Pakistan often calls for border management with Afghanistan to cap the flow of militants along the porous strips. Indeed, on June 20, the Pakistani army issued a statement saying that the first phase of fencing on the international boundary will focus on the Bajaur, Mohmand, and Khyber tribal regions, which are seen as vulnerable to cross-border infiltration by militant groups. The army said new forts and border posts are part of the plan to increase surveillance. Pakistan sees this as essential for “enduring peace and stability”. On June 22, Ambassador Maleeha Lodhi also told the UN that they had started “monitoring vulnerable sections” of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

Afghanistan is not as enthused. The Associated Press quoted Najib Danish, the deputy spokesman for Afghanistan’s Interior Ministry, as saying, “Pakistan has no right to fence or construct any building along the border with Afghanistan.”

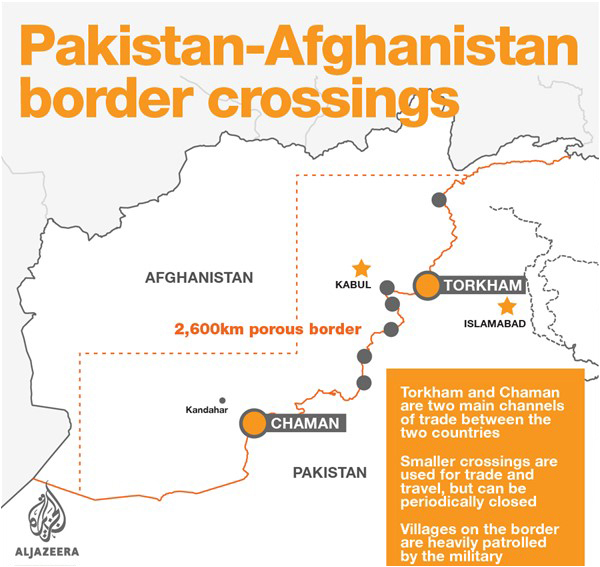

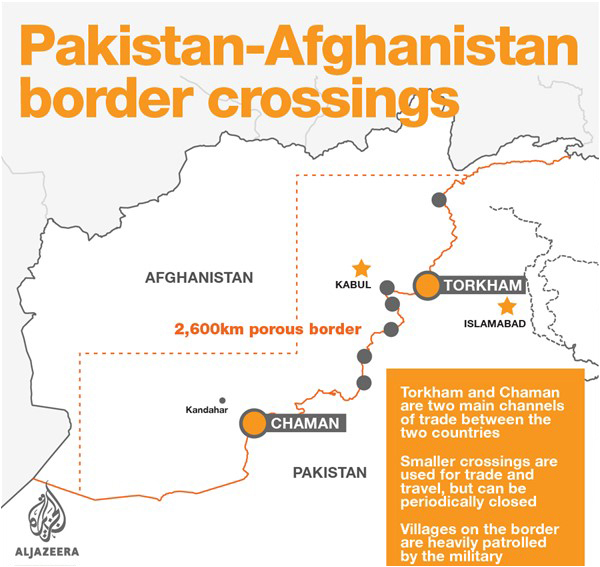

Pakistan and Afghanistan share a border of roughly 2,500kms, which runs through a mountainous terrain and remains largely unmanned.

On May 5 an exchange of fire in which 15 people lost their lives was reported in Chaman after which Bab-e-Dosti was closed. The border was reopened May 27 for Ramadan on humanitarian grounds. This incident indicates, however, that much more is at stake for the border. Pakistan maintains that its census staff, performing its job in bordering villages, came under fire in its territory from the Afghan side. Pakistan argued that heads of the villages say that they are a part of Pakistan. Across the border, however, Afghan officials maintained that Pakistani census staff had encroached on their territory.

What if both countries were correct in their own right?and this is a case of a misunderstanding of territory? Could we consider, perhaps, that this could have been something other than an intentional breach by both sides? If we draw this supposition, then other skirmishes along the border can be seen in a different light. In fact, Chaman was not a one-off incident. Many other skirmishes have been reported in what are typically being described as “cross-border firing”. A few months earlier, in February nearly 100 people were killed in a series of attacks, leading to a month-long closure. Just last year, a Pakistani major was martyred in the Torkham border area in one such firing incident. Earlier, in 2003, in a major diplomatic crisis, the Pakistani embassy came under attack by protesters in Kabul after skirmishes were reported along the border in Mohmand Agency.

A news report by The Guardian in the aftermath of the Salala attack, in which NATO troops fired upon Pakistani military, quoted a senior US military official as admitting to inconsistencies in different maps in “multiples of kilometres.” (This is not to suggest that this specific attack can be solely pegged to inconsistencies) The broad point is his admission that there are gaps. Consider this:

In 2005, a Pakistani military officer, Lt. Colonel Tariq Mahmood, wrote a graduate thesis on the Durand Line at the Naval Postgraduate College in California. He wrote specifically that, “[t]he inadequacies in demarcation of the Durand Line, particularly in Mohmand and Waziristan areas, have resulted in claims and counter claims on each other’s territories.” This position has been brought up by former ambassador Mian Sanaullah, who divides his time with a think tank hosting Pakistan-Afghanistan dialogue. He agrees there are “grey areas” in the border area, but he suggests that no one is ready to investigate it.

Some Pakistani officials have conceded this reality, albeit indirectly. In June 2016, Defence Minister Khawaja Asif, while sharing a policy statement on managing the border, revealed in the Senate that the possibility of making an “adjustment” cannot be ruled out, so as to make the border “permanent”. He even defended former COAS General Raheel Sharif’s decision to hand over a border check post in South Waziristan to Afghanistan as a “goodwill gesture”. Ending these grey areas, or at least acknowledging their presence, could contribute significantly in closing at least one avenue of mistrust.

When Pakistan talks of managing the border it usually means tightening it by installing fences; in some places in Balochistan, including along Chaman, a trench has been dug. This method of “broad management” has become a cliché that is thrown about almost reflexively by Pakistani policymakers, as a solution to any violent incident involving people from either side.

Tightening the border by this method has its critics, who question if it is practical, let alone permissible. They cite the two-way flow of people and goods that are guaranteed under rights and statutes. There are provisions that have to be considered for the divided tribal people and trade for landlocked Afghanistan. To them, cross-border skirmishes raise doubt that tightening the border would serve any purpose. After all, the recent exchange of fire did not involve militants, a presumption behind building fences or trenches. This time it involved professional soldiers.

In Pakistan, any negative response from Afghanistan towards border management (read fencing, trenching) raises alarm bells that it is still not ready to accept the border. A section of society sees border skirmishes as deliberate attempts by either side to challenge the other; in Pakistan, they evoke primordial fears of Afghanistan being bent on undoing the boundary or seceding part of the land.

Arguably, the two countries can explore other options. After the Chaman shooting, the two countries did agree to a joint geological survey to ascertain which side the contesting villages fell on and explore a space for cooperation.

In some ways, this mechanism could offer both sides some face-saving. A thorough inquiry may even reveal that their fears are unfounded. Even if Afghanistan is not ready at this stage to publicly accept the Durand Line as boundary, a call Pakistan has been making, it does have a sense of its geographical limitation that is not that different than that very boundary. And that is what diplomats from both sides need to bank on. Influential Afghan media use the term “de facto border” with reference to the site of the survey.

There have been several foreign-led border management initiatives. From 2007 onwards, Canada conducted a series of workshops, involving Afghan and Pakistani officials, leading into the Dubai Process, which suggested a mechanism along the border to check the flow of people and activities not politically contested. In 2008, the United States helped established a border coordination centre, falling in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar and Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Only recently, in January 2017, after the border was closed after last year’s firing, the British called for a multi-player engagement to address any grievances.

To be clear though, these initiatives could not completely abolish cross-border firing. The American initiative was lost to the Salala attack, and the Chaman incident occurred amid the recently installed British mechanism.

Many may argue, and rightly so, that the issue is about trust. Perhaps that is why the recently installed British mechanism calls for interaction among multiple stakeholders from both sides.

The writer is a researcher based in Islamabad

Afghanistan is not as enthused. The Associated Press quoted Najib Danish, the deputy spokesman for Afghanistan’s Interior Ministry, as saying, “Pakistan has no right to fence or construct any building along the border with Afghanistan.”

Pakistan and Afghanistan share a border of roughly 2,500kms, which runs through a mountainous terrain and remains largely unmanned.

On May 5 an exchange of fire in which 15 people lost their lives was reported in Chaman after which Bab-e-Dosti was closed. The border was reopened May 27 for Ramadan on humanitarian grounds. This incident indicates, however, that much more is at stake for the border. Pakistan maintains that its census staff, performing its job in bordering villages, came under fire in its territory from the Afghan side. Pakistan argued that heads of the villages say that they are a part of Pakistan. Across the border, however, Afghan officials maintained that Pakistani census staff had encroached on their territory.

What if both countries were correct in their own right?and this is a case of a misunderstanding of territory? Could we consider, perhaps, that this could have been something other than an intentional breach by both sides? If we draw this supposition, then other skirmishes along the border can be seen in a different light. In fact, Chaman was not a one-off incident. Many other skirmishes have been reported in what are typically being described as “cross-border firing”. A few months earlier, in February nearly 100 people were killed in a series of attacks, leading to a month-long closure. Just last year, a Pakistani major was martyred in the Torkham border area in one such firing incident. Earlier, in 2003, in a major diplomatic crisis, the Pakistani embassy came under attack by protesters in Kabul after skirmishes were reported along the border in Mohmand Agency.

A news report by The Guardian in the aftermath of the Salala attack, in which NATO troops fired upon Pakistani military, quoted a senior US military official as admitting to inconsistencies in different maps in “multiples of kilometres.” (This is not to suggest that this specific attack can be solely pegged to inconsistencies) The broad point is his admission that there are gaps. Consider this:

In 2005, a Pakistani military officer, Lt. Colonel Tariq Mahmood, wrote a graduate thesis on the Durand Line at the Naval Postgraduate College in California. He wrote specifically that, “[t]he inadequacies in demarcation of the Durand Line, particularly in Mohmand and Waziristan areas, have resulted in claims and counter claims on each other’s territories.” This position has been brought up by former ambassador Mian Sanaullah, who divides his time with a think tank hosting Pakistan-Afghanistan dialogue. He agrees there are “grey areas” in the border area, but he suggests that no one is ready to investigate it.

Some Pakistani officials have conceded this reality, albeit indirectly. In June 2016, Defence Minister Khawaja Asif, while sharing a policy statement on managing the border, revealed in the Senate that the possibility of making an “adjustment” cannot be ruled out, so as to make the border “permanent”. He even defended former COAS General Raheel Sharif’s decision to hand over a border check post in South Waziristan to Afghanistan as a “goodwill gesture”. Ending these grey areas, or at least acknowledging their presence, could contribute significantly in closing at least one avenue of mistrust.

When Pakistan talks of managing the border it usually means tightening it by installing fences; in some places in Balochistan, including along Chaman, a trench has been dug. This method of “broad management” has become a cliché that is thrown about almost reflexively by Pakistani policymakers, as a solution to any violent incident involving people from either side.

Tightening the border by this method has its critics, who question if it is practical, let alone permissible. They cite the two-way flow of people and goods that are guaranteed under rights and statutes. There are provisions that have to be considered for the divided tribal people and trade for landlocked Afghanistan. To them, cross-border skirmishes raise doubt that tightening the border would serve any purpose. After all, the recent exchange of fire did not involve militants, a presumption behind building fences or trenches. This time it involved professional soldiers.

To critics, cross-border skirmishes raise doubt that further tightening the border would serve any purpose. After all, the recent exchange of fire did not involve militants, a presumption behind building fences or trenches. This time it involved professional soldiers

In Pakistan, any negative response from Afghanistan towards border management (read fencing, trenching) raises alarm bells that it is still not ready to accept the border. A section of society sees border skirmishes as deliberate attempts by either side to challenge the other; in Pakistan, they evoke primordial fears of Afghanistan being bent on undoing the boundary or seceding part of the land.

Arguably, the two countries can explore other options. After the Chaman shooting, the two countries did agree to a joint geological survey to ascertain which side the contesting villages fell on and explore a space for cooperation.

In some ways, this mechanism could offer both sides some face-saving. A thorough inquiry may even reveal that their fears are unfounded. Even if Afghanistan is not ready at this stage to publicly accept the Durand Line as boundary, a call Pakistan has been making, it does have a sense of its geographical limitation that is not that different than that very boundary. And that is what diplomats from both sides need to bank on. Influential Afghan media use the term “de facto border” with reference to the site of the survey.

There have been several foreign-led border management initiatives. From 2007 onwards, Canada conducted a series of workshops, involving Afghan and Pakistani officials, leading into the Dubai Process, which suggested a mechanism along the border to check the flow of people and activities not politically contested. In 2008, the United States helped established a border coordination centre, falling in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar and Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Only recently, in January 2017, after the border was closed after last year’s firing, the British called for a multi-player engagement to address any grievances.

To be clear though, these initiatives could not completely abolish cross-border firing. The American initiative was lost to the Salala attack, and the Chaman incident occurred amid the recently installed British mechanism.

Many may argue, and rightly so, that the issue is about trust. Perhaps that is why the recently installed British mechanism calls for interaction among multiple stakeholders from both sides.

The writer is a researcher based in Islamabad