The fate of immigrants to another country is always fraught with uncertainties and doubts. Still moving from one part of the world to another – often an alien-looking world – has been the story of mankind. It is not easy to leave everything familiar and comforting behind and strike out in a new land.

In August of 1963, when I boarded an Alitalia airplane in Karachi for my onward journey to the United States, I carried a small suitcase of clothes and few of my favourite books. I also carried a rich album of cherished memories with me.

As is the experience of most immigrants, the first year was extremely hard. Away from familiar and soothing surroundings, I missed the sounds and smells of the streets and alleys of Peshawar. The subtle smoke of fresh bread permeating the neighbourhood arising from Lali’s underground clay oven, the tandoor, would be just one example.

And I missed the early morning music wafting over the neighbourhood coming from a radio tuned to Radio Ceylon. That and much more was enough to bring tears to my eyes and yes, I cried a lot and wondered if the dislocation was necessary for my peace of mind. I also knew that in the balance hung my future as a cardiovascular surgeon.

For the entire year of internship, I kept mainly to myself, seldom socialised and concentrated on my work. Recorded desi music and Urdu books of fiction were my refuge.

During a 1993 meeting with Yusaf Khan aka Dilip Kumar in Toronto, I presented him a set of these maps. He was ecstatic and wanted me to point out his neighbourhood on the map. I walked him on the map from Kabuli Gate to his neighbourhood of Mohalla Khuda Dad

During that difficult period, I started recalling parts of my hometown; the labyrinthine alleys of the walled city of Peshawar. I would plan a route from our home to a particular destination within the city. That in turn led to pen and paper where I would draw the rout to homes of our relatives, my high school and other destinations.

Peshawar is an ancient town and the oldest living city in Asia. its roots go back to 400 years before the Common Era. Wave after wave of invaders either from across the western Hindu Kush Mountains or from the plains of India came to the region to loot and pilfer. Each one left indelible mark on the city.

Until 1960, Peshawar city was a majority Hindko-speaking city and that language-based culture prevailed within its walls. Finding myself in the US now, I had ample opportunities to speak Urdu, some opportunities to speak Pashto – but none to speak Hindko.

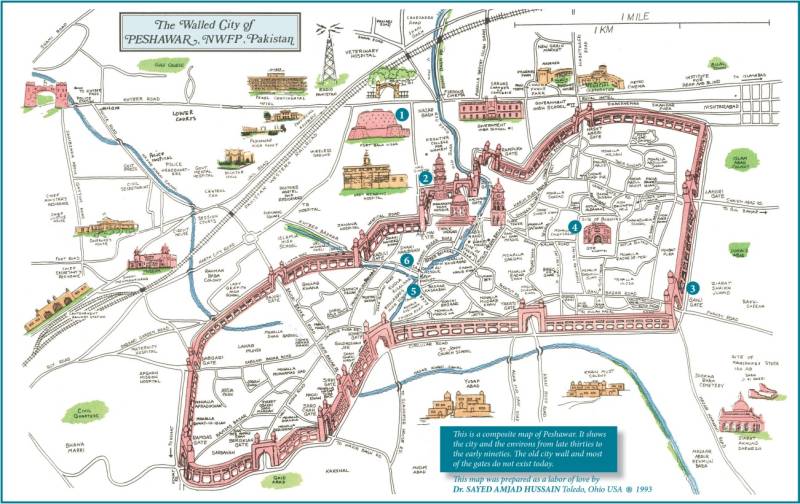

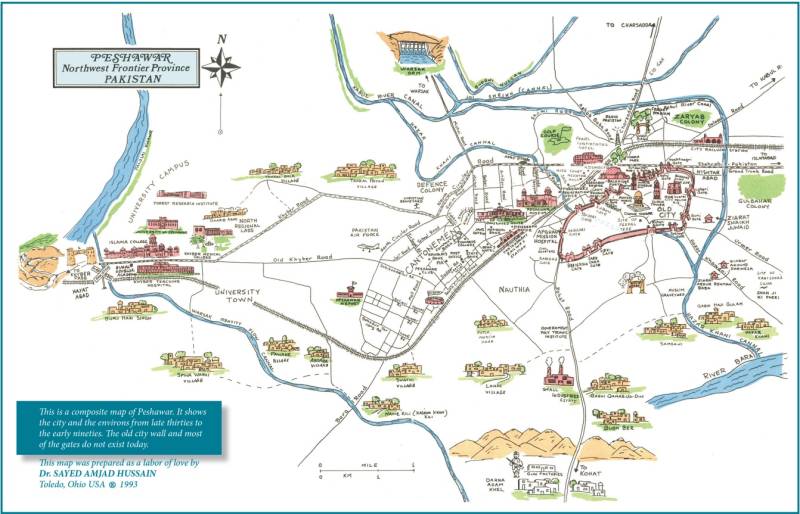

It took many years to overcome the pain of separation. But still the flood of memories was there, waiting to cascade with the slightest of a trigger. It was during one of those melancholic moods that I decided to collate and put together my non-artistic doodling of various parts of Peshawar that had been my favourite past time in my early years in America. Now I am not a cartographer or mapmaker in any sense of the word. But I did try. And within a few months, mostly from my memory, I drew a map of the city and surrounding area. I sought help from a novice artist to draw, in black ink, various landmarks in and around Peshawar to enhance the map. Once some colour was splashed, it looked good. I was satisfied with the result and went ahead and had a few dozen copies printed.

I sent the map to select Peshawari friends. One friend, the late Johar Mir who lived in New York City, a poet and writer par excellence, wrote back immediately to complain. People who are born and raised within the old city have certain possessiveness about their town. Hence when they see something amiss, they don’t hesitate to point it out.

Johar Mir was perturbed that I had, instead of drawing a detailed map of the old city, delegated the city to relative obscurity by showing it a small, albeit a very small part of the whole metropolitan area. To him, the old city was the real identity of Peshawar, not the cantonment, not the suburbs and not the glittering shopping plazas. And as if to drive the point home, he asked rhetorically, "Where do you suppose I would find my neighbourhood in this tiny patch and to look for Lali’s tandoor (bakery) and the shop of Chacha Hakimo pansari?"

He certainly had a point. So, I embarked upon drawing an exclusive map of the walled city.

In my childhood, in the 1940s, the old city was still hemmed in within a wall, and had 17 gates that were closed at sunset and reopened at the crack of dawn. In the 1950 some gates came down and the city started spilling out in the surrounding areas. For the map I decided that I will show the city with the wall and gates as I had known it in my early life.

It took a hard work and lots of love to complete the project.

As was the custom, the British while ruling India built garrison towns or cantonments a short distance from the old cities. Naturally they gave British names to neighbourhoods and streets. They did the same in the old cities but to a much lesser extent. The neighbourhoods in Peshawar continued to be identified by their ancient names. In fact, HG Raverty, an Englishman traveling through the area in 1852 left a detailed description of the city, its demographics and the various neighbourhoods. His passage through Peshawar was decades before the British established a foothold on the Frontier.

Peshawaris are peculiar in naming places in their own somewhat lazy and simplistic way. For example, there were many cinema houses just outside the old city. Naz Cinema on Kutchery Road was owned by Sikhs and even after the Partition it was commonly called the Cinema of the Sikhs (Sikha'N Wali Bioscope). Incidentally around 1900 a movie projector was called bioscope. By common usage the places where the projectors were used were also called bioscopes.

There were three cinemas in a row just outside the western wall of the city. They had names: Novelty Talkies, Tasveer Mahal, and Picture House. Peshawaris however called them the near one (to the city) the middle one and the farthest one. In Hindko they were commonly referred to as Urli, Wichkarli and Parli bioscopes.

During a 1993 meeting with Yusaf Khan aka Dilip Kumar in Toronto, I presented him a set of these maps. He was ecstatic and wanted me to point out his neighbourhood on the map. I walked him on the map from Kabuli Gate to his neighbourhood of Mohalla Khuda Dad. He looked at the row of cinemas outside Kabuli Gate and started laughing by reading the names that Peshawaris had given them. The map triggered a flood of memories for him and for better part of an hour he talked about his childhood in Mohalla Khuda Dad.

In 2005 I received an email from the Indian author Sanjit Narwekar who was in the process of writing a biography of Dilip Kumar. He wondered if could reproduce my map of the old city in his book. The map appeared in his 2006 book Dilip Kumar: The Last Emperor.

What started as an exercise to overcome my loneliness and homesickness in America turned into a document to record and preserve the memories of a city that so many of us have loved and cherished.

Today the same set of two maps hangs in the Governor's House, the headquarters of the Frontier Constabulary in Balahisar Fort and in countless homes in Peshawar and Diaspora. One hotel in Peshawar has a large mural of the map in the lobby. It has also appeared in a dozen or so books about Peshawar and appears in dozen or so books on Peshawar. The map of the old city has also been turned into a walking tour of the city and used by the provincial tourist department in its promotional literature.

On my annual visits to Peshawar, I often go for an early morning walk through the city. One time while going through a relatively unfamiliar part of the city, I got lost. It took me a while to get my bearings and get back on track. When I got home, I told my wife about getting lost in the city. She smiled and said that she knows someone who has drawn a detailed map of the city. On my next walk, she said, I ought to take that map with me.