June 26 marks the international day against drug abuse and illicit trafficking but its focus is often the needle in the arm. What is worth talking about this year is how drug traffickers remit millions of rupees from bank accounts maintained in various countries in fictitious names. This money in the hands of drug traffickers has made them invincible.

According to James Petras, Professor of Sociology, Binghamton University, New York, there is a consensus among US congressional investigators, former bankers and international banking experts that the US and the European banks launder between $500 billion and $1 trillion of dirty money each year, half of which is laundered by US banks alone. The estimates are based on reports published by the US State Department every year called the International Drug Control Strategy Report.

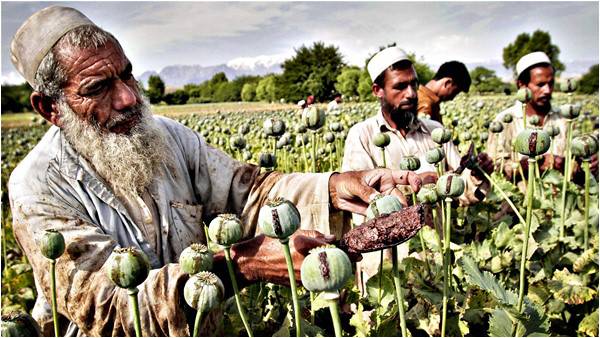

At the political level, the threat from drugs is even more serious. In Afghanistan the US and NATO forces have been claiming to fight a war to eradicate opium but production has increased manifold as confirmed in the International Narcotics Control Strategy Report 2017.

In 2006, Pakistan had 4.5 million drug addicts and the number is expected to now be nearly nine million. In the international drug market, the share of Pakistani mafia is around US$30 billion to $40 billion. In Pakistan, there have been many instances when drug barons have managed to become members of the provincial and National assemblies. Drug money has played an important role in no-confidence motions in securing support for the passage of important bills—especially during 1990-1995, when neither the Nawaz Sharif nor the Benazir Bhutto governments had a clear majority. The drug money was used in securing laws like the Protection of Economic Reforms Act 1992 so that drug barons could easily hide and whiten their dirty money. An amendment was also made in section 111 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 1979 so that no question could be asked if money is parked in foreign currency accounts and remitted from outside.

The evidence of politicians involved in drug trade was documented in the International Narcotics Control Strategy Report released by the US State Department in 1999: “The prosecution of prominent drug offenders Sakhi Dost, Jan Notezai, and Munawar Hussain Manj continued to drag out in the courts. Manj is an ex-member of Pakistan’s National Assembly. He was arrested on drug charges in April 1995. His case is being tried in the court of the additional session judge in Lahore. The accused applied for bail, which was rejected by the Supreme Court. Defense attorneys were successful in delaying court proceedings. Notezai is a member of a politically and economically prominent family in Balochistan. His case has been pending in the courts since 1993. In 1998, Notezai’s appeal to the Supreme Court for a new trial was rejected, which cleared the way for a lower court in Quetta to conclude the trial. Earlier the Balochistan High Court rejected the same appeal. The decision by the Supreme Court prompted Notezai to appeal to the Federal Shariat (Muslim Law) Court for a ‘de novo’ trial, a request that was denied on July 2, 1999. Meanwhile, on establishment of a district court at Nushki the case has been transferred to a sessions judge there and further delayed.”

The former private banker, Antonio Giraldi, in a testimony before the Senate sub-committee projects significant growth in the US bank laundering. “The forecasters also predict the amounts laundered in trillions of dollars and growing disproportionately to legitimate funds.” The $500 billion of criminal and dirty money flowing into and through the major US banks far exceeds the net revenues of all the IT companies in the US, not to speak of their profits.

John Reed, chairman and co-CEO of Citigroup, in his testimony before the Senate said: “I appear today with Todd Thompson, who became the head of our private bank about ten days ago, and Mark Musi, the head of the private bank’s Compliance and Control Department. Unfortunately, Shaukat Aziz, who ran the private bank for the last two years and under whose leadership many of the improvements in our private bank’s anti-money laundering programs took place, cannot participate in these hearings. Mr. Aziz would really have been the most appropriate witness today, given his experience and knowledge but as you know, he was called home to serve his country, Pakistan, as Minister of Finance. He left the Bank on October 29. He asked me to submit his statement for the record, and it is attached to my own all financial institutions … whether banks, securities firms, or other types of financial intermediaries are potentially vulnerable to money laundering.”

Shaukat Aziz was assigned the task of suggesting new rules and regulations in the wake of the BCCI case in which drug money and its transmission through the bank was established. It was a significant hearing before the US Congress Subcommittee that he had to attend but he left for Pakistan before it to become finance minister and his subordinate presented the report. Later when he became finance minister and then prime minister he did not revoke laws that help money laundering in Pakistan.

Today, all the big US banks have multiple correspondent relationships throughout the world so that they may engage in international financial transactions for themselves and their clients in places where they do not have a physical presence. Many of the largest US and European banks located in the financial centres of the world serve as correspondents for thousands of other banks. Most of the offshore banks laundering billions for criminal clients have accounts in the US. All the big banks specialising in international fund transfers are called money centre banks, and some of the biggest ones process up to $1 trillion in wire transfers a day. For billionaire criminals an important feature of correspondent relationships is that they provide access to international transfer systems that facilitate the rapid transfer of funds across international boundaries and within countries. The most recent estimates are that 60 offshore jurisdictions around the world licensed about 4,000 offshore banks that control approximately $35 trillion in assets.

This is the situation on the ground whereas we observe the official quarters in the US and elsewhere making big claims daily about the war against drugs and terrorism. In reality all the financial institutions and State structure are subservient to these billionaires, the drug barons, who know how to move money from one part of the world to another, buy government functionaries, control the politicians, law-enforcement officials and get the profits they want from the drug trade.

The writers, lawyers and authors, have studied linkages between drug trade and terrorist financing and social effects of drug abuse. They are author of many articles on these issues and authors of two books, Pakistan: From Hash to Heroin and its sequel Pakistan: Drug-trap to Debt-trap

According to James Petras, Professor of Sociology, Binghamton University, New York, there is a consensus among US congressional investigators, former bankers and international banking experts that the US and the European banks launder between $500 billion and $1 trillion of dirty money each year, half of which is laundered by US banks alone. The estimates are based on reports published by the US State Department every year called the International Drug Control Strategy Report.

At the political level, the threat from drugs is even more serious. In Afghanistan the US and NATO forces have been claiming to fight a war to eradicate opium but production has increased manifold as confirmed in the International Narcotics Control Strategy Report 2017.

In 2006, Pakistan had 4.5 million drug addicts and the number is expected to now be nearly nine million. In the international drug market, the share of Pakistani mafia is around US$30 billion to $40 billion. In Pakistan, there have been many instances when drug barons have managed to become members of the provincial and National assemblies. Drug money has played an important role in no-confidence motions in securing support for the passage of important bills—especially during 1990-1995, when neither the Nawaz Sharif nor the Benazir Bhutto governments had a clear majority. The drug money was used in securing laws like the Protection of Economic Reforms Act 1992 so that drug barons could easily hide and whiten their dirty money. An amendment was also made in section 111 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 1979 so that no question could be asked if money is parked in foreign currency accounts and remitted from outside.

The evidence of politicians involved in drug trade was documented in the International Narcotics Control Strategy Report released by the US State Department in 1999: “The prosecution of prominent drug offenders Sakhi Dost, Jan Notezai, and Munawar Hussain Manj continued to drag out in the courts. Manj is an ex-member of Pakistan’s National Assembly. He was arrested on drug charges in April 1995. His case is being tried in the court of the additional session judge in Lahore. The accused applied for bail, which was rejected by the Supreme Court. Defense attorneys were successful in delaying court proceedings. Notezai is a member of a politically and economically prominent family in Balochistan. His case has been pending in the courts since 1993. In 1998, Notezai’s appeal to the Supreme Court for a new trial was rejected, which cleared the way for a lower court in Quetta to conclude the trial. Earlier the Balochistan High Court rejected the same appeal. The decision by the Supreme Court prompted Notezai to appeal to the Federal Shariat (Muslim Law) Court for a ‘de novo’ trial, a request that was denied on July 2, 1999. Meanwhile, on establishment of a district court at Nushki the case has been transferred to a sessions judge there and further delayed.”

The former private banker, Antonio Giraldi, in a testimony before the Senate sub-committee projects significant growth in the US bank laundering. “The forecasters also predict the amounts laundered in trillions of dollars and growing disproportionately to legitimate funds.” The $500 billion of criminal and dirty money flowing into and through the major US banks far exceeds the net revenues of all the IT companies in the US, not to speak of their profits.

In the international drug market, the share of Pakistani mafia is around US$30 billion to $40 billion. The champions of "democracy" and "freedom" do not mind such dirty money at home, but impose restrictions on others to stop all kinds of money laundering operations

John Reed, chairman and co-CEO of Citigroup, in his testimony before the Senate said: “I appear today with Todd Thompson, who became the head of our private bank about ten days ago, and Mark Musi, the head of the private bank’s Compliance and Control Department. Unfortunately, Shaukat Aziz, who ran the private bank for the last two years and under whose leadership many of the improvements in our private bank’s anti-money laundering programs took place, cannot participate in these hearings. Mr. Aziz would really have been the most appropriate witness today, given his experience and knowledge but as you know, he was called home to serve his country, Pakistan, as Minister of Finance. He left the Bank on October 29. He asked me to submit his statement for the record, and it is attached to my own all financial institutions … whether banks, securities firms, or other types of financial intermediaries are potentially vulnerable to money laundering.”

Shaukat Aziz was assigned the task of suggesting new rules and regulations in the wake of the BCCI case in which drug money and its transmission through the bank was established. It was a significant hearing before the US Congress Subcommittee that he had to attend but he left for Pakistan before it to become finance minister and his subordinate presented the report. Later when he became finance minister and then prime minister he did not revoke laws that help money laundering in Pakistan.

Today, all the big US banks have multiple correspondent relationships throughout the world so that they may engage in international financial transactions for themselves and their clients in places where they do not have a physical presence. Many of the largest US and European banks located in the financial centres of the world serve as correspondents for thousands of other banks. Most of the offshore banks laundering billions for criminal clients have accounts in the US. All the big banks specialising in international fund transfers are called money centre banks, and some of the biggest ones process up to $1 trillion in wire transfers a day. For billionaire criminals an important feature of correspondent relationships is that they provide access to international transfer systems that facilitate the rapid transfer of funds across international boundaries and within countries. The most recent estimates are that 60 offshore jurisdictions around the world licensed about 4,000 offshore banks that control approximately $35 trillion in assets.

This is the situation on the ground whereas we observe the official quarters in the US and elsewhere making big claims daily about the war against drugs and terrorism. In reality all the financial institutions and State structure are subservient to these billionaires, the drug barons, who know how to move money from one part of the world to another, buy government functionaries, control the politicians, law-enforcement officials and get the profits they want from the drug trade.

The writers, lawyers and authors, have studied linkages between drug trade and terrorist financing and social effects of drug abuse. They are author of many articles on these issues and authors of two books, Pakistan: From Hash to Heroin and its sequel Pakistan: Drug-trap to Debt-trap