Editorial Note: This article is being published for its insights into Baloch history, society and custom. It is emphasised that the author is not advocating trial by fire, but studying a custom, which may not necessarily be practised at the present time.

***

Pakistani society contains rich and diverse customs, but it is usually depicted as a monolithic Islamic society. Instead of pretending that diversity does not exist or looking down on difference, Pakistanis should value it as part of their common historical and cultural legacy. As an anthropologist, I have studied local customs in different societies of Africa, Asia, Europe and the USA.

I was fortunate to be able to see and record pre-Islamic customs in tribal societies in Pakistan. In this article, I will focus on one such custom from Balochistan which I found intriguing: it was an ordeal that we might call trial by fire. This was once a custom in the Bugti Agency in Balochistan. I emphasise the past tense because it was recorded several decades ago. In any case, the Bugti Agency, it must be noted, as a tribal Agency, was not subject to the normal criminal and civil procedure codes of Pakistan and was therefore administered by elders according to custom and riwaj.

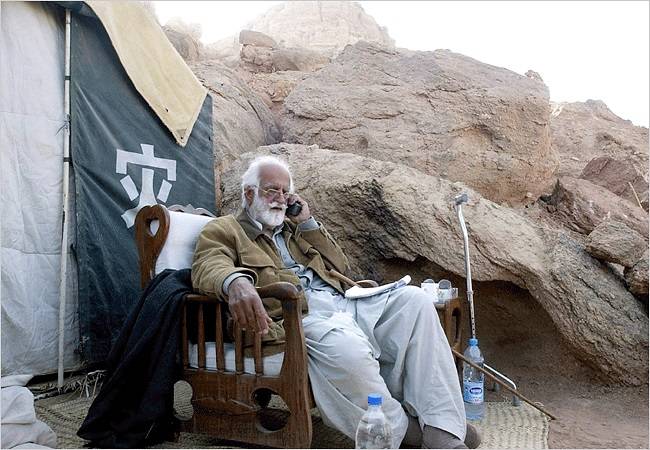

I came across the practice of trial by fire among the Bugti when I was Commissioner, Sibi Division, in the late 1980s. I sought to understand better the people in my charge. As a trained anthropologist, I was fascinated. As head of Sibi Division, I was also in charge of the Bugti Agency and came to know and regard the tribe and its chief Nawab Akbar Bugti. My bodyguard was also Bugti, and it gave me a chance on our long journeys to talk to them. Besides, I had the extraordinary privilege of having long sessions with Nawab Akbar Bugti, discussing tribal societies and its politics. He had read and understood the theories of Ibn Khaldun and I was amazed at his knowledge and intelligence. I often asked myself: how many Pakistani politicians would have read Ibn Khaldun, which the Nawab had done in Sahiwal jail, and then attempt to apply Khaldunian ideas to his own Bugti tribe?

When I took over as Commissioner in Sibi, my staff and I were surprised to learn that the Nawab wanted to talk to me on the phone. We wondered what crisis had prompted his call. In fact, he wanted to talk about my book Pukhtun Economy and Society (1980), which is my doctoral thesis and a study of the Mohmand tribe in what is now the KP province. He made some sharp observations while comparing Pakhtun and Baloch tribes. I was impressed. No one, not even my civil service colleagues, had mentioned my book.

As a result of our interactions, the Nawab developed an affection and respect for me. His attitude to me was soon known in the land and assisted my administration in performing its duties. Previous administrators, seeing the Nawab as hostile and finding him uncooperative and even offensive, tended to keep their distance from him.

I thus had extraordinary access to the Bugti. Wishing to preserve information about Balochistan, especially about something as rare as the fire ritual, I wrote up a case study which is still introductory in nature, “Trial by Ordeal Among Bugtis: Ritual as a Diacritical Factor In Baloch Ethnicity,” (as a chapter In Marginality and Modernity: Ethnicity and Change in Post-Colonial Balochistan, edited by Paul Titus, Oxford University Press, 1996. pp. 51-77).

Information for this article was gathered when I lived among the Bugti over three decades ago. Society and its rituals and values have since moved on. Most significantly, Nawab Akbar Bugti,whose towering presence played an important role in upholding Bugti identity, is no longer alive. On hearing of the Nawab’s violent death in 2006, I was on a personal level profoundly dismayed – especially at its brutal and cruel manner.

The thesis

The central question of boundary maintenance and ethnic identity among the Baloch was raised tentatively by Fredrik Barth in Ethnic Groups and Boundaries (1969); but it was not explored substantially or extensively by anthropologists. Perhaps the remote and hostile environment of Balochistan is the explanation, perhaps the difficulty of obtaining government permission to travel in the area, perhaps the attraction of studying the better documented and romanticised Pashtun (or Pathans) to the north. For the Baloch, it is generally accepted that language and genealogy are the two most-commonly recognised diacritica of ethnicity. But through the process of cultural osmosis with other non-Baloch groups, these factors often tend to become blurred. Ritual, then, I will argue, assumes importance in the definition of Baloch ethnic identity and boundary maintenance.

We can view Islam as an orthodox universal religious system adjusted to tribal custom; it is the phenomenon of the Great Tradition encompassing the Little Tradition

The ritual I will discuss is practiced by the Bugti, a major Baloch tribe. It is the “trial by ordeal” – the use of fire to judge serious offences. For a Bugti to accept the validity and legitimacy of this ritual is to underline faith in Bugti riwaj, custom and tradition, in “Bugtiness”, in the purity of an ideal past. But there remains the important question of Islam, the religion of the tribe.

We can view Islam as an orthodox universal religious system adjusted to tribal custom; it is the phenomenon of the Great Tradition encompassing the Little Tradition (Akbar Ahmed, Discovering Islam: Making Sense of Muslim History and Society, 2002). The ‘Islamisation’ of a pre-Islamic custom highlights two apparently contradictory movements among the Bugti: the desire to emphasise an Islamic identity while preserving a pre-Islamic one. Through an examination of the fire ritual, we are thus able to explore how Muslim tribesmen ‘Islamicise’ a non-Islamic custom. We will witness the process of the Islamisation of tribal customs through the application of an Islamic veneer and a sprinkling of Quranic references. The fusion of Islamic law and Bugti custom remove ambiguity from the tribesman’s mind and reinforces cohesiveness in changing times. However, there is also structural connection with the political arrangements of the tribe which underpin the fire ritual and provide it vitality. It is in the form of the strong, central authority embodied in the tribal chief (in our case, Nawab Akbar Bugti). Representing custom and tradition, the chief supports the ritual as demonstrative of Bugti identity. Put simply, to oppose the ritual is to negate Bugtiness; to support the chief is to uphold it. But Islamic scholars criticised the ritual as un-Islamic. Certain dilemmas thus remained unresolved for the Bugti. Tentative probes and exploratory ideas are thus presented.

Although ecstatic forms of worship or trance-like expressions of religious zeal among tribal peoples are well-documented in the literature, here we shall not discuss notions of redemption and salvation or scoring points with God by inflicting pain on the self. We will discuss a cold-blooded alternative to the legal and judicial system of Pakistan, one accepted by the participants in a rational frame of mind and conducted with the senses intact.

Ibn Khaldun and Nawab Akbar on tribes

In order to explain the significance of the fire ritual in an Islamic segmentary tribal society, I shall go beyond Durkheim, Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard and their discussions of witchcraft, oracles and shamans – and refer, instead, to Ibn Khaldun. I shall argue that for the Bugti, the ritual is the provenance not of witch doctors but of the segmentary tribe.

Ibn Khaldun and Nawab Akbar posed the same central question concerning the social organisation and identity of tribal society. Both of them, one a social philosopher of tribal Islam, and the other the head of an Islamic tribe, came to the same conclusion: the latter because of his affection for tribal society the former in spite of his aversion to it. The question, of course, is: what factors maintain ‘cohesion’ or integrity in tribal society? Ibn Khaldun's answer, asabiyah, or ‘group feeling,’ is nothing more than the Nawab’s ‘tribal’ or ‘Bugti identity.’

Both lbn Khaldun and the Nawab argued that to maintain cohesion, tribesmen must stay home. By not wandering off from their remote hills in search of adventure and conquest, the tribesman is not exposed to the corrupting and, more important, disintegrating influences of the settled life of the plains and their cities. By foregoing conquest and staying at home, he preserves his tribal customs, integrity and identity. As we know, Ibn Khaldun’s Berbers did not stay in their mountains. By conquering less martial plains and people with little social cohesion, they settled among them and, within the short space of three to four generations, became like them. The Bugtis, on the other hand, the Nawab pointed out, remained home, and thereby maintained their identity. The preservation of Bugti customs, like trial by ordeal, thus took on ideological significance in the argument. If we strip away the layer of symbolism, reducing the ritual to a formula, fire = Nawab = tribe, we are in a better position to understand the phenomenon. Both those Bugtis who supported the Nawab and those who opposed him are inclined to interpret the ritual in the light of the formula. The Bugtis thus interpreted the fire ritual not only through social processes but also historical ones, not only through tribal philosophy but also cosmic ideology.

The Bugtis

The Bugtis are organised along the lines of segmentary tribal society familiar in the literature (see for examples, African Political Systems, Fortes and Evans-Pritchard 1970; and Tribes without Rulers-Studies in African Segmentary Systems, Middleton and Tait 1970). They claim descent from Rind, son of Mir Jalal Khan, the chief of the Baloch, who ruled over 44 bolak, or tribes, in the Persian province of Sistan. The Bugtis, one of these tribes, were settled on the banks of the river Bug—hence the name Bugti. Mir Ali, son of Rind, along with his close kinsman Mir Chakar, took part in the great Baloch migration from Sistan to Makran and eventually settled in what is now the Sibi division of Balochistan. Sibi became the headquarters of Mir Chakar, who is widely considered the greatest Baloch chieftain in history.

In order to explain the significance of the fire ritual in an Islamic segmentary tribal society, I shall go beyond Durkheim, Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard and their discussions of witchcraft, oracles and shamans – and refer, instead, to Ibn Khaldun

The Bugti tribe is composed of seven major clans, which are further subdivided into increasingly small units, all related on the genealogical chart. Sardars and waderas (petty chiefs) head the clans and sections. The Rahejav is the dominant clan. The Bivraghzai, the ruling family of the Bugti, who claim direct descent from Mir Ali, belong to the Rahejav. The remaining six clans, Masori, Kalpar, Mondrani, Shambani, Nothani, and Pirozani are, in the classic segmentary tribal tradition, named after eponymous ancestors. Also in the same tradition, they occupy demarcated and recognised territorial areas corresponding to their clan.

The Maratha clan of the Bugti is not descended from the Bugti ancestor but affiliated to the tribe. lt claims descent from the Hindu Marathas captured by the Bugtis when they raided India with Ahmad Shah Durrani in the eighteenth century. In time they underwent ‘Bugtiisation’ and became Muslims. Although for all practical purposes they may now be considered Bugtis, and are even in the forefront in education and employment, they were once considered little better than bonded labour. They could not own or buy land. Up to two generations ago they could be “bought” for twenty or thirty rupees. Their women were fair game for Bugtis (See Sylvia Matheson’s, The Tigers of Balochistan, 1980).

The process of ‘Bugtiisation’ has also spread to certain Hindu groups living in the Agency. For instance, Arjun Das, a Hindu living in Dera Bugti, was allowed to call himself Arjun Das Bugti by the Nawab. Because Arjun Das Bugti was a member of the Provincial Assembly of Balochistan, this example of Bugtiisation was more than just a symbolic local gesture.

In 1901, the Bugti population was estimated to be about 15,000 (Gazetteer, 1980:212); and according to the latest census taken in 2017 it was 313,110. Many Bugtis have drifted southwards seeking employment in the Sindh province. The Dera Bugti Agency was created as an administrative unit in 1983 and covers an area of 9,656 square kilometres. It corresponds to a District, the main unit of administration in Pakistan, but because it is an Agency not all the laws of Pakistan apply in it. Through its name it further reinforces Bugti tribal identity in the country.

For the Baloch “the Bugtis are Baloch of the purest dew” (Muhammad Sardar Baloch, 1984:241). The British, too, singled out the Bugtis as “the bravest of the hill tribes. Physically they are some of the finest men among the Baloch, and intellectually, perhaps, they are the least bigoted.” (Gazetteer, 1980, Vol. 1:218). In their white dress, their locks flowing down to their shoulders, their beards combed in a characteristic style and faces partly hidden by white turbans, their deadly looking daggers and guns proudly displayed as ornaments, they formed a striking picture. “The Tigers of Balochistan,” a smitten Mrs Matheson, one of the few foreigners who lived in the Bugti area, called the Bugti.

The white clothes and long hair of the Bugti were traced by the Nawab to pre-Islamic Persian influences. Zar Oshtar, the golden camel corrupted to Zarathustra, the prophet of the Zoroastrians, fire-worshippers par excellence, wore golden locks. The Zoroastrian priests and chiefs wore white. Persian civilisation, the Nawab postulated, provided the matrix for Baloch culture.

The main ideals of the tribe based in the wider Baloch code of honour were hospitality, bravery, and a romantic chivalry where women were involved. Women were never molested in peacetime or in battle; cases of adultery were considered a breach of honor, and the woman was killed, along with her lover, in what is called sia kari or “black work.” It is the same chivalry which disallowed women—or children—from being tried by ordeal however serious the offence. If the woman was married, her husband, or if she had none, her father or other male kinsman, was put to trial in her place.

Honour, warrior, sword and fire were words with which Bugti tradition was imbued. They formed the themes of ballads and songs and represented the main pillars of Bugti identity. The removal of one of these pillars would mean the collapse of the edifice of heroic tradition. The fire ritual may thus be seen as linked to Bugti identity and honour. The removal of the ritual would mean not only the loss of the institution itself but also an important symbol of Bugti identity.

Certainly, the most dramatic development in the history of the Bugtis came in the 1950s with the discovery of gas, the largest natural gas field in Asia, in the Sui area. Owing to the presence of the Pakistan Petroleum Company a number of developments took place in Bugti society. Bugti children began attending the well-run Company school. About fifty per cent of the 700 boys in the school in my time were Bugti, the rest were from the families of the non-local employees of the company; significantly, some Bugti girls also attended. The Bugti boys appeared clean, bright and competitive; when I visited the school the top student was a Bugti. When the senior class was questioned as to what professions they would want to take up, their answers were indicative of coming trends in Bugti society: doctors and engineers rather than policemen and leaders. The girls, who tended to disappear after the fourth or fifth grade back to the seclusion of their homes, were the first Bugti women to attend school. This was a significant break with the past.

Another development was the economic rise of the once lowly Marathas, who joined the Company as unskilled labourers a generation ago, a time when the Bugtis – whose status came from their tribal standing – disdained such work. The same Marathas were now in positions of authority as supervisors and foremen, with their relative economic wellbeing evident to all. The older, tribally more important Bugtis were left scurrying about for any kind of job with the Company and resented the economic superiority of the Marathas.

Both lbn Khaldun and Akbar Bugti argued that to maintain cohesion, tribesmen must stay home. By not wandering off from their remote hills in search of adventure and conquest, the tribesman is not exposed to the corrupting and, more important, disintegrating influences of the settled life of the plains and their cities

Viewing some of the changes in society, the Nawab lamented the passing of tradition and the fading of custom: “There is no purity left. Honour and custom are being swept away. Old values are going.”

The Nawab’s forceful opinions, delivered from his home in Quetta and in Dera Bugti Agency, and his maverick politics, kept him in the media. He led a political party he himself founded, the Jamhoori Watan Party, and took swipes at anyone who incurred his wrath. At his home in Dera Bugti at a dinner he gave in my honour, he recounted a recurring nightmare: “I was lying in a room like a corpse covered by a white sheet with other people similarly covered. Suddenly I felt some threatening people were coming to castrate me and l woke in a cold sweat. Our politics is like that. I will not let anyone castrate me.”

It is difficult to elicit a neutral opinion on the Nawab from the Bugti. He evokes strong likes or dislikes. To his critics, the Nawab bears comparison not with Ibn Khaldun but with another medieval political philosopher Machiavelli. The voices of opposition could be heard even within his own Rahejav clan. They carried as far as the citadels of power in Islamabad. Among his most notable critics were Ghulam Qadir of Bakar, a wadera of the Masori clan, and Ahmedan, the last chairman of the Agency Council and himself Rahejav. In early 1986, the Nawab knocked off Ahmedan’s turban in public after a heated exchange of words in Dera Bugti. This is a grave insult, and the action was widely discussed. Ghulam Qadir was most vocal. An MA in Urdu, he was a member of the Majlis-i-Shura, the Council of Advisers to the President of Pakistan, and has represented Pakistan at the United Nations: “We are no longer his slaves (ghulam), we live in a free country and are azad (free).” His critics saw no romance or merit in the Nawab and lived in dread of him. “I am number one on his hit list,” ruminated Ghulam Qadir.

The example most commonly cited by the critics of the Nawab of all that is evil and superstitious is the ritual of trial by ordeal. Ghulam Qadir said, “The Nawab uses the fire ordeal to terrorise his tribe. Fire can only burn. Why doesn’t he—or his immediate kin—undergo the trial themselves? They are also accused of serious offences but never face the fire.”

However, to dismiss the Nawab as a petty tyrant, as his critics did, would be an anthropological mistake for the purposes of our discussion. In his person, the Nawab provided a symbol to his tribe, in his philosophy, an identity and in his rebellious stance to authority tribal pride. We will note in the following cases how deeply intertwined the Nawab was with the ritual.

Trial by Ordeal – Case Studies

Among the Bugti, serious offences—murder, rape, kidnapping, theft (20,000 rupees and more)—were tried by the fire ordeal, commonly called asa janti “to put in fire.” Both parties, the accused and the plaintiff, often preferred this method to the lengthy and complicated procedure of the official courts. As we will see from the following case-studies, there appeared to be a rough and ready justice in this method. However, it is also clear that a certain ambiguity regarding the outcome remained.

Although the person conducting the ritual was usually a religious figure, or a neutral man enjoying a good reputation, acceptable to both parties, it was usually presided over by the Nawab, his immediate male kinsman, or the wadera of the area where the trial was conducted. The ritual centred around a ditch seven yards long, two feet deep, and one and a half feet wide. In the last century the accused walked over seven red-hot stones, (Army Intelligence Branch India, 1906, Vol. 1:221). First, dry wood was burnt in the ditch. When the flames were exhausted and only the smouldering red-hot embers remained, seven leaves of the pir or pillo tree were dropped in to test the heat. Then the conducting arbiter walked around the ditch seven times holding the Holy Quran aloft. He chanted seven times to the Holy Quran: “The power of truth rests in you. If this person is guilty, he should burn, if innocent he should not.” Addressing the fire, he mentioned the name of the accused and his alleged crime, and added: “If he is guilty, he should burn, if not, oh fire, be cold in the name of God Almighty and the Holy Quran.” (The invocation to the fire is called drohi, that to the Holy Quran, saak). The accused then walked barefoot, in seven measured steps, through the ditch. After he emerged, his feet were washed and placed for a few minutes in a bowl of fresh goat blood (two goats are ‘sacrificed’ for the ordeal, both paid for by the accused). The feet were then examined carefully for bums. If there were none, the accused was declared innocent of the crime. If the feet exhibited burn marks, he was presumed guilty, the sum of money deposited with the elders (raised to 10,000 rupees by the Nawab) before the ritual by the complainant was then awarded: if innocent, the accused received the deposit; if guilty the money was returned to the complainant, with the accused having to pay the fine.

‘Fire reveals the truth’ vs ‘Fire burns’

I recorded several cases of the ordeal by fire. Those that appeared to establish the truth as supported by the Nawab’s camp were hailed with the cry, “fire reveals the truth.” I also recorded several cases that the opposition to the Nawab pointed out, some recounted by Ghulam Qadir. Here the opposition simply said, “fire burns.”

I recount some cases to give an idea of how they were conducted. In one case two rifles were stolen and two Bugtis were accused in the Pat Feeder area of the Naseerabad District bordering on the Dera Bugti Agency. Both were put to trial by ordeal and were burnt. However, the accused claimed they were innocent and raised an objection on a technical point—the critical oath to the Holy Quran was not administered. The accused insisted that owing to this breach of custom, they were prepared to go through the ordeal again. They appealed to the Nawab. The Nawab appointed an arbiter, and the ordeal was conducted according to custom. This time, the accused emerged without any harm and were declared innocent. They were awarded 5,000 rupees each as compensation.

It is difficult to elicit a neutral opinion on the Nawab from the Bugti tribe. He evokes strong likes or dislikes. To his critics, the Nawab bears comparison not with Ibn Khaldun but with another medieval political philosopher Machiavelli. The voices of opposition could be heard even within his own Rahejav clan. They carried as far as the citadels of power in Islamabad

The following cases were recounted by Ghulam Qadir who was witness to them. Ghulam Qadir spoke of one case in which he was personally involved. His family killed a man. The dead man’s relatives blamed Qadir. They insisted that he should follow riwaj and walk through fire to establish his innocence. Qadir refused, saying “fire burns.” He stated indignantly: “How can I, an educated man who has been to America, be expected to believe in such ignorance and superstition? It is un-Islamic also.” He was in mortal danger because of this, as he had become a target for his enemies by refusing riwaj.

In the winter of 1983, a murder was committed in Bakar. The dead man’s brother accused Palawan, who denied the charge. Palawan was put through the test and his feet were burnt. Palawan had to pay 40,000 rupees to the family of the murdered man. Ghulam Qadir swore on the Holy Quran that he knew who the murderers were and that Palawan was innocent. Indeed, sometime later the actual murderers confessed to the crime, and an agreement was reached between the accused and the family of the deceased.

A Bugti was building a house and put his jewellery in a hole in the wall and left for Sind. On his return he accused the mason, another Bugti, of theft. The mason was ordered to walk through fire and was burnt. He had to pay compensation for the jewellery. Later the owner remembered that he had put the jewellery somewhere else. A jirga declared the mason innocent and ordered the jewellery to be given to him as compensation.

Amir Jan, a casual unskilled labourer in Sui, described his experience of the fire ordeal to me. A few years earlier he was accused of burning crops in the Pat Feeder area. He denied the charge and declared he would undergo trial by ordeal. He did so and went free. When I asked him if he had felt any pain, he said he had not: “I could not, as the Holy Quran was there. If a Muslim does not have faith (itbar) in the Holy Quran, he has no faith.”

Discussion

The Abrahamic tradition tells us many stories of fire that does not burn. One of the most dramatic is of Abraham (or Ibrahim) facing fire and coming out unscathed. Nimrod has Abraham thrown into a burning furnace to test the powers of Abraham’s unseen God. If Nimrod declares Abraham is unharmed then there indeed is a powerful God that can prevent fire from harming people. Abraham, as we know, survived the trial by ordeal.

Similarly, the Ramayana described the trial by fire ordeal of Lord Rama’s wife Sita. The Ramayana established that the trial by ordeal was a universal ritual.

If such customs still survived in the remote areas of a Muslim nation like Pakistan, it is clear they were influenced by Hindu custom. There are other shared features across cultures. The number seven is also prominent in the Bugti fire ritual: the length of the ditch in which the fire is burnt is seven yards or paces, seven leaves are dropped in the fire, the Holy Quran is carried around the fire seven times, the accused walks seven paces through the fire. It is easy to spot the use of the figure seven in various religions and cultures. Agni has seven arms, and seven rays of light pour forth from him. Hindus who are cast into hell for lying will be punished with seven generations of ancestors and seven generations of descendants. Hindus circle seven times round the ritual fire for marriage rites, and in death are shrouded in seven yards of cloth. The Book of Common Prayer refers to “seven-fold gifts” (Ordering of Priests, Veni, Creator Spiritus). “Seven Spirits” are referred to in Saint Matthew (The New Testament Matt. J 2, v. 45). Edward Fitzgerald’s Omar Khayyam laments the passing of Jamshyd’s “sevenringed cup.” Saat seheli, seven friends, is a common Indian figure in popular folk-lore. There are seven wonders of the world and seven days in the week.

Islam, too, appears to accord significance to the number seven. The first Surah of the Holy Quran, Al-Fateha, has seven verses. It is the Ummu’l-Quran, “the essence of the Quran.” God is referred to as the Creator of the “seven heavens” (Surahs Al-Mulk LXVII:3 and Nuh LXXl:15). Hell has “seven gates” dividing seven categories of sinners (Al-Hijr XV:44). Tawaf, circling seven circles around the Holy Kabah is obligatory for the pilgrim to Makkah during Hajj. In Indian Islam the number seven heads the cluster of numbers, 786, derived from numerology and interpreted as “In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.”

Analysis: lslam and Tribal Custom

But we still have to explain the central position of fire in an Islamic tribe. Clearly, any ritual involving fire in Islam has to be imported, for, as in the monotheistic Judaic religions from which Islam claims descent, fire is subordinate to God’s will. When commanded by God it burns, as in Hell, but loses its property when ordered by the Divine, as in the cases of the prophets Moses and Abraham. So, The Book of Common Prayer talks of the “celestial fire”; it has magical properties and does not always burn: “Behold, the bush burned with fire and the bush was not consumed” (The Old Testament, Exodus 3:1-2). Prophets cast into flames have survived unscathed.

So, whereas the application of the number seven—prominent, we noted, in the Bugti fire ritual—is within the orbit of Islamic mythology, fire is not. To justify the employment of fire in a central ritual it is therefore imperative for a Muslim group to “Islamicise” the ritual. Hence the presence of the Holy Quran, the references to the ritual as an Islamic mode of justice, etc.

As the Political Agent of the Agency observed in his special report on the subject: “The philosophy behind the custom is said to be religious, i.e., belief in the Quran and its sanctity. The Holy Quran’s seven rounds over the trench gets the idea from ‘Tawaaf’ around ‘Khana e-Kaaba’, where seven rounds are made. Bugtis are of the opinion that if man is innocent then the Holy Quran will come to his rescue and will not allow fire to burn his feet.” (Haroon 1986:7)

For the Bugti, then, the fusion of a pre-Islamic ritual and the Islamic text is clearly designed to free him of ambiguity and dilemmas regarding the ritual. Nonetheless, as we saw, the ritual is seen as “anti-Islamic” by many Bugtis. Indeed, they point out that the core of the ritual, the invocation or oath, is to the fire and only incidentally to the Holy Quran. The use of the Holy Quran disguises but does not conceal the non-Islamic nature of the ritual.

Why does a Bugti agree to undergo the ordeal? First, in contrast with the lengthy and complicated official court procedures, the Nawab’s support of the ordeal ensures quick justice. “The Nawab last year solved about 250 cases in just over a week on his visit to the Agency—something the official courts would have taken years over,” said Arjun Das Bugti. Second, it represents traditional and customary justice. So strong is their faith in the ritual—and fear of fire—that many accused confess to the crime before the trial. It also underlines Bugti ethnicity both to themselves and to nonBugtis. It portrays honour and tradition, notably in the clause regarding the trial of women. It acts as a key diacritical feature in changing times. Third, it reflects the cohesiveness of the tribe through their customs; it also underlines the central role of the Nawab. Finally, by interspersing Islamic words and features, Bugti belief in the ritual is reinforced; a pre-Islamic custom is transformed into an Islamic one. It is khuda ki shan, the Glory of God proving the power of kalam-i-ilahi, the Holy Quran, they say. The conjunction of a particularistic tribal ritual and a universal religion helps to resolve the tension between the two as it perpetuates that very tension.

Administrators looked on the ritual disapprovingly, seeing it as assisting to erode the government’s authority and its hold over the Bugtis and their area. Indeed, the authorities we have observed trace the origin of the ritual—incorrectly—to the Nawab (as did the Political Agent in his report in 1986). The Ministry of Interior regularly admonished the Government of Balochistan regarding “the activities of the Nawab Akbar Bugti.” Official correspondence described the fire ordeal as a means to intimidate opponents of the Nawab and those inclined to co-operate with the government. Intelligence agencies, with their headquarters in Islamabad, took an equally jaundiced view of the ritual.

The Political Agent summed up the official view in his special report on the fire ritual which I had asked him to prepare:

“Government will lose its grip if things continue. The suggestion in this regard is that the Government of Balochistan should immediately prohibit this practice so that cases are decided on merit. This act will not only help Government in strengthening their grip over the area but will also relieve the general public from this evil practice of outdated system” (Haroon 1986:18).

In conclusion, we note that, although it was considered barbarism by the outside world, a symbol of the Nawab’s power over his tribe by the government, a matter of ethnic honour and identity by some Bugtis—of shame by others—the ritual had survived among the Bugti. However, it was apparent that once the central dominating position of the Nawab was removed from the tribe, the ritual would decline. The survival of tribal rituals into our modern times is the result not only of the will of a powerful chief determined to maintain tribal cohesion—the quest for lbn Khaldun’s asabiyah—but also a combination of other factors which include material expectations in changing times. Moreover, education, political changes, media influences from the rest of Pakistan, a younger generation anxious to re-define itself and the processes of Pakistani nationalism, and larger Islamic revivalism all pose a serious challenge to the ritual.

Elections in Pakistan, opposition parties promising change within the Agency and perhaps most significantly, the death of the Nawab and the vacuum it has caused in the tribe, suggest that the fire ritual is now a thing of the past. It nonetheless allows us important insights into tribal society and its cultural and social mores. Alternative mechanisms may have to be located to maintain ethnic identity and boundaries. The quest for particularism in a world that is heading towards uniformity will pose a central problem to the Bugtis in the 21st century.

With all these changes I am curious about the fate of the fire ritual. It would be worthwhile for the sake of knowledge therefore for contemporary social scientists, especially Baloch scholars, to investigate the current position of the fire ritual among the Bugti. If it has disappeared or has been relegated to invisibility, what has replaced it? Can Malik Siraj Akbar, originally from Makran and currently in Washington DC, persuade someone from the excellent group of scholars and colleagues on his Ink and Insight website to take up the challenge?

By way of post-script: the ruling elite of Pakistan needs to better understand Baloch culture and history with empathy. It must not dismiss local custom, for example the fire ritual, as barbaric and anti-Islamic before attempting to understand its history and role in society. It must never forget that Pakistan cannot survive without Balochistan which constitutes almost half of Pakistan’s land territory, and that Balochistan without Pakistan can thrive on its own. Pakistan must therefore do everything to compensate for the stepchild treatment meted out to Balochistan and ensure that the litany of grievances—the disappearances, the economic disparity, the cultural humiliation etc—is redressed.