In these days of climate change and ecological conservation movements, it is important to see living beings as being more than just objects. Though they may not have brains and move or grow slowly, they play their own unique role in our ecosystem. Their lives are interconnected to us through the natural way of coexisting on the planet.

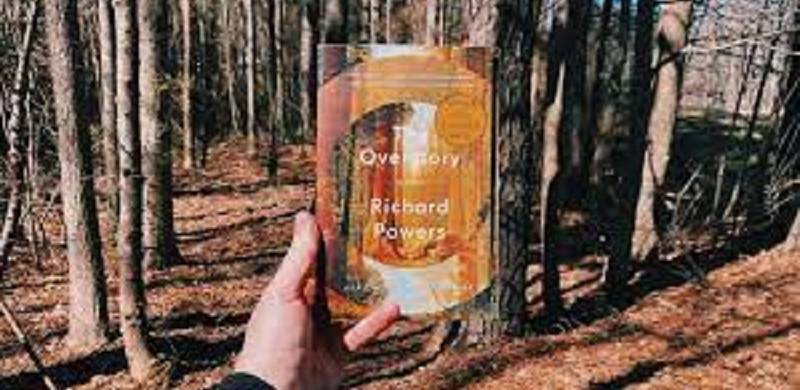

Spurred by the novel Overstory by Richard Powers in my monthly book club in Washington DC, we spoke about trees and their significance in their lives. Powers won the Pulitzer Prize in 2019 and used a series of disconnected short stories to weave together the importance of trees over time, space and across generations.

This interesting conversation meandered what role trees played in our youth and sense of memory. One lady recorded her journey back to her grandfather’s old plot of land which was sold to the state when the government created the famous Redwood forests in California. Another recounted climbing up a cherry tree in her youth and being able to have cherry pie made for her summer birthday. Yet another remembered how her young twins used to climb up magnolia trees and how distressed she was when they were chopped down to make way for an underground car-park.

German forester Peter Wohleben writes powerfully about this in his book The Hidden Life of Trees. He refers to trees as having a sophisticated silent language

My childhood memories were of magnificent banyan trees in Karachi and Lahore. Banyans generously spread their branches to provide shade during the hot day and then at sunset shelter flocks of twittering birds. Banyans never sleep which is perhaps why in many cultures they are deemed sacred.

Science teaches us that trees are an essential part of our ecosystem. They store carbon dioxide and release oxygen into the air. A fully grown tree can produce enough oxygen for up to 20 humans a year. More than this functionality, trees represent different things in diverse cultures and religions.

The Garden of Eden is an allegory of the world, and the Tree of Life a symbol of Nature’s fecundity – except its fruit was not to nourish the body but food for the mind through knowledge of good and evil. Trees were not only highly regarded in Christianity but have a central place in other religions. In Buddhism, for example, the Bodho tree was believed to induce enlightenment and has been revered since as a symbol of Buddha. Even in children’s literature, Enid Blyton’s book The Magic Tree allows for a magical resting place for many adventures.

During the pandemic, we found a tree growing on our roof. Seeds transported by the wind or carried by birds had fallen on the roof and germinated. Trees provide cover – both for the wild life and animals that live in them but also for people to sit under their shade, particularly in hot climates. Many group meetings are held under trees, whether jirgas in our part of the world or the panchayat in India or even under the baobab trees in Senegal. Trees may be immobile but they are nevertheless living creatures. Though rooted in the ground and earth but are also part of the sky and natural elements – taking and giving back to the universe in turn. They are ancient symbols of fertility and ancestry – growing over generations and spawning new life. The branches often represented in art and literature symbolize different generations. Our own growth over life is like these branches, each breaking away to follow its own path, to grow separately yet connected with the trunk of humanity.

German forester Peter Wohleben writes powerfully about this in his book The Hidden Life of Trees. He refers to trees as having a sophisticated silent language, communicating complex information via smell, taste, and electrical impulses. Who would have thoughts that trees pass wisdom down to the next generation through their seeds, what makes them live so long, and how forests handle migrant trees? In forests, trees are even interconnected like the families and communities that we live in as humans. They support failing trees by providing nutrients. The forest is their family, so much so that solitary trees die before their time. A lone tree cannot maintain a consistent local climate as it falls prey to wind and weather patterns but within an eco-system such as a forest, multiple trees can store water and moderate temperature.

So as we consider how non-human things can be interconnected – be it fluid octopuses or static trees – invest a moment of your life, recall your favourite tree and what it has meant to you, and you will understand why you need to plant as many trees as you can space for, even on your roof!