On a pleasant fall day in October of 1999 a few friends and I took up on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington DC, in front of the Pakistan Embassy with placards in our hands.

“Go Home General,” said one.

“Honk for Democracy,” said another.

Whether Washingtonians knew of the latest coup d’etat in Pakistan, orchestrated this time by General Musharraf, they are nothing if not staunch believers in democracy so we got many honks from passing cars. Pedestrians were amused by our five-member protest. A man who emerged from the embassy chuckled. After a while of doing this, we went home—but Musharraf stayed for nine years.

This protest had been organized by a Pakistani couple but after the first day they went out of town so I took over. I asked other Pakistani friends to join but they were either not interested or they supported Musharraf. It did not seem to matter to them that he had overthrown a democratically elected government. I was also baffled by the reaction in Pakistan. People had celebrated the ascension of yet another self-appointed saviour of the nation. Mithai was distributed, firecrackers shot up in neighborhoods across cities.

But not everyone was in favour of the dictator. My father, a retired army officer himself—one of the three brigadiers who had resigned in Lahore in 1977—and a strong believer in democracy was one of the few who were deeply disturbed by the coup. Years later, most of those who supported the general’s ascension to power would regret their position.

And here we are, eighteen years later and Musharraf refuses to disappear from the news, even though he is irrelevant to today’s politics in Pakistan. He has issued statements in support of Hafiz Saeed, and has praised the banned Lashkar-e-Taiba. Brazenly, in an interview, he suggested that it would be alright to suspend the constitution when the need arose, for the sake of the country. Most recently, he has called for an extended interim government to put the house in order as he puts it. All these prescriptions come, mind you, from an absconder who is wanted by the law in Pakistan.

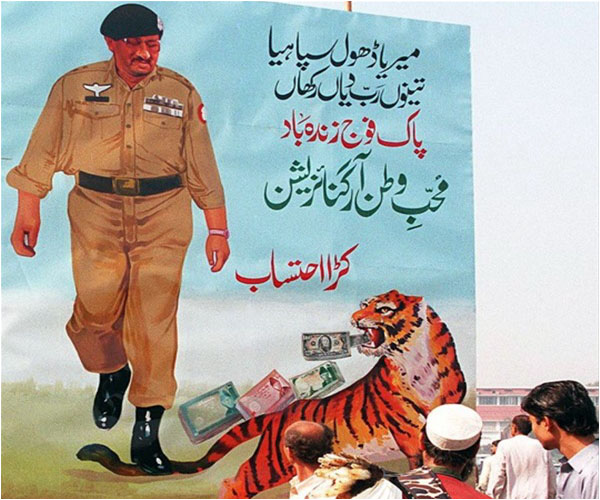

One of Musharraf’s problems was that he was an oxymoron: a weak dictator. While he was fond of comparing of himself to Kamal Ataturk of Turkey, and was a proponent of moderation, he wasn’t able to bring about any fundamental changes to Pakistan’s social fabric. More disappointingly, he shelved plans to reform the public school curriculum in order to appease right-wing religious parties. That has been the dilemma of dictators and political engineering forces in Pakistan; they can’t achieve their goals without the support of extreme ideological forces.

Since 1999, the world has changed in ways no one could have predicted. The world may have changed dramatically (and in many cases not always for the better), but Pakistan at least, seems to be going round in circles.

If only these well-televised ex-patriots stopped interfering in Pakistan’s affairs, and state institutions stopped encroaching on each other’s domains, and started doing their job, only their own job, could we begin to see political and social stability. Our holy man from Canada is already back in Pakistan, getting ready to save his old country again; but he’ll be sure to return to the comforts of Canada soon enough. Shouldn’t he at least be required to maintain residency in Pakistan for a minimum period, perhaps six months or a year in order to be allowed to stage protests that bring public life to a halt?

It is true that democracy take time to take root, but these roots are difficult to put down if growth is not allowed to continue. This would only be possible if all institutions believed that a strong political set-up is in the nation’s greater interest.

Not a lot of people know about our little protest in 1999, and many would have thought it made no difference, but I believe in what Margaret Mead said: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world; indeed it’s the only thing that ever has.” There were five of us on that autumn day in 1999: I, a Brit, an Indian, a South African, and an American.

There are those who are happy with political instability in Pakistan, seeing in it their own interest, and many would celebrate the installation of a prolonged technocrat government and would distribute mithai. But I believe that the majority of Pakistanis would oppose such an outcome. As for me and my friends, we still stand with democracy and the only government acceptable to us would be one that came about as a result of free and fair general elections, on schedule in 2018.

“Go Home General,” said one.

“Honk for Democracy,” said another.

Whether Washingtonians knew of the latest coup d’etat in Pakistan, orchestrated this time by General Musharraf, they are nothing if not staunch believers in democracy so we got many honks from passing cars. Pedestrians were amused by our five-member protest. A man who emerged from the embassy chuckled. After a while of doing this, we went home—but Musharraf stayed for nine years.

This protest had been organized by a Pakistani couple but after the first day they went out of town so I took over. I asked other Pakistani friends to join but they were either not interested or they supported Musharraf. It did not seem to matter to them that he had overthrown a democratically elected government. I was also baffled by the reaction in Pakistan. People had celebrated the ascension of yet another self-appointed saviour of the nation. Mithai was distributed, firecrackers shot up in neighborhoods across cities.

In 1999, I was baffled by the reaction in Pakistan to Musharraf's coup. People had celebrated the ascension of yet another self-appointed saviour of the nation

But not everyone was in favour of the dictator. My father, a retired army officer himself—one of the three brigadiers who had resigned in Lahore in 1977—and a strong believer in democracy was one of the few who were deeply disturbed by the coup. Years later, most of those who supported the general’s ascension to power would regret their position.

And here we are, eighteen years later and Musharraf refuses to disappear from the news, even though he is irrelevant to today’s politics in Pakistan. He has issued statements in support of Hafiz Saeed, and has praised the banned Lashkar-e-Taiba. Brazenly, in an interview, he suggested that it would be alright to suspend the constitution when the need arose, for the sake of the country. Most recently, he has called for an extended interim government to put the house in order as he puts it. All these prescriptions come, mind you, from an absconder who is wanted by the law in Pakistan.

One of Musharraf’s problems was that he was an oxymoron: a weak dictator. While he was fond of comparing of himself to Kamal Ataturk of Turkey, and was a proponent of moderation, he wasn’t able to bring about any fundamental changes to Pakistan’s social fabric. More disappointingly, he shelved plans to reform the public school curriculum in order to appease right-wing religious parties. That has been the dilemma of dictators and political engineering forces in Pakistan; they can’t achieve their goals without the support of extreme ideological forces.

Since 1999, the world has changed in ways no one could have predicted. The world may have changed dramatically (and in many cases not always for the better), but Pakistan at least, seems to be going round in circles.

If only these well-televised ex-patriots stopped interfering in Pakistan’s affairs, and state institutions stopped encroaching on each other’s domains, and started doing their job, only their own job, could we begin to see political and social stability. Our holy man from Canada is already back in Pakistan, getting ready to save his old country again; but he’ll be sure to return to the comforts of Canada soon enough. Shouldn’t he at least be required to maintain residency in Pakistan for a minimum period, perhaps six months or a year in order to be allowed to stage protests that bring public life to a halt?

It is true that democracy take time to take root, but these roots are difficult to put down if growth is not allowed to continue. This would only be possible if all institutions believed that a strong political set-up is in the nation’s greater interest.

Not a lot of people know about our little protest in 1999, and many would have thought it made no difference, but I believe in what Margaret Mead said: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world; indeed it’s the only thing that ever has.” There were five of us on that autumn day in 1999: I, a Brit, an Indian, a South African, and an American.

There are those who are happy with political instability in Pakistan, seeing in it their own interest, and many would celebrate the installation of a prolonged technocrat government and would distribute mithai. But I believe that the majority of Pakistanis would oppose such an outcome. As for me and my friends, we still stand with democracy and the only government acceptable to us would be one that came about as a result of free and fair general elections, on schedule in 2018.