In September 2016, I was doing a story on the military's media policy and in the process, I interviewed a number of security experts, retired and serving military officials - both foreign and Pakistan - and media professionals. One common theme particularly attracted my attention: all of them expressed a similar opinion on the need and requirement for the military to run an independent and concerted media campaign in a fractured society like Pakistan, especially when the military was engaged in two counter-insurgency operations inside the country.

By that year, the military was claiming to have broken the back of the militancy in the erstwhile tribal areas after a decade long campaign in the Pak-Afghan border areas. In those days, ISPR press releases made headlines in most prominent news channels and newspapers, and leading magazines were carrying cover stories on the military's gallantry in the tribal areas.

I remember interviewing Brian Cloughley, a renowned author and historian of the Pakistan Army. He served in Pakistan for eight years, first as a Deputy Chief of the UN Military Observer Group for Kashmir and then as Australian Defense Attaché in Islamabad. In the interview conducted through email, he defended the Pakistan Army’s right to project its own narrative in Pakistan, especially when it was engaged in a counter insurgency operation within the borders of the country. I diligently reported on all of this.

I was developing doubts about the Army's right to run independent media campaigns, particularly after noticing the latitude provided by successive civilian governments to the Army and its leadership to project a very subjective institutional truth to the people of Pakistan, specifically on its counter-insurgency role in the country. My doubt grew in intensity after successive military leaders in the post-Musharraf period expanded this narrowly defined latitude to include purely political themes.

In later years, the ISPR appeared to be working as a political arm and propaganda mouthpiece of the military leadership. It started behaving as if it were not the media wing of a professional army, but rather it acted as the media wing of a political entity, which sought to project its political positions on every issue, ranging from the opposition leader’s meeting with the Chief of the Army Staff, clarifying the Army’s position on a public assertion of a visit from the Iranian President, praising the budget proposals of an elected government, opposing political and intellectual trends and condemning their representatives in the media, labelling journalists as enemies of the state, and taking positions on political issues and political favorites as a matter of routine.

The massive scale of the military’s propaganda machinery drowned out the voices which objected to the growing political role of the ISPR and its successive chiefs. Their role in domestic politics was matched by the increased flow of ISPR’s press releases and the Army Chief’s public assertions, which directly dealt with foreign policy matters. In fact, on a number of occasions in the post-Musharraf period, Army chiefs, especially General Qamar Javed Bajwa, made routine policy statements on foreign policy. For instance, in April 2018, General Bajwa offered peace talks to India, something which was extremely unusual for an Army chief to do. ISPR duly reported these policy statements through its press releases.

By 2018, the ISPR was clearly overstepping its traditional role as a mouthpiece to project the Army’s side of the story related to counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations in the North West and South West of the country. It was playing a political role - out and out.

As a consequence of the ISPR claiming this increased space in the nation’s media discourse, cryptically threatening political opponents in crowded press conferences have become the new normal for ISPR chiefs. Similarly, the ISPR has favorites in the political arena and media industry. They were dead set in their opposition against some independent journalists and had no qualms in mentioning their names in press conferences. While it is true that the ISPR has always named a few journalists as occupying their target lists in the past, they have never dared to mention their names in public. This changed in the post-Musharraf period. Journalists were openly bashed.

Unsurprisingly, these developments were a by-product of a much larger encroachment on the political and executive authority of the prime minister and federal government by successive Army Chiefs in the post-Musharraf period. In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to suggest that the office of Army Chief emerged as a parallel executive authority in the country in this period. He acted as diplomat-in-chief; he also acted as a mediator between the opposition which remained in agitation mode throughout this period, and successive governments, which appeared to be dependent on the immense capacity of the military to orchestrate change in the political arena.

So, it was not at all surprising when the DG ISPR came up with a political statement after the then opposition leader met the then Army Chief in a late-night meeting to control the ongoing agitation. The DG ISPR even managed to gather the courage to reject a notification of the Federal Government outright through a tweet. The then government had no capacity to express its anger over this behavior. It was only further cornered in the political arena. In fact, one of the officers of the ISPR who served as DG ISPR in those days became a star and he still projects himself as a star, despite the fact he now serves in the regular army and is believed to be prohibited from interacting with the media without official authorization.

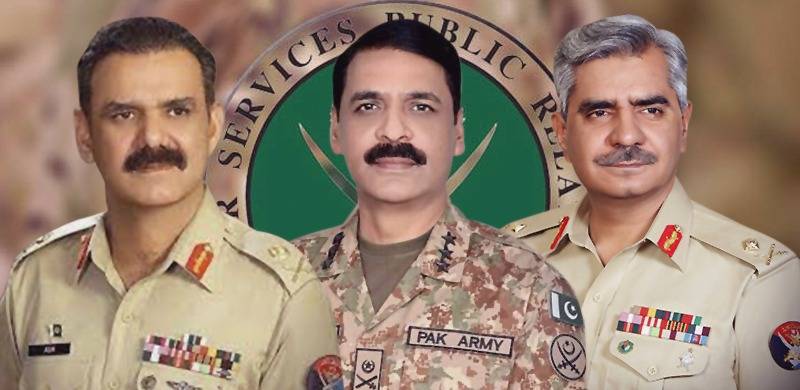

The culmination of all this behavior was the press conference that the then DG ISPR, Major General Babar Iftikhar and DG ISI, Lt. General Nadeem Anjum addressed to criticize the PTI chairman, Imran Khan, something which should be described as an outright political act. The basic problem with this behavior is that the military’s leaders have no qualms about projecting their institutional logic on a national scale and sincerely expect that its precepts will be acceptable to all and sundry.

An independent media policy should be the exclusive domain of political governments, which are supposed to set strategic political directions for every institution under the executive authority of the state. The Pakistani media and a number of political groups however, especially those in the opposition, are not ready to assign the military a role subservient to political governments.

Such a situation is ripe for further exploitation when the military has an outlet - in the shape of the ISPR - which has direct access to the public and has developed a tradition of adopting bold political positions - that is then utilized by troublemakers in the media and political groups to undermine democratically elected governments. In the post-Musharraf era, we have seen that ISPR and its managers have become ready partners in the endeavors of political troublemakers seeking to instigate chaos in the political arena.

By that year, the military was claiming to have broken the back of the militancy in the erstwhile tribal areas after a decade long campaign in the Pak-Afghan border areas. In those days, ISPR press releases made headlines in most prominent news channels and newspapers, and leading magazines were carrying cover stories on the military's gallantry in the tribal areas.

I remember interviewing Brian Cloughley, a renowned author and historian of the Pakistan Army. He served in Pakistan for eight years, first as a Deputy Chief of the UN Military Observer Group for Kashmir and then as Australian Defense Attaché in Islamabad. In the interview conducted through email, he defended the Pakistan Army’s right to project its own narrative in Pakistan, especially when it was engaged in a counter insurgency operation within the borders of the country. I diligently reported on all of this.

I was developing doubts about the Army's right to run independent media campaigns, particularly after noticing the latitude provided by successive civilian governments to the Army and its leadership to project a very subjective institutional truth to the people of Pakistan, specifically on its counter-insurgency role in the country. My doubt grew in intensity after successive military leaders in the post-Musharraf period expanded this narrowly defined latitude to include purely political themes.

In later years, the ISPR appeared to be working as a political arm and propaganda mouthpiece of the military leadership. It started behaving as if it were not the media wing of a professional army, but rather it acted as the media wing of a political entity, which sought to project its political positions on every issue, ranging from the opposition leader’s meeting with the Chief of the Army Staff, clarifying the Army’s position on a public assertion of a visit from the Iranian President, praising the budget proposals of an elected government, opposing political and intellectual trends and condemning their representatives in the media, labelling journalists as enemies of the state, and taking positions on political issues and political favorites as a matter of routine.

The massive scale of the military’s propaganda machinery drowned out the voices which objected to the growing political role of the ISPR and its successive chiefs. Their role in domestic politics was matched by the increased flow of ISPR’s press releases and the Army Chief’s public assertions, which directly dealt with foreign policy matters. In fact, on a number of occasions in the post-Musharraf period, Army chiefs, especially General Qamar Javed Bajwa, made routine policy statements on foreign policy. For instance, in April 2018, General Bajwa offered peace talks to India, something which was extremely unusual for an Army chief to do. ISPR duly reported these policy statements through its press releases.

By 2018, the ISPR was clearly overstepping its traditional role as a mouthpiece to project the Army’s side of the story related to counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations in the North West and South West of the country. It was playing a political role - out and out.

As a consequence of the ISPR claiming this increased space in the nation’s media discourse, cryptically threatening political opponents in crowded press conferences have become the new normal for ISPR chiefs. Similarly, the ISPR has favorites in the political arena and media industry. They were dead set in their opposition against some independent journalists and had no qualms in mentioning their names in press conferences. While it is true that the ISPR has always named a few journalists as occupying their target lists in the past, they have never dared to mention their names in public. This changed in the post-Musharraf period. Journalists were openly bashed.

Unsurprisingly, these developments were a by-product of a much larger encroachment on the political and executive authority of the prime minister and federal government by successive Army Chiefs in the post-Musharraf period. In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to suggest that the office of Army Chief emerged as a parallel executive authority in the country in this period. He acted as diplomat-in-chief; he also acted as a mediator between the opposition which remained in agitation mode throughout this period, and successive governments, which appeared to be dependent on the immense capacity of the military to orchestrate change in the political arena.

So, it was not at all surprising when the DG ISPR came up with a political statement after the then opposition leader met the then Army Chief in a late-night meeting to control the ongoing agitation. The DG ISPR even managed to gather the courage to reject a notification of the Federal Government outright through a tweet. The then government had no capacity to express its anger over this behavior. It was only further cornered in the political arena. In fact, one of the officers of the ISPR who served as DG ISPR in those days became a star and he still projects himself as a star, despite the fact he now serves in the regular army and is believed to be prohibited from interacting with the media without official authorization.

The culmination of all this behavior was the press conference that the then DG ISPR, Major General Babar Iftikhar and DG ISI, Lt. General Nadeem Anjum addressed to criticize the PTI chairman, Imran Khan, something which should be described as an outright political act. The basic problem with this behavior is that the military’s leaders have no qualms about projecting their institutional logic on a national scale and sincerely expect that its precepts will be acceptable to all and sundry.

An independent media policy should be the exclusive domain of political governments, which are supposed to set strategic political directions for every institution under the executive authority of the state. The Pakistani media and a number of political groups however, especially those in the opposition, are not ready to assign the military a role subservient to political governments.

Such a situation is ripe for further exploitation when the military has an outlet - in the shape of the ISPR - which has direct access to the public and has developed a tradition of adopting bold political positions - that is then utilized by troublemakers in the media and political groups to undermine democratically elected governments. In the post-Musharraf era, we have seen that ISPR and its managers have become ready partners in the endeavors of political troublemakers seeking to instigate chaos in the political arena.