evening, wrapped in the traditional chaddar, my husband and I would take a walk on the Zarghun Road under the elegant conifers before evening tea. We were the only couple who walked there; it seemed then. Not that we were self-absorbed, but, in reality, we were. The traffic sergeant at the St Francis’ Grammar School junction would signal all four sides to stop and let us cross the roads with grace without mentioning it. What he didn’t realise, perhaps, was that his way of honouring us made its mark forever in our humbled hearts.

Quetta Serena had its own mysterious charm with its architecture and design. Quetta Serena amalgamates the mud exteriors and water channels typical of rural structures with trees, foliage, stone pathways, bubbling fountains and semi-covered external corridors to create a soothing and vernacular ambience. Apple trees along the water channels and breathtaking roses hanging on clear water are but a few images of heaven on earth. The serenity echoed the generosity and vastness of Balochistan.

I dream of sitting in a nook somewhere at Serena and sipping apple juice, sometimes, even now, in my seclusion. The interior was decorated with indigenous art and craft. The kilims, farshi baithak (traditional floor sitting), the back pillows, the local carpets, and the brightly coloured white sheets loudly applauded the sophistication and grace of the Baloch culture. Getting to know people around, our only neighbours, weekend dinners, and get-togethers are all wistfully painted in my mind. Playing badminton with the Pakistan national women’s team, and actually winning a game, made my adrenaline rush – I was quite proud!

We celebrated our first anniversary with all our friends. Even the qasab (butcher) Rab Nawaz – I can’t remember his full name – brought the best meat on one call.

Jinnah Road, Peach Melba, D’Souza’s chicken patties, the musty bookstores, restaurants where one would rarely find women in those days, the Quetta Arts Council, where I first met the artist Jamal Shah and another abstractionist – if I am not forgetting Naseeb Khan – and being the only female in the audience at a musical night in PNCA Quetta: I remember everything vividly.

Jinnah Road, Peach Melba, D’Souza’s chicken patties, the musty bookstores, restaurants where one would rarely find women in those days, the Quetta Arts Council, where I first met the artist Jamal Shah and another abstractionist – if I am not forgetting Naseeb Khan – and being the only female in the audience at a musical night in PNCA Quetta: I remember everything vividly.

But then some local traditions made me uncomfortable for a bit. Once when I went to open my account in a local bank with my Mamoo. The manager refused to address me directly and would only talk to Guddo Mama. As a Karachiite and a young student, I was unaware of these traditions and uncomfortable. These norms were later explained to me.

The tremendous hospitality and humility of the Baloch is a beautiful lesson in life. I had to visit again a year or two later to get my degree from Balochistan University. I was still not a parent then, and one of our acquaintances offered their newborn baby for adoption. That’s the highest degree of giving and respect that I was bestowed upon by another human in the short history of my being.

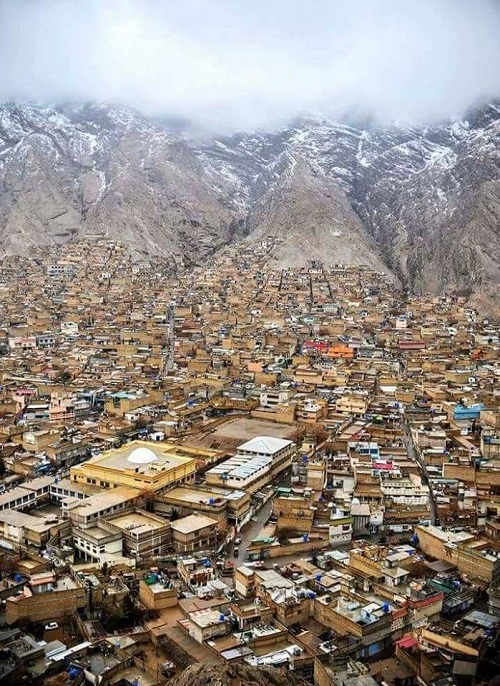

Quetta and its literati, the dove-white turbans, the wide shalwars that the Baloch don, the Buggtis and Jamalis, the smugglers, the businessmen, the embroidered dresses and chaddars, walk along the Zarghun Road, the Quetta cantonment, Chand Raat in the Cantonment, with friends, eating home-baked pizza with my first family friend, dipping toes in the water channel, sitting under the cool shade of the thick mulberry trees in mid-summer, ice cold showers in heated afternoons, being lonely and nostalgic for my parents and siblings during long workless days, inventing and discovering myself – all of these things are redolent of whom I am today.

Quetta, I miss your peace and cultural riches.

I vividly remember our maali (gardener), who was much too fond of planting poppies. He would let the flowers dry and take the bulbs, which, I learned later, were used to make opium. Sometimes he would give me poppy seeds, as he knew I used them in cooking and baking. Maali Baba also made qehwa (tea without milk) with the poppy bulb when I developed bronchitis in December – our second month in Quetta’s cold, harsh winters – educating me about its herbal remedies. The tea has intoxicating effects, which ultimately help cure a severe cough. The cough is synonymous with the dryness and smoke hovering over the valley environment. Though in those days, hundreds of veteran teak and silver oaks trees were perched on the sidewalk of Zarghun Road and Thandi Sarak. Most of the birds which made their home in these trees have now migrated from Quetta and Hanna Lake to faraway lands. These oxygen purifiers are destroyed to make room for carbon-generating slayers of the modern age: i.e. automobiles and more.

My first train trip to Quetta from Karachi happened in March. We were in Karachi for Eid. The idea of travelling on a train seemed not only adventurous but also romantic to the then-hidden poet in me. A sleeper was booked, tickets purchased and dinner was packed for the night. My youngest brother was to accompany us not-so-newlyweds. All excited, we embarked on our journey to the provincial capital of Balochistan. Traveling in the Bolan mail from Karachi cantonment, via Dadu, Larkana, Sibbi, Mach and Kolpur station to finally Quetta was exactly a 22-hour journey. We were on time. The only thing I couldn’t figure out was the use of the train toilet. It made me think about the human scavengers cleaning the tracks, which is undoubtedly an honourable mention. This 921 km distance had sundown, a moon-lit, star-studded night, complete with rising to a glorious morning. We came across diverse land- and skyscapes. The Kojack Pass – the longest, most historic railway tunnel, was an experience I will never forget.

The kilims, farshi baithak (traditional floor sitting), the back pillows, the local carpets, and the brightly coloured white sheets loudly applauded the sophistication and grace of the Baloch culture

Karim Chacha’s okra and karahi is still etched in my taste buds. I learnt from him how to make okra, keeping it dry and green when served.

Fruits, vegetables and dry fruit blossom along the road to Urak. The heated noons of June were spent sitting on stones at Urak Fall, letting the cold water flow on me. The scent of sintrosa – a cross between apricots and plums – everything is still alive in my mind’s eye.

I remember everything with so much fondness. The Ziarat Residency, the walnut trees, getting my first fever from November’s chilling winds, finding the doctor and making lifelong family friends, playing cricket with them and their children at the Hanna Lake resort, the rugged beauty of our Balochistan, the mutton cooked in a deep hole in the ground, the customs and hospitality, the respect and traditions which are held tightly, and the deprived Baloch, Hazara and Brahui peoples, the mineral-rich mountains and their ever vibrantly, naturally coloured hues, the moon – which used to park on our boundary wall watching us look at it in awe all night, majnoon– the blood red maroon mulberry, the garlic sprouting in the kitchen garden and the scarlet ruby roses fencing the pathways and the entrance.

Every evening, wrapped in the traditional chaddar, my husband and I would take a walk on the Zarghun Road under the elegant conifers before evening tea. We were the only couple who walked there; it seemed then. Not that we were self-absorbed, but, in reality, we were. The traffic sergeant at the St Francis’ Grammar School junction would signal all four sides to stop and let us cross the roads with grace without mentioning it. What he didn’t realise, perhaps, was that his way of honouring us made its mark forever in our humbled hearts.

Quetta Serena had its own mysterious charm with its architecture and design. Quetta Serena amalgamates the mud exteriors and water channels typical of rural structures with trees, foliage, stone pathways, bubbling fountains and semi-covered external corridors to create a soothing and vernacular ambience. Apple trees along the water channels and breathtaking roses hanging on clear water are but a few images of heaven on earth. The serenity echoed the generosity and vastness of Balochistan.

I dream of sitting in a nook somewhere at Serena and sipping apple juice, sometimes, even now, in my seclusion. The interior was decorated with indigenous art and craft. The kilims, farshi baithak (traditional floor sitting), the back pillows, the local carpets, and the brightly coloured white sheets loudly applauded the sophistication and grace of the Baloch culture. Getting to know people around, our only neighbours, weekend dinners, and get-togethers are all wistfully painted in my mind. Playing badminton with the Pakistan national women’s team, and actually winning a game, made my adrenaline rush – I was quite proud!

We celebrated our first anniversary with all our friends. Even the qasab (butcher) Rab Nawaz – I can’t remember his full name – brought the best meat on one call.

Jinnah Road, Peach Melba, D’Souza’s chicken patties, the musty bookstores, restaurants where one would rarely find women in those days, the Quetta Arts Council, where I first met the artist Jamal Shah and another abstractionist – if I am not forgetting Naseeb Khan – and being the only female in the audience at a musical night in PNCA Quetta: I remember everything vividly.

Jinnah Road, Peach Melba, D’Souza’s chicken patties, the musty bookstores, restaurants where one would rarely find women in those days, the Quetta Arts Council, where I first met the artist Jamal Shah and another abstractionist – if I am not forgetting Naseeb Khan – and being the only female in the audience at a musical night in PNCA Quetta: I remember everything vividly.But then some local traditions made me uncomfortable for a bit. Once when I went to open my account in a local bank with my Mamoo. The manager refused to address me directly and would only talk to Guddo Mama. As a Karachiite and a young student, I was unaware of these traditions and uncomfortable. These norms were later explained to me.

The tremendous hospitality and humility of the Baloch is a beautiful lesson in life. I had to visit again a year or two later to get my degree from Balochistan University. I was still not a parent then, and one of our acquaintances offered their newborn baby for adoption. That’s the highest degree of giving and respect that I was bestowed upon by another human in the short history of my being.

Quetta and its literati, the dove-white turbans, the wide shalwars that the Baloch don, the Buggtis and Jamalis, the smugglers, the businessmen, the embroidered dresses and chaddars, walk along the Zarghun Road, the Quetta cantonment, Chand Raat in the Cantonment, with friends, eating home-baked pizza with my first family friend, dipping toes in the water channel, sitting under the cool shade of the thick mulberry trees in mid-summer, ice cold showers in heated afternoons, being lonely and nostalgic for my parents and siblings during long workless days, inventing and discovering myself – all of these things are redolent of whom I am today.

Quetta, I miss your peace and cultural riches.