It takes an exceptional circumstance for the women of Thar to camp out with men from other tribal communities. But outside the Islamkot press club these divisive traditions have taken a backseat for a unifying cause: to protest the Sindh government and a company’s joint decision to build a reservoir at Gorano to store what they say will be toxic water drained from coal mining. Take it some place else, they say.

Sita Bai, in her 30s, is one of those women, who is protesting with people from 12 villages around Gorano outside the press club. It is her 70th night there—a record not just for the length of the protest but also because the women have left their homes to do it. “It will inundate our entire area, which has been suffering a drought for many years,” she says, referring to their fears of the effect a reservoir will have on their ancestral village.

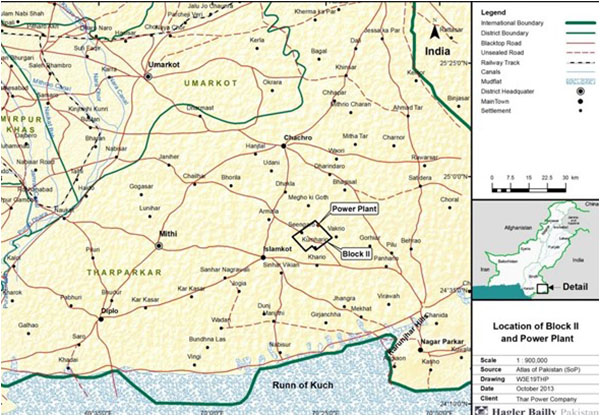

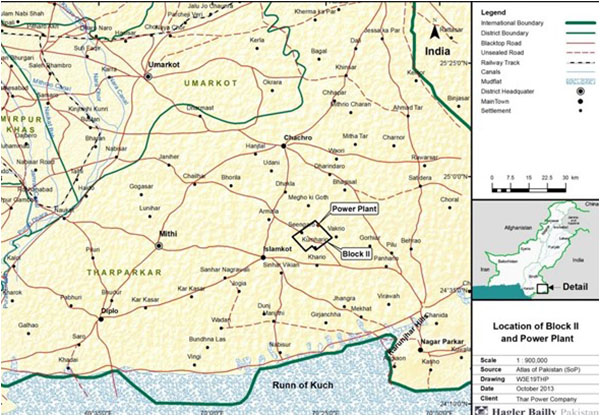

Sindh’s Thar desert, that lies along the Indian border, has reserves of around 175 billion tonnes of lignite coal. They have been divided into 12 blocks and the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC), a joint venture with the Sindh government, has started excavating in block 2. SECMC plans to excavate two billion tonnes of coal and build a 660 megawatt power plant, which is expected to send power to the national grid by June 2019. This is part of a bigger initiative as Thar’s coal excavation has been included in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Chinese are helping mine the reserves. The criticism has been that China is exporting its coal technology to Pakistan even though it’s been globally rejected and has led to China’s own massive pollution problem. Some global brands, like Ikea, for example, have refused to do business internationally with companies that use coal energy.

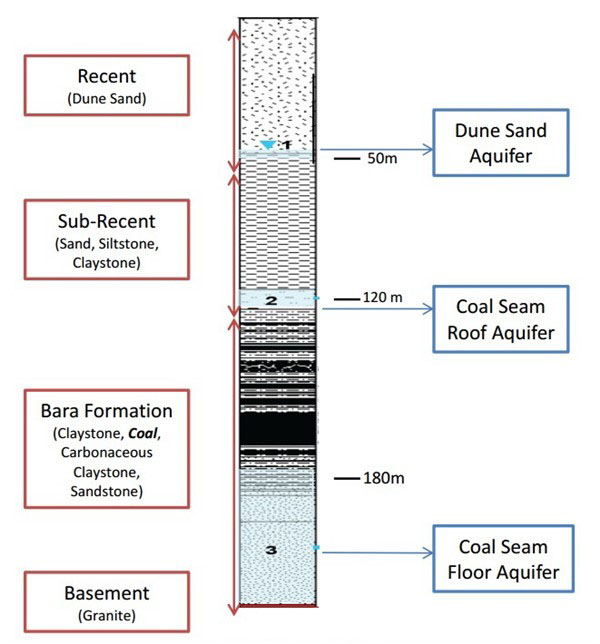

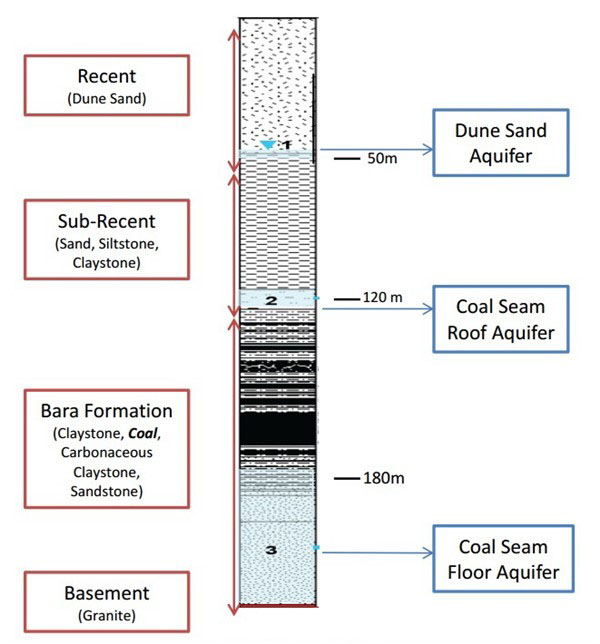

SECMC is going to have to use open pit mining because the coal is buried inside layers of water or aquifers (see image). That water needs to be drained, which is why the company plans to build an effluent disposal reservoir in an area near Gorano, which is about 29km from Islamkot. But now the people who live around here have joined together to protest.

First, the locals dispute the choice of the site at Gorano. Twelve of them filed a petition at the Hyderabad high court on June 30. They took the plea that the mining company had acquired the land under an urgency clause specified in Sections 4, 6 and 17 of the Land Acquisition Act of 1894. This part of the law says that the mining authority can acquire land but only after seeking permission of the land owner. The petitioners say that their permission was not granted and they were not granting permission either. On Dec 6, the judges tasked a committee with looking into the project in two months. The next hearing is on January 19.

The villagers also say that the plan for the reservoir never included an assessment of the socio-environmental impact. They fear that the water will be toxic and will ruin their environment. “Even though it is a desert the selected site is not barren land,” says Leela Ram Advocate, a resident of Gorano who is leading the protest. “It transforms into lush greenery when it rains. There are pasture lands at the site, which provide fodder to livestock, the only source for the residents of the desert.” The area has forest cover as well, which the villagers fear will be affected if the groundwater is interfered with. They also say that if this toxic water is extracted and dumped elsewhere it will ruin any place it is kept. Civil society activists concur. “The reservoir is not feasible environmentally,” says Ali Akbar Rahimoon, a member of the Thar Voice Forum.

A hydrological survey would be needed to work through these issues. But journalist Sohail Sangi, who has worked on issues in Tharparkar, says that none has been done on how they will dispose of the water. He also wants to know if the underground water is public property or the company’s.

According to SECMC’s figures, a total of 30 to 35 cusecs of effluent would be disposed off in to the reservoir for two and a half years and the ‘mine’ water would not be toxic or hazardous. “The water is not at all poisonous,” said a statement from SECMC’s CEO. “It is only groundwater without any industrial effluent [and] is brackish in nature. Brackish water will not be stored in the reservoir permanently, but temporarily for three to four years.”

Locals are also worried seepage from the reservoir will affect their underground water by turning sweetwater wells salty. Water is such a precious commodity for the drought-hit Tharparkar that people lock their tanks to protect their supplies. In the absence of piped water, wells are the only source of drinking water. The people’s fears are based on information that surfaced in assessments that said that the Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) level of this underground water would be around 5000ppm, much higher than the WHO standard that sets the maximum contaminant level for TDS at 1,000 ppm. TDS is directly related to the purity of water, the quality of water purification systems and it is used to determine how safe water is for consumption by humans, animals or for farming.

Coal was first discovered in Thar by chance in 1991 while drilling for water. By 1994, American mining company Johnt Boyd confirmed there were about 175 billion tons of coal. The Sindh government divided it into 13 blocks each with 2b tons of coal reserves. From 2003 to 2008, several foreign firms were involved in feasibility studies, exploration and plans to set up open-pit mines. They included lignite mining and power generation company RWE Germany, China’s Shenhua coal and mineral mining company, Hong Kong-based businessman Gordon Wu. In 2008, the Sindh government opened International competitive bidding for block 2. Engro was selected as a joint venture partner leading to the formation of the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Co Ltd (SECMC) in 2009. Source: Business Recorder

“Seepage would affect wells coming inside the covered area of the reservoir and outside,” argues Rahimoon. “For instance, nine water wells fall within the construction site and 26 are in nearby areas.” Leela Ram added that they did not agree with the company’s statement. “Seepage is definite as Thar’s sand dunes are not capable of bearing the seepage no matter how much pitching is done,” he said. Pitching refers to building up embankments with stone.

And what if the wastewater is dumped near their homes? An estimated 15,000 people live in the surrounding areas. The company has said, however, that the residents will not need to leave because of the reservoir. But at the same time it promises to settle any locals if the need arises. “Not a single family will be migrated or relocated due to the construction of the Gorano reservoir,” said the CEO’s statement. “But in any case, if someone is forced to migrate, the company will make all the necessary arrangements for their relocation and continuation of their livelihood.”

For women like Sita, this rings alarm bells. “The displacement would mean losing the land we have lived on for centuries,” she said. “We would also lose our ancestral chaunra, (a cone-shaped homes made of straw and wood).” Usman Hajjam, a 70-year-old dweller of another affected settlement Suleman Hajjam village thinks that the displacement would mean loss of livestock which is their major source of livelihood.

The villagers are also asking about the actual size of the reservoir. According to SECMC, the reservoir is being built on 1,500 acres out of which 532 acres are private property and the rest is communal grazing land. The Thar Land Grant Policy 1930 permits people to use this land. “Initially SECMC claimed that the reservoir would be constructed on 2,700 acres but now it is saying that the covered area of the reservoir will be 1,500 acres,” Rahimoon added.

For whatever it is worth, Sindh Chief Minister Syed Murad Ali Shah has reiterated the government’s stance that they cannot change the site because there was no other choice when it came to dealing with the water. He called the migration and displacement of people from the area affected by the development “a natural phenomenon”, Dawn reported.

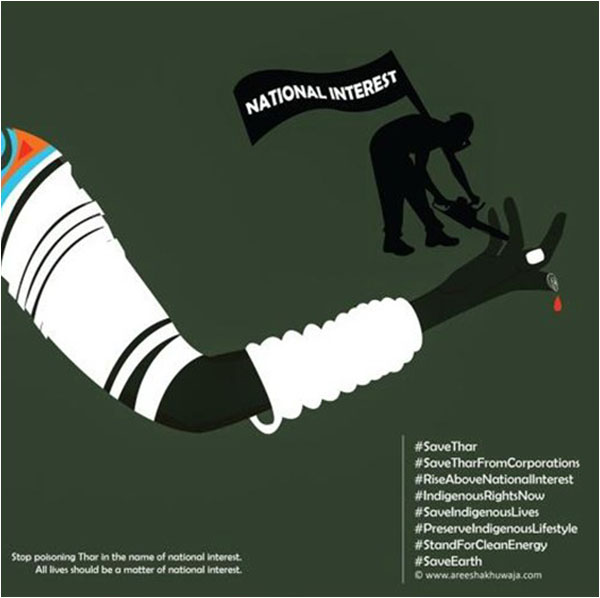

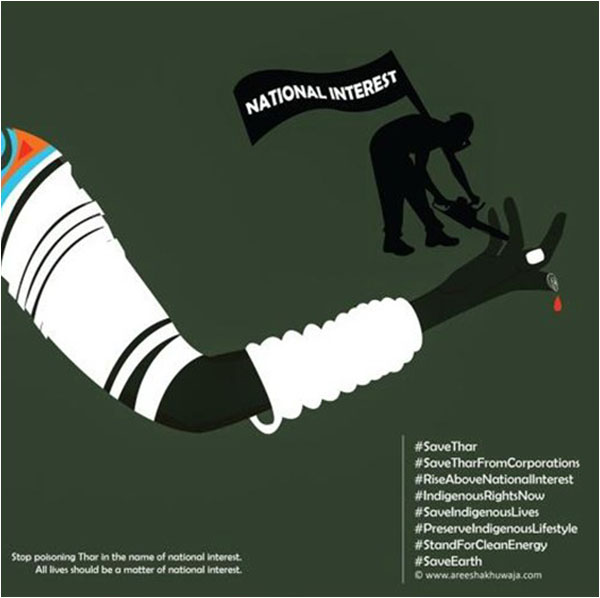

The company has engaged at some level with the locals. For instance, Shamsuddin A. Shaikh, the chief executive officer of the coal mining company, admitted to them making some mistakes. “We might have made some minor mistakes before carrying out the construction work of the reservoir, but we cannot change it now,” Shaikh stated while requesting protesters to end their protest “in the national interest.” A newly appointed spokesperson, Mohsin Babar, told The Friday Times that the protestors had been “misguided” by other people. “Some of them are even parting ways with the protest,” he claimed. He did not, however, mention any more details.

The villagers are also worried that the reservoir would lead to a loss of plant life. A total of 137 plant species have been reported from the Tharparkar area, says Hagler Bailly Pakistan that conducted an environmental and social impact assessment of Thar Coal Block II. These include trees that are a source of income in their lives. The trees are helpful during the drought conditions when rains are scattered and the ground water levels are down. During that time, the livestock becomes highly dependent on trees. “One of the most serious environmental issues is that, at present the felling of the Rohiro tree is banned under the Article 144,” said Rahimoon. “Also, according to the UNDP and Environment Ministry, the gugrall (Camiphera mukul), phoge (Clligonum polygonoides), rohiro (Tecoma undulata), Peeloo (Salvadora persica), Kandi (Prosopis cineraria) and Kombhat (Acacia Senegal) are threatened species.”

The protestors wanted to clarify that they are not opposing the project as such. They are just concerned with the location and their villages. “We proposed four alternate sites which are 5km away from the Rann of Kutch, the Ramsar Site,” says Leela Ram. Protestors say that trying to build the reservoir at Gorano is a bad choice as the village is surrounded by dunes on three sides. The ideal site, they said, is more towards the salt marshes 15km south from Gorano. And indeed, this seems to have been considered an option at one point as a possibly older Engropowergen document on the project says: “Effluent / Groundwater from Thar Block-II Projects will be disposed in the Salt Lakes in or near the Rann of Kutch Area.” CEO Shamsuddin Shaikh told The Friday Times, however, that when they compared Gorano with eight other sites based on a certain criterion, this one was “selected purely on engineering and scientific grounds after meeting all legal and administrative prerequisites.”

As with such development projects that pit nature against ‘progress’, sides have been taken. Few dispute that Pakistan is short on energy and the government has to tackle the energy crisis. Thar’s coal has long been seen as a solution. In the Gorano reservoir case, the villagers await the court’s outcome on the petition and press forward with their protest. Wellwishers have come forward. Renowned Sindhi singer Saif Samejo visited them and even composed a song for their cause: “Bhora Manrhoon” (The simple people). “My song is dedicated to the people of Gorano,” he told The Friday Times. The lyrics are emotional: We are naïve, we are innocent. We are coy, we are trusting… We never intervene in each other’s affairs. Now there will be no turns for water…”

Zulfiqar Kunbhar is a Karachi-based journalist. He tweets at @ZulfiqarKunbhar

Sita Bai, in her 30s, is one of those women, who is protesting with people from 12 villages around Gorano outside the press club. It is her 70th night there—a record not just for the length of the protest but also because the women have left their homes to do it. “It will inundate our entire area, which has been suffering a drought for many years,” she says, referring to their fears of the effect a reservoir will have on their ancestral village.

Sindh’s Thar desert, that lies along the Indian border, has reserves of around 175 billion tonnes of lignite coal. They have been divided into 12 blocks and the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC), a joint venture with the Sindh government, has started excavating in block 2. SECMC plans to excavate two billion tonnes of coal and build a 660 megawatt power plant, which is expected to send power to the national grid by June 2019. This is part of a bigger initiative as Thar’s coal excavation has been included in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Chinese are helping mine the reserves. The criticism has been that China is exporting its coal technology to Pakistan even though it’s been globally rejected and has led to China’s own massive pollution problem. Some global brands, like Ikea, for example, have refused to do business internationally with companies that use coal energy.

SECMC is going to have to use open pit mining because the coal is buried inside layers of water or aquifers (see image). That water needs to be drained, which is why the company plans to build an effluent disposal reservoir in an area near Gorano, which is about 29km from Islamkot. But now the people who live around here have joined together to protest.

This is part of a bigger initiative as Thar's coal excavation has been included in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Chinese are helping mine the reserves. The criticism has been that China is exporting its coal technology to Pakistan even though it's been globally rejected and has led to China's own massive pollution problem. Some global brands, like Ikea, for example, have refused to do business internationally with companies that use coal energy

First, the locals dispute the choice of the site at Gorano. Twelve of them filed a petition at the Hyderabad high court on June 30. They took the plea that the mining company had acquired the land under an urgency clause specified in Sections 4, 6 and 17 of the Land Acquisition Act of 1894. This part of the law says that the mining authority can acquire land but only after seeking permission of the land owner. The petitioners say that their permission was not granted and they were not granting permission either. On Dec 6, the judges tasked a committee with looking into the project in two months. The next hearing is on January 19.

The villagers also say that the plan for the reservoir never included an assessment of the socio-environmental impact. They fear that the water will be toxic and will ruin their environment. “Even though it is a desert the selected site is not barren land,” says Leela Ram Advocate, a resident of Gorano who is leading the protest. “It transforms into lush greenery when it rains. There are pasture lands at the site, which provide fodder to livestock, the only source for the residents of the desert.” The area has forest cover as well, which the villagers fear will be affected if the groundwater is interfered with. They also say that if this toxic water is extracted and dumped elsewhere it will ruin any place it is kept. Civil society activists concur. “The reservoir is not feasible environmentally,” says Ali Akbar Rahimoon, a member of the Thar Voice Forum.

A hydrological survey would be needed to work through these issues. But journalist Sohail Sangi, who has worked on issues in Tharparkar, says that none has been done on how they will dispose of the water. He also wants to know if the underground water is public property or the company’s.

According to SECMC’s figures, a total of 30 to 35 cusecs of effluent would be disposed off in to the reservoir for two and a half years and the ‘mine’ water would not be toxic or hazardous. “The water is not at all poisonous,” said a statement from SECMC’s CEO. “It is only groundwater without any industrial effluent [and] is brackish in nature. Brackish water will not be stored in the reservoir permanently, but temporarily for three to four years.”

Locals are also worried seepage from the reservoir will affect their underground water by turning sweetwater wells salty. Water is such a precious commodity for the drought-hit Tharparkar that people lock their tanks to protect their supplies. In the absence of piped water, wells are the only source of drinking water. The people’s fears are based on information that surfaced in assessments that said that the Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) level of this underground water would be around 5000ppm, much higher than the WHO standard that sets the maximum contaminant level for TDS at 1,000 ppm. TDS is directly related to the purity of water, the quality of water purification systems and it is used to determine how safe water is for consumption by humans, animals or for farming.

The story of Thar’s coal

Coal was first discovered in Thar by chance in 1991 while drilling for water. By 1994, American mining company Johnt Boyd confirmed there were about 175 billion tons of coal. The Sindh government divided it into 13 blocks each with 2b tons of coal reserves. From 2003 to 2008, several foreign firms were involved in feasibility studies, exploration and plans to set up open-pit mines. They included lignite mining and power generation company RWE Germany, China’s Shenhua coal and mineral mining company, Hong Kong-based businessman Gordon Wu. In 2008, the Sindh government opened International competitive bidding for block 2. Engro was selected as a joint venture partner leading to the formation of the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Co Ltd (SECMC) in 2009. Source: Business Recorder

“Seepage would affect wells coming inside the covered area of the reservoir and outside,” argues Rahimoon. “For instance, nine water wells fall within the construction site and 26 are in nearby areas.” Leela Ram added that they did not agree with the company’s statement. “Seepage is definite as Thar’s sand dunes are not capable of bearing the seepage no matter how much pitching is done,” he said. Pitching refers to building up embankments with stone.

And what if the wastewater is dumped near their homes? An estimated 15,000 people live in the surrounding areas. The company has said, however, that the residents will not need to leave because of the reservoir. But at the same time it promises to settle any locals if the need arises. “Not a single family will be migrated or relocated due to the construction of the Gorano reservoir,” said the CEO’s statement. “But in any case, if someone is forced to migrate, the company will make all the necessary arrangements for their relocation and continuation of their livelihood.”

For women like Sita, this rings alarm bells. “The displacement would mean losing the land we have lived on for centuries,” she said. “We would also lose our ancestral chaunra, (a cone-shaped homes made of straw and wood).” Usman Hajjam, a 70-year-old dweller of another affected settlement Suleman Hajjam village thinks that the displacement would mean loss of livestock which is their major source of livelihood.

The villagers are also asking about the actual size of the reservoir. According to SECMC, the reservoir is being built on 1,500 acres out of which 532 acres are private property and the rest is communal grazing land. The Thar Land Grant Policy 1930 permits people to use this land. “Initially SECMC claimed that the reservoir would be constructed on 2,700 acres but now it is saying that the covered area of the reservoir will be 1,500 acres,” Rahimoon added.

For whatever it is worth, Sindh Chief Minister Syed Murad Ali Shah has reiterated the government’s stance that they cannot change the site because there was no other choice when it came to dealing with the water. He called the migration and displacement of people from the area affected by the development “a natural phenomenon”, Dawn reported.

The company has engaged at some level with the locals. For instance, Shamsuddin A. Shaikh, the chief executive officer of the coal mining company, admitted to them making some mistakes. “We might have made some minor mistakes before carrying out the construction work of the reservoir, but we cannot change it now,” Shaikh stated while requesting protesters to end their protest “in the national interest.” A newly appointed spokesperson, Mohsin Babar, told The Friday Times that the protestors had been “misguided” by other people. “Some of them are even parting ways with the protest,” he claimed. He did not, however, mention any more details.

The villagers are also worried that the reservoir would lead to a loss of plant life. A total of 137 plant species have been reported from the Tharparkar area, says Hagler Bailly Pakistan that conducted an environmental and social impact assessment of Thar Coal Block II. These include trees that are a source of income in their lives. The trees are helpful during the drought conditions when rains are scattered and the ground water levels are down. During that time, the livestock becomes highly dependent on trees. “One of the most serious environmental issues is that, at present the felling of the Rohiro tree is banned under the Article 144,” said Rahimoon. “Also, according to the UNDP and Environment Ministry, the gugrall (Camiphera mukul), phoge (Clligonum polygonoides), rohiro (Tecoma undulata), Peeloo (Salvadora persica), Kandi (Prosopis cineraria) and Kombhat (Acacia Senegal) are threatened species.”

The protestors wanted to clarify that they are not opposing the project as such. They are just concerned with the location and their villages. “We proposed four alternate sites which are 5km away from the Rann of Kutch, the Ramsar Site,” says Leela Ram. Protestors say that trying to build the reservoir at Gorano is a bad choice as the village is surrounded by dunes on three sides. The ideal site, they said, is more towards the salt marshes 15km south from Gorano. And indeed, this seems to have been considered an option at one point as a possibly older Engropowergen document on the project says: “Effluent / Groundwater from Thar Block-II Projects will be disposed in the Salt Lakes in or near the Rann of Kutch Area.” CEO Shamsuddin Shaikh told The Friday Times, however, that when they compared Gorano with eight other sites based on a certain criterion, this one was “selected purely on engineering and scientific grounds after meeting all legal and administrative prerequisites.”

As with such development projects that pit nature against ‘progress’, sides have been taken. Few dispute that Pakistan is short on energy and the government has to tackle the energy crisis. Thar’s coal has long been seen as a solution. In the Gorano reservoir case, the villagers await the court’s outcome on the petition and press forward with their protest. Wellwishers have come forward. Renowned Sindhi singer Saif Samejo visited them and even composed a song for their cause: “Bhora Manrhoon” (The simple people). “My song is dedicated to the people of Gorano,” he told The Friday Times. The lyrics are emotional: We are naïve, we are innocent. We are coy, we are trusting… We never intervene in each other’s affairs. Now there will be no turns for water…”

Zulfiqar Kunbhar is a Karachi-based journalist. He tweets at @ZulfiqarKunbhar