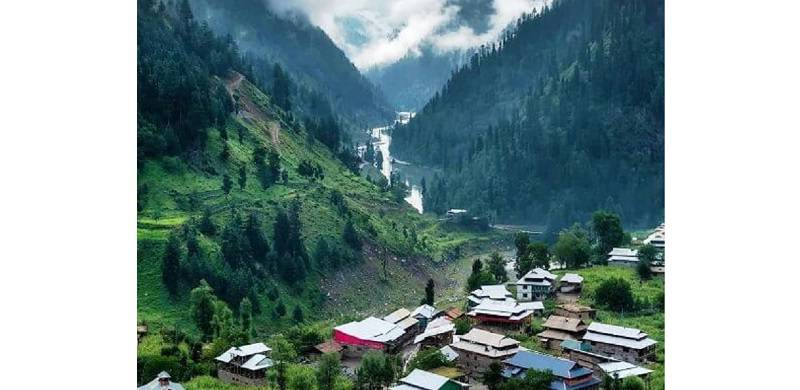

There was once a beautiful lake called Karewa Lake. After a tectonic shift in the Earth’s crust, Karewa lake birthed a valley more beautiful than anything ever seen. It was Kashmir. In all its glory, its verdancy knew no bounds. I had heard many call it a “Paradise on Earth” but as I stood amongst the tall trees of deodar, pine and fir that enveloped the valley, I felt as if I was the first person to behold the Garden of Eden. The cup of chai that I ordered at the resort sat forgotten at the rickety wooden table in front of me. I stared open-mouthed at the untamed beauty around me. I felt as if I was in a trance. The October sun baked the mountain tops, and the trees were just beginning to turn the entire valley into the colour of a ripe orange. Nestled between the Karakoram Range and the Pir Panjal, Kashmir called out to hundreds of restless souls to seek refuge under its formidable mountains, covered with a sheet of thick, green forests. I arrived at Keran. A picturesque little village sliced in half by the river Neelum. Tucked between the towering hills of the valley, Keran sits at the Line of Control, which is a boundary that divides Jammu and Kashmir. My resort was a fascinating little spot where I could see the Indian-occupied part of the valley. It was an absurd thing to think about that the mountains on the other side of Neelum and half its waters were ‘theirs’ and half of it was ‘ours’. As if such divine beauty could ever be divided by human intervention!

Upon my arrival at Keran, the very first thing I did was to drop my bags in the dingy, rented room of the resort. The room had a plush, red carpet with soft cushions which smelled of the pine cones that were dropped from its trees to scatter all around the hill. After locking the door behind me with a shabby set of keys I got from the front desk, I descended the stone steps of the hill the resort was built on and made my way down to the rocky bank of the river.

I chose a sturdy-looking boulder to sit on and took off my shoes to dip my feet in the cold water. That is when I noticed a movement at the opposite side of the river. It was a woman dressed in a simple shalwar kurta and a dupatta on her head. She came down the muddy mountain path with a cat-like grace from the opposite side of the river. Her lithe form jumped from one rock to another with an ease that only comes from years of practice. In one hand, she held a pot made of clay and in the other, a rope. I followed the rope with my eyes, and to my surprise, found an ominous looking bull tethered to the other end of it. With the tips of his crescent-like horns reflecting the sunlight in just the right way, the beast looked majestic. The woman hunched up her shalwar and squatted on a nearby boulder and began filling the clay pot with the cool, refreshing water. The bull dipped his head and nudged the river water with his quivering nose, but before he could drink, I found his empty, black eyes staring directly at me as if finally sensing that he was being watched. He tipped his head to the side, the movement causing his horn to slash the face of the river. The woman noticed the bull’s restlessness and whispered something to him which had quite a soothing effect on him. Done talking to the animal, she looked accusingly at me. As Neelum crashed against the boulders embedded in the river between us, all I could do was wave at her. She didn’t wave back but kept looking at me with her head tipped to one side, reminding me of the beast by her side. I gathered my things: a pen and a notebook, some flowers I had snipped from the courtyard of the resort to put in my notebook, and a small collection of rocks I had found by the riverbank, their surfaces polished and smoothened by the force of its waters. I haphazardly shoved my belongings into my backpack and made my way back up to the resort for breakfast.

The smell of fried onions wafted to the courtyard through the adjoining kitchen area. I sat facing the mountain that did not belong to us, taking in the glorious morning. I was occupied with the thoughts of the woman I had just seen, when I was interrupted by a male voice from behind me. It was the man who had given me the keys to my room. His salt-and-pepper hair made him look like he was in his late forties. He wore a light blue sweater over his shalwar kameez and his bushy moustache quivered under his breath.

“You shouldn’t make contact with the people from the other side. I saw you earlier. It’s not safe,” he declared.

“I’m sure no one saw. I was alone by the river.” I said apologetically.

“Here, there are eyes everywhere,” He pointed upwards to the part of the hill called Upper Keran.

“Have you ever crossed the river, Chacha?” I asked him after a beat.

I realised too late that I had offended him. He shifted his weight on both feet and puffed up his chest.

“Never. I’m not crazy. Those people are not our friends. And there is a chance that you might get fired upon if they suspect you of spying for the other side,” he replied while looking up at the hill again.

I stared at him stupidly while I processed what he had just said. After regaining my composure, I scanned the towering hills around me anxiously. Surely, there is no one holding a gun and a pair of binoculars atop these hills?

“Don’t go to the riverbank again. And don’t wave to anyone from the other side,” he left after a warning glance at me.

I tried to shake off the feeling of being perceived rather unsuccessfully. The paranoia followed me around the entire day.

At night, Keran was bathed in darkness. The only source of light was that of the full moon hanging low in the mountains. As I sat in the courtyard overlooking the moonlit Neelum, I decided that tomorrow, I would go as far up as I could into Upper Keran and see what it was all about.

The next morning, I made my way up to Upper Keran. Far from Lahore, the smog capital of the country, I took a deep breath and let my lungs inflate with the sweet scents emanating from the wilderness around me. I trudged past thick branches of trees sprawled across the hill and the unpredictable, stony pathway to the top of the hill. I could hear a symphony of birds chirping around the forest looking for food. As I searched for the perfect spot to stop and rest, I passed by all sorts of people. I could tell apart the locals and the tourists by the agility of their movements as they went up and down the hill. I was soon breathless with the ascent and tired of firmly placing my foot into the muddy path. My attention was caught by the children from the village sprinting past me in a game they were playing. Were they aware of the chirping birds, the rustling of the leaves, and the whooshing sound of the mountain peaks cutting through the wind? Were they aware of their own fragility in the rocky terrain of the valley? Or was it just home to them?

These thoughts followed me as I made my way to a chunk of rock jutting out of the hill. I grabbed the nearby branches of a tree to steady myself as I hunched over to sit beneath it. I took out my pencil and my notebook and began sketching the scenic beauty before me so I could paint it later. I made some notes of the way sunlight fell on the hills opposite me and the way it twinkled when it touched the splashing water of the river. So engrossed in my drawing, it took me a while to feel a presence behind me. I slowly turned to look and found a young girl who looked about sixteen watching me curiously. She carried a school bag on her shoulder and wore white bangles up to her elbows and a pair of silver jhumkay adorned her ears. She looked like a resident of the village who was on her way home from school.

“Are you drawing their hills?” she pointed towards the Indian-held Kashmir. “Yes. Because those are the only ones I can see from here,” I smiled at her.

“So wouldn’t it make them ‘our’ hills since our side is the only one that can see them?” she giggled.

I didn’t have an answer for her at that moment. Instead, I asked, “Do you ever wonder what the other side is like?”

“I think it’s all the same. How could it be different? It’s all home,” she replied.

“My uncle did try to cross the river once. That was before I was born. I have three uncles, one of them, the oldest one, lived there.” She pointed towards the hill opposite us. “He didn’t make it back, my uncle. My father told me that he drowned while trying to get there,” she added.

Before I could say anything, she spoke again, “But I think it’s just a story my father made up so I wouldn’t go too close to the river!” She shrugged.

After the girl left, I sat there for a long time. I kept mulling over what she had said. Dusk was falling. The sun was swallowed by the mountains behind me and soon, the entire valley was bathed in the moonlight. The river below me sparkled and the tides roared with the pull of the full moon. This spot was the closest you could get to the boundary between India and Pakistan. The glittering waters of Neelum were a thing of purity in spite of everything they had stood witness to. It was as if Poseidon himself had taken the responsibility of looking over Neelum as it had not only withstood the valley’s bloody history after the division of the Subcontinent, but also the haunting cries of the families split by the divide on either side of Keran. And yet, still it had remained invulnerable, untouched by the chaos of human life.

For decades, people have stood at the bank of the river, staring longingly at the other side, longing for the other half of their family, the other half of their sanctuary. It was surreal how in this quaint little village where so much pain, paranoia and longing resided in the hearts of its inhabitants, hundreds like me came rushing to find peace. For me, Kashmir was a beautiful, breath-taking tragedy; For its dwellers, it was all home.

Upon my arrival at Keran, the very first thing I did was to drop my bags in the dingy, rented room of the resort. The room had a plush, red carpet with soft cushions which smelled of the pine cones that were dropped from its trees to scatter all around the hill. After locking the door behind me with a shabby set of keys I got from the front desk, I descended the stone steps of the hill the resort was built on and made my way down to the rocky bank of the river.

“Never. I’m not crazy. Those people are not our friends. And there is a chance that you might get fired upon if they suspect you of spying for the other side,” he replied while looking up at the hill again

I chose a sturdy-looking boulder to sit on and took off my shoes to dip my feet in the cold water. That is when I noticed a movement at the opposite side of the river. It was a woman dressed in a simple shalwar kurta and a dupatta on her head. She came down the muddy mountain path with a cat-like grace from the opposite side of the river. Her lithe form jumped from one rock to another with an ease that only comes from years of practice. In one hand, she held a pot made of clay and in the other, a rope. I followed the rope with my eyes, and to my surprise, found an ominous looking bull tethered to the other end of it. With the tips of his crescent-like horns reflecting the sunlight in just the right way, the beast looked majestic. The woman hunched up her shalwar and squatted on a nearby boulder and began filling the clay pot with the cool, refreshing water. The bull dipped his head and nudged the river water with his quivering nose, but before he could drink, I found his empty, black eyes staring directly at me as if finally sensing that he was being watched. He tipped his head to the side, the movement causing his horn to slash the face of the river. The woman noticed the bull’s restlessness and whispered something to him which had quite a soothing effect on him. Done talking to the animal, she looked accusingly at me. As Neelum crashed against the boulders embedded in the river between us, all I could do was wave at her. She didn’t wave back but kept looking at me with her head tipped to one side, reminding me of the beast by her side. I gathered my things: a pen and a notebook, some flowers I had snipped from the courtyard of the resort to put in my notebook, and a small collection of rocks I had found by the riverbank, their surfaces polished and smoothened by the force of its waters. I haphazardly shoved my belongings into my backpack and made my way back up to the resort for breakfast.

The smell of fried onions wafted to the courtyard through the adjoining kitchen area. I sat facing the mountain that did not belong to us, taking in the glorious morning. I was occupied with the thoughts of the woman I had just seen, when I was interrupted by a male voice from behind me. It was the man who had given me the keys to my room. His salt-and-pepper hair made him look like he was in his late forties. He wore a light blue sweater over his shalwar kameez and his bushy moustache quivered under his breath.

“You shouldn’t make contact with the people from the other side. I saw you earlier. It’s not safe,” he declared.

“I’m sure no one saw. I was alone by the river.” I said apologetically.

“Here, there are eyes everywhere,” He pointed upwards to the part of the hill called Upper Keran.

“Have you ever crossed the river, Chacha?” I asked him after a beat.

I realised too late that I had offended him. He shifted his weight on both feet and puffed up his chest.

“Never. I’m not crazy. Those people are not our friends. And there is a chance that you might get fired upon if they suspect you of spying for the other side,” he replied while looking up at the hill again.

I stared at him stupidly while I processed what he had just said. After regaining my composure, I scanned the towering hills around me anxiously. Surely, there is no one holding a gun and a pair of binoculars atop these hills?

“Don’t go to the riverbank again. And don’t wave to anyone from the other side,” he left after a warning glance at me.

I tried to shake off the feeling of being perceived rather unsuccessfully. The paranoia followed me around the entire day.

At night, Keran was bathed in darkness. The only source of light was that of the full moon hanging low in the mountains. As I sat in the courtyard overlooking the moonlit Neelum, I decided that tomorrow, I would go as far up as I could into Upper Keran and see what it was all about.

The next morning, I made my way up to Upper Keran. Far from Lahore, the smog capital of the country, I took a deep breath and let my lungs inflate with the sweet scents emanating from the wilderness around me. I trudged past thick branches of trees sprawled across the hill and the unpredictable, stony pathway to the top of the hill. I could hear a symphony of birds chirping around the forest looking for food. As I searched for the perfect spot to stop and rest, I passed by all sorts of people. I could tell apart the locals and the tourists by the agility of their movements as they went up and down the hill. I was soon breathless with the ascent and tired of firmly placing my foot into the muddy path. My attention was caught by the children from the village sprinting past me in a game they were playing. Were they aware of the chirping birds, the rustling of the leaves, and the whooshing sound of the mountain peaks cutting through the wind? Were they aware of their own fragility in the rocky terrain of the valley? Or was it just home to them?

These thoughts followed me as I made my way to a chunk of rock jutting out of the hill. I grabbed the nearby branches of a tree to steady myself as I hunched over to sit beneath it. I took out my pencil and my notebook and began sketching the scenic beauty before me so I could paint it later. I made some notes of the way sunlight fell on the hills opposite me and the way it twinkled when it touched the splashing water of the river. So engrossed in my drawing, it took me a while to feel a presence behind me. I slowly turned to look and found a young girl who looked about sixteen watching me curiously. She carried a school bag on her shoulder and wore white bangles up to her elbows and a pair of silver jhumkay adorned her ears. She looked like a resident of the village who was on her way home from school.

“Are you drawing their hills?” she pointed towards the Indian-held Kashmir. “Yes. Because those are the only ones I can see from here,” I smiled at her.

“So wouldn’t it make them ‘our’ hills since our side is the only one that can see them?” she giggled.

I didn’t have an answer for her at that moment. Instead, I asked, “Do you ever wonder what the other side is like?”

“I think it’s all the same. How could it be different? It’s all home,” she replied.

“My uncle did try to cross the river once. That was before I was born. I have three uncles, one of them, the oldest one, lived there.” She pointed towards the hill opposite us. “He didn’t make it back, my uncle. My father told me that he drowned while trying to get there,” she added.

Before I could say anything, she spoke again, “But I think it’s just a story my father made up so I wouldn’t go too close to the river!” She shrugged.

After the girl left, I sat there for a long time. I kept mulling over what she had said. Dusk was falling. The sun was swallowed by the mountains behind me and soon, the entire valley was bathed in the moonlight. The river below me sparkled and the tides roared with the pull of the full moon. This spot was the closest you could get to the boundary between India and Pakistan. The glittering waters of Neelum were a thing of purity in spite of everything they had stood witness to. It was as if Poseidon himself had taken the responsibility of looking over Neelum as it had not only withstood the valley’s bloody history after the division of the Subcontinent, but also the haunting cries of the families split by the divide on either side of Keran. And yet, still it had remained invulnerable, untouched by the chaos of human life.

For decades, people have stood at the bank of the river, staring longingly at the other side, longing for the other half of their family, the other half of their sanctuary. It was surreal how in this quaint little village where so much pain, paranoia and longing resided in the hearts of its inhabitants, hundreds like me came rushing to find peace. For me, Kashmir was a beautiful, breath-taking tragedy; For its dwellers, it was all home.