‘World Nutrition Month’ was celebrated by physicians and nutritionists world-wide this March. Pakistan had little to rejoice as six more infants died of waterborne diseases and malnutrition in Tharparkar, bringing the toll to 72 since January.

Earlier this month, members of the health and science community gathered at the Pakistan Academy of Sciences to discuss maternal and child health, population growth, and water sanitation at a two-day workshop called, “Pakistan’s Challenges of Health and Nutrition in the Context of the SDGs”.

This gathering was a collaborative effort by the World Health Organization (WHO), Ministry of Health, Aga Khan University (AKU) and the Pakistan Academy of Sciences. The aim was to increase awareness on the health and nutrition challenges plaguing Pakistan, and put them within the framework of Pakistan’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) commitments, in particular Goal 3. The workshop’s most tangible outcome was the establishment of an independent consortium, which would work towards monitoring, on federal and provincial levels, Pakistan’s progress in meeting its sustainable development goals on health.

Health and nutrition

Health and nutrition statistics coming out of Pakistan, especially for maternal and child health are alarming. The mother and child are two of the most vulnerable classes, whose lives are at risk due to lack of clean water and hygiene, illiteracy, malnourishment; all of these problems are rooted in multiple inequalities and are deeply connected.

According to Dr Zafar Mirza, convener of WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office SDG Taskforce, the SDGs present the “grandest opportunity” to Pakistan to revamp its healthcare blueprint and provide its citizens with the necessary infrastructure required to actualize good health and well-being.

Malnutrition's inter generational effect

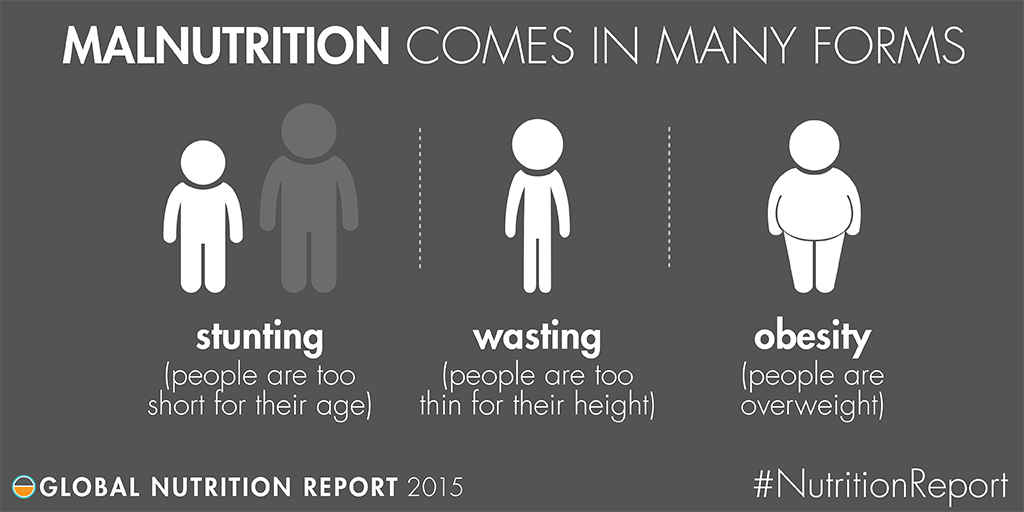

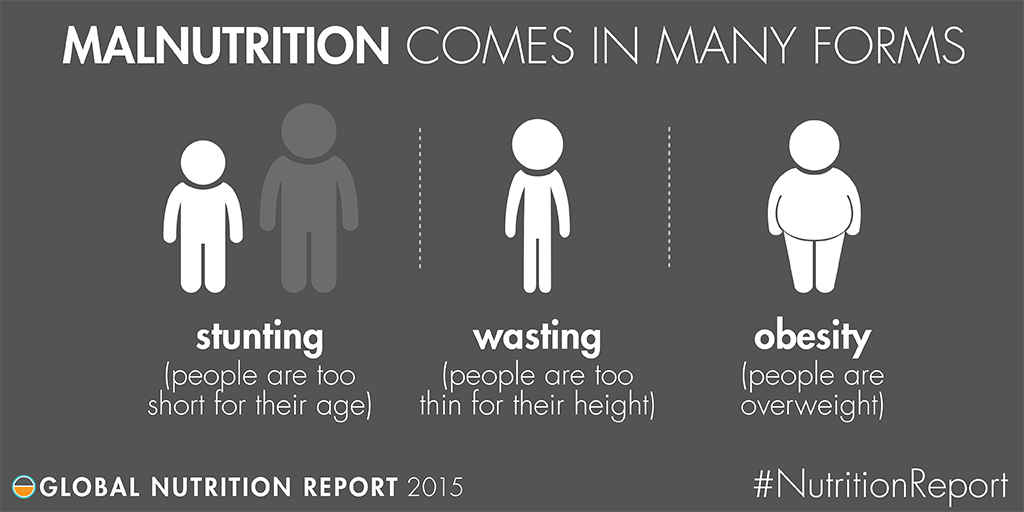

“Health and nutrition of the mother and child are linked, across generations,” said Dr Zulfiqar Bhutta, director of the Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health at AKU. A mother’s malnutrition influences the stunting of her child.

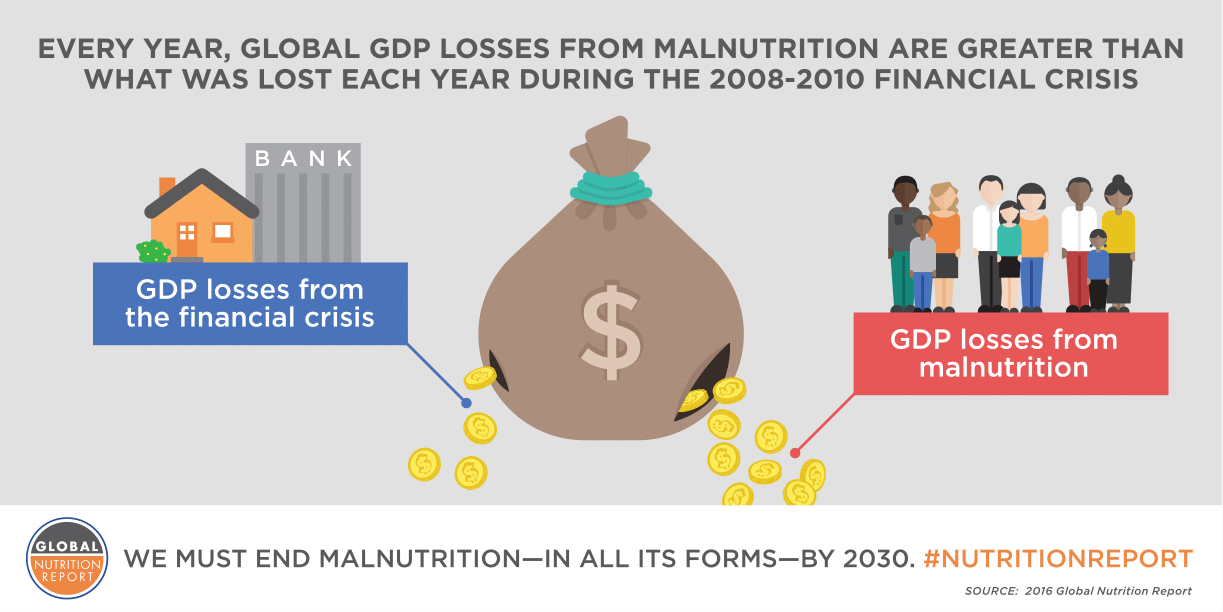

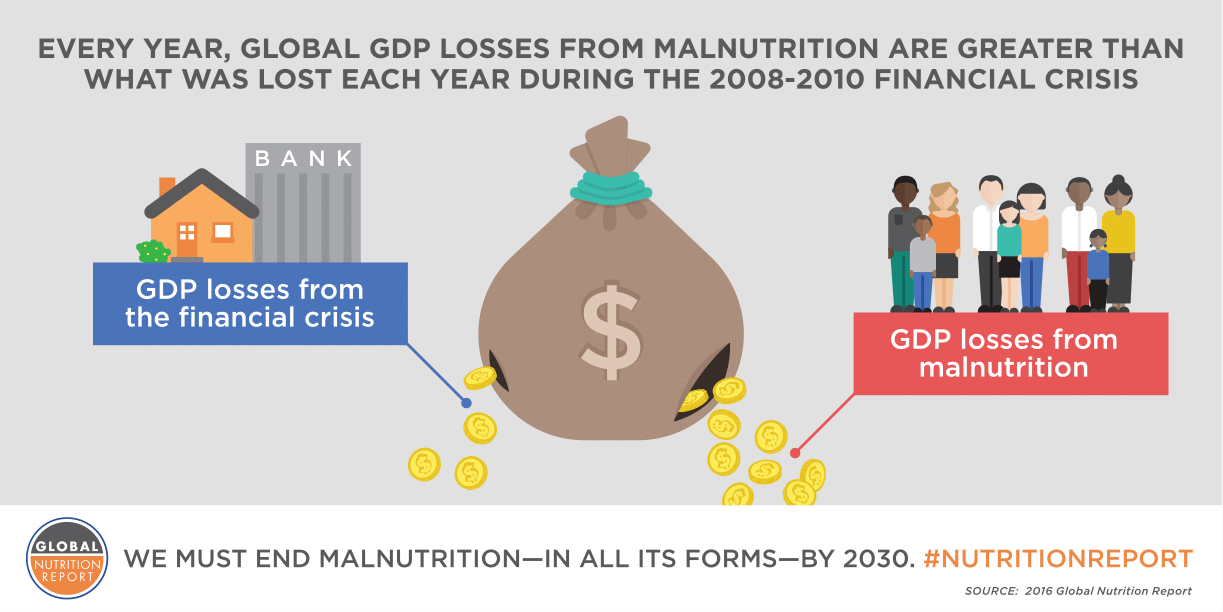

Stunting occurs as a result of chronic malnutrition over a long period of time. If a mother is malnourished, it will affect her child’s growth; from the small size of the baby during pregnancy, to a more long-term effect on the child’s health, performance in school, and future earnings, having an accumulative effect on the economic growth of a country. According to the Global Nutrition Report 2016, the economic consequences of low weight, poor child growth, and micro-nutrient deficiencies represent losses of 11 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) every year in Africa and Asia.

Today, nearly 44 per cent of children in Pakistan are stunted, surpassed only by countries like Yemen, Eritrea, and Timor Leste. In the South Asian region, Pakistan ranks the lowest in terms of its stunting figures. This is catastrophic since stunting is largely irreversible, if not treated.

For Pakistan, the perception of malnutrition is limited to the occasional outcry over children living in abject poverty, in the arid Thar desert. But it would be too simplistic to pair malnutrition with poverty alone. A woman’s power and status have a major influence on the bleak reality of malnutrition in Pakistan. For example, studies have shown that children are less likely to be stunted if their mothers have secondary education, and women who give birth at the age of 18 or below, are more likely to have stunted children (Global Nutrition Report, 2016).

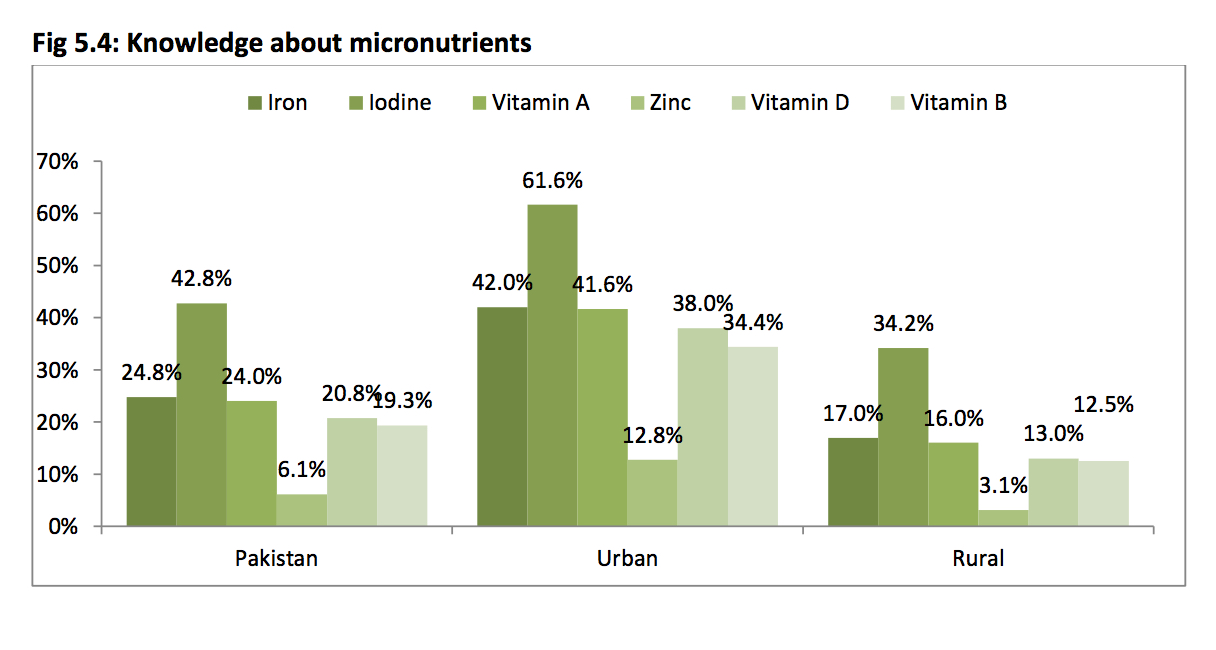

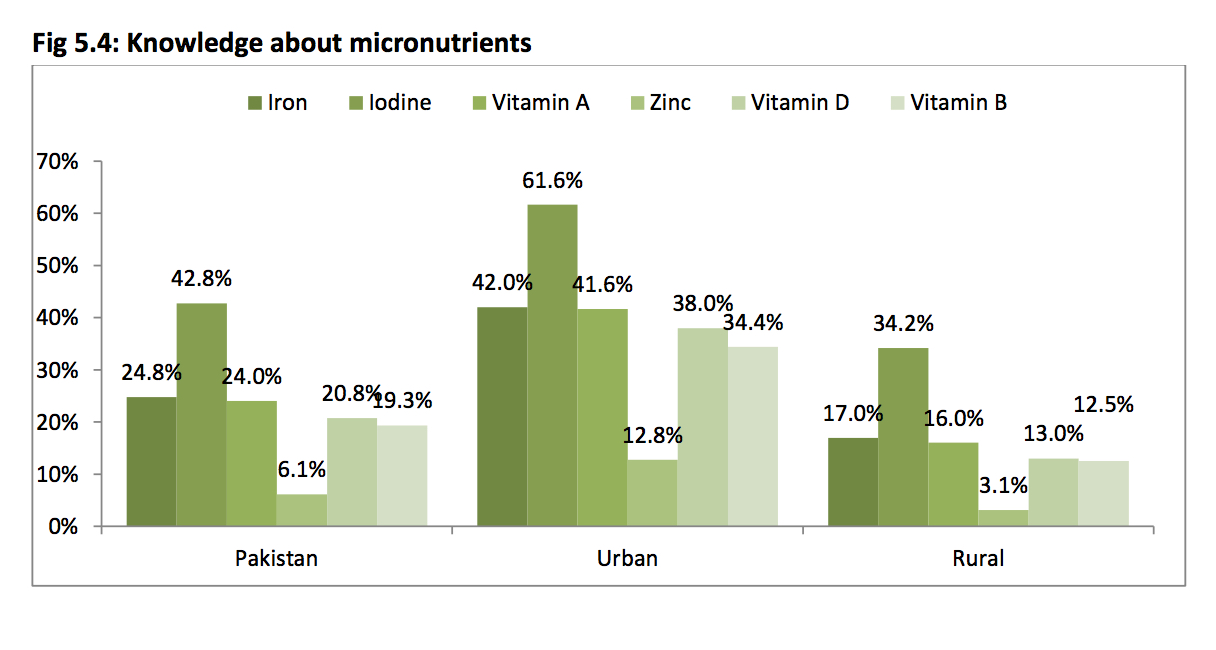

The last national nutrition survey (NNS) held in Pakistan was six years ago. Although a little outdated, the NNS 2011 quite clearly demonstrated the effects of multiple inequalities such as poverty, lack of maternal education and the urban and rural comparisons. Data collected showed that only 24.8% of mothers has knowledge about iron across Pakistan, 42% in urban areas 17% in rural.

The complex relationship between malnutrition and poverty is “strongly influenced by the degree and form of female subjugation, which affects the girl child and women alike,” according to NNS 2011. The basic determinants of maternal and child nutrition, such as maternal education must be addressed.

The complex relationship between malnutrition and poverty is “strongly influenced by the degree and form of female subjugation, which affects the girl child and women alike,” according to NNS 2011. The basic determinants of maternal and child nutrition, such as maternal education must be addressed.

According to Bhutta, in order to curb the endemic issue of malnutrition and stunting, a cross-generational strategy is essential to address social determinants, such as poverty and lack of women’s empowerment.

Water, sanitation and hygiene

More than 40 million Pakistanis defecate in the open. According to the UNICEF, open defecation and lack of sanitation in general, contribute to higher cases of diarrhoea, and intestinal parasites, which in turn cause malnutrition. It is no wonder that 110 children under the age of five die every day from diarrheal-related disease, caused by inadequate access to clean water and sanitation.

Access to water is not only a determinant in the health of the child, but also acts as a social determinant in a woman’s ability to access education.

Goals are linked

A development agenda cannot be pushed on a hungry and malnourished child, and therefore the causes and consequences of malnutrition must be addressed.

Pakistan’s multiple healthcare challenges are multi-sectoral, overlapping significantly as observed in the widespread problems of mother-child malnutrition and access to clean water and toilets. Immense national coordination will therefore be required if we want to make significant gains towards achieving the goal of health and well-being. Similarly, the SDG on health is not only pigeon-holed to SDG 3; conversely, it is linked to all 17 of the sustainable development goals.

“Health is a determinant, indicator, and outcome of the global agenda on sustainable development goals,” says Dr Zafar Mirza, who was the keynote speaker.

Similarly, the inter-linkages between health and poverty, nutrition, quality education and the sexual and reproductive rights of women cannot be understated.

Goal 17, on fostering partnerships, is perhaps the magic adhesive which will prove to be critical in monitoring and attaining our national health agenda. Currently, there is a dissonance underlining Pakistan’s health economy as 70% of Pakistanis opt for healthcare outside the public sector. Subsequently, the role of public-private partnerships in themselves must be examined and strengthened.

The Parliamentary Taskforce on SDGs, headed by Minister of Information and Broadcasting Maryam Aurangzeb will be decisive in leading the process of creating linkages between provincial policies and action plans, usually developed in silos and rarely backed by financial resources, timelines or strong political will.

Axis of multi-sectoral policy

Apart from improving inter-sectoral linkages, policies and legislative instruments that impact issues of health and scientific progress need to be studied, revamped and created anew if required.

According to panellist Dr Zeba Sathar, Country Director of the Population Council, there is a severe scarcity of targeted policies, in Pakistan. “The three nutrition surveys of 1990, 2001 and 2011 all pointed to under nutrition being a major source of economic burden.” Pakistan has yet to formulate an overarching policy on nutrition.

Malnutrition’s links with food insecurity, compounded by Pakistan’s mushrooming population growth, must also be studied to achieve our healthcare targets. The multiple inequalities prevalent within our provinces cannot be overlooked either.

While addressing the issue of population growth in Pakistan, Dr Sathar stated that “no country with Pakistan’s level of development has such a high population rate.” Unfortunately, other than the Punjab Growth Strategy, no policy created up to date has solely addressed the issue of population growth.

Dr Zafar expanded on the “axis of policy coherence” in which vertical development comprised legislative instruments, and horizontal development required comprehensive, evidence-based policies. Enabling legislation is fundamental to bringing Pakistan’s policies and practices in line with achieving the SDGs for health. For example, a short maternity leave policy can have an adverse effect on the nutrition of a child, and therefore it is critical to study the impact of the underlying legislation and ancillary policy.

Data & awareness

According to Dr Zulfiqar Bhutta, the “intergenerational cycle of ill health, stunted growth and gender differentials in opportunities are a huge stumbling block to progress,” and therefore, “optimising maternal and child health is critical for the development of Pakistan.” These words can only be put to practice if we witness a societal change fuelled by evidence-based data and research, so fundamental to achieving mutual accountability. The long-awaited census will hopefully provide us with some elementary data.

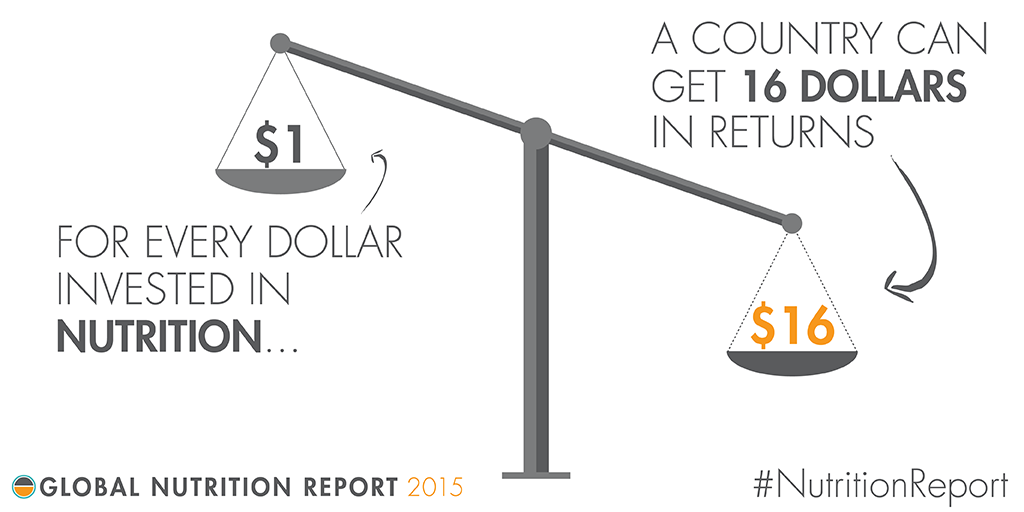

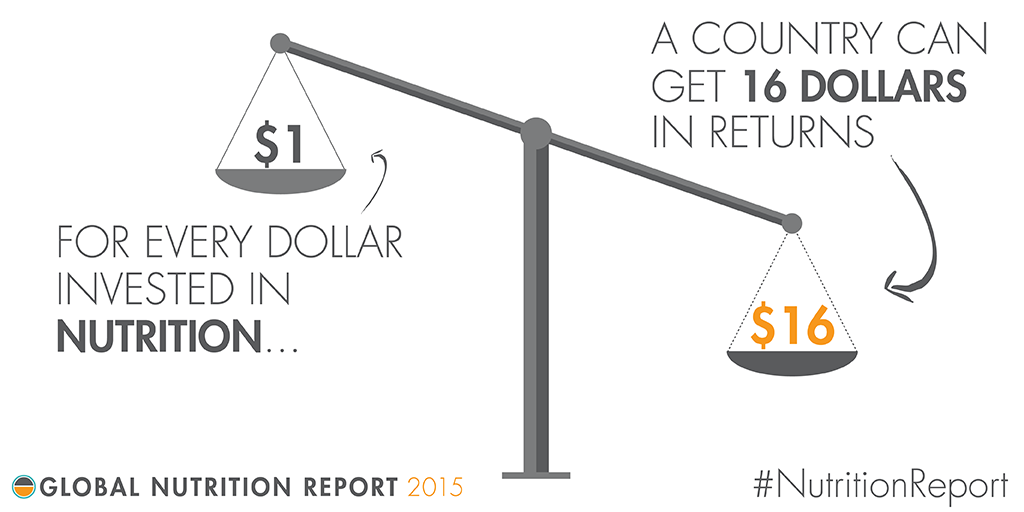

For a country that spends the second lowest per capita on health in the region, things need to change. It is critical that we invest in science at the grassroots level, as the backbone of national development extends beyond roads and bridges.

According to Tim Evans, the Senior Director of Health, Nutrition and Population at the World Bank, “we cannot assume that everyone appreciates the case for health.” He added that “articulating the intrinsic value of health” is therefore a necessary exercise.

Maryam Aurangzeb spoke at length about the government’s role in raising awareness on the SDG health agenda. According to her, a slot will be provided on Radio Pakistan, and PTV, dedicated solely to mainstreaming the sustainable development goals on health. Both the public and private media channels, have the opportunity of playing a huge role in spreading awareness on numerous health and nutrition issues plaguing our country.

Outcomes

The outcome of the workshop was the creation of an independent consortium which would assist and monitor the government’s performance at the federal and provincial levels. The consortium comprising members from the health and science community would also produce an annual report on selected health indicators.

On the face of it, Pakistan has shown leadership in making structural arrangements to further the SDG3 agenda. A Parliamentary Taskforce on the SDGs of national and provincial parliamentarians has been created. Pakistan has also aligned its National Vision 2016-2025 which addresses health, nutrition challenges of the mother and child in accordance with the SDGs.

“Health is not an abstract slogan but a fundamental right,” says Dr Zafar, and now the official policy has been endorsed worldwide. Whilst the expiration of the Millennium Development Goal targets was met with disappointment results for Pakistan, one hopes that we are able to learn our lessons for the future.

** Editor's note: This article has been updated online with a few corrections and images.

The writer is a lawyer. She works at the Public Interest Law Association of Pakistan (Pilap) as their legal counsel. She can be reached at noorzafar7@gmail.com

Earlier this month, members of the health and science community gathered at the Pakistan Academy of Sciences to discuss maternal and child health, population growth, and water sanitation at a two-day workshop called, “Pakistan’s Challenges of Health and Nutrition in the Context of the SDGs”.

This gathering was a collaborative effort by the World Health Organization (WHO), Ministry of Health, Aga Khan University (AKU) and the Pakistan Academy of Sciences. The aim was to increase awareness on the health and nutrition challenges plaguing Pakistan, and put them within the framework of Pakistan’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) commitments, in particular Goal 3. The workshop’s most tangible outcome was the establishment of an independent consortium, which would work towards monitoring, on federal and provincial levels, Pakistan’s progress in meeting its sustainable development goals on health.

Health and nutrition

Health and nutrition statistics coming out of Pakistan, especially for maternal and child health are alarming. The mother and child are two of the most vulnerable classes, whose lives are at risk due to lack of clean water and hygiene, illiteracy, malnourishment; all of these problems are rooted in multiple inequalities and are deeply connected.

According to Dr Zafar Mirza, convener of WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office SDG Taskforce, the SDGs present the “grandest opportunity” to Pakistan to revamp its healthcare blueprint and provide its citizens with the necessary infrastructure required to actualize good health and well-being.

Malnutrition's inter generational effect

“Health and nutrition of the mother and child are linked, across generations,” said Dr Zulfiqar Bhutta, director of the Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health at AKU. A mother’s malnutrition influences the stunting of her child.

Stunting occurs as a result of chronic malnutrition over a long period of time. If a mother is malnourished, it will affect her child’s growth; from the small size of the baby during pregnancy, to a more long-term effect on the child’s health, performance in school, and future earnings, having an accumulative effect on the economic growth of a country. According to the Global Nutrition Report 2016, the economic consequences of low weight, poor child growth, and micro-nutrient deficiencies represent losses of 11 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) every year in Africa and Asia.

Today, nearly 44 per cent of children in Pakistan are stunted, surpassed only by countries like Yemen, Eritrea, and Timor Leste. In the South Asian region, Pakistan ranks the lowest in terms of its stunting figures. This is catastrophic since stunting is largely irreversible, if not treated.

For Pakistan, the perception of malnutrition is limited to the occasional outcry over children living in abject poverty, in the arid Thar desert. But it would be too simplistic to pair malnutrition with poverty alone. A woman’s power and status have a major influence on the bleak reality of malnutrition in Pakistan. For example, studies have shown that children are less likely to be stunted if their mothers have secondary education, and women who give birth at the age of 18 or below, are more likely to have stunted children (Global Nutrition Report, 2016).

The last national nutrition survey (NNS) held in Pakistan was six years ago. Although a little outdated, the NNS 2011 quite clearly demonstrated the effects of multiple inequalities such as poverty, lack of maternal education and the urban and rural comparisons. Data collected showed that only 24.8% of mothers has knowledge about iron across Pakistan, 42% in urban areas 17% in rural.

The complex relationship between malnutrition and poverty is “strongly influenced by the degree and form of female subjugation, which affects the girl child and women alike,” according to NNS 2011. The basic determinants of maternal and child nutrition, such as maternal education must be addressed.

The complex relationship between malnutrition and poverty is “strongly influenced by the degree and form of female subjugation, which affects the girl child and women alike,” according to NNS 2011. The basic determinants of maternal and child nutrition, such as maternal education must be addressed.According to Bhutta, in order to curb the endemic issue of malnutrition and stunting, a cross-generational strategy is essential to address social determinants, such as poverty and lack of women’s empowerment.

Water, sanitation and hygiene

More than 40 million Pakistanis defecate in the open. According to the UNICEF, open defecation and lack of sanitation in general, contribute to higher cases of diarrhoea, and intestinal parasites, which in turn cause malnutrition. It is no wonder that 110 children under the age of five die every day from diarrheal-related disease, caused by inadequate access to clean water and sanitation.

Access to water is not only a determinant in the health of the child, but also acts as a social determinant in a woman’s ability to access education.

Goals are linked

A development agenda cannot be pushed on a hungry and malnourished child, and therefore the causes and consequences of malnutrition must be addressed.

Pakistan’s multiple healthcare challenges are multi-sectoral, overlapping significantly as observed in the widespread problems of mother-child malnutrition and access to clean water and toilets. Immense national coordination will therefore be required if we want to make significant gains towards achieving the goal of health and well-being. Similarly, the SDG on health is not only pigeon-holed to SDG 3; conversely, it is linked to all 17 of the sustainable development goals.

“Health is a determinant, indicator, and outcome of the global agenda on sustainable development goals,” says Dr Zafar Mirza, who was the keynote speaker.

Similarly, the inter-linkages between health and poverty, nutrition, quality education and the sexual and reproductive rights of women cannot be understated.

Goal 17, on fostering partnerships, is perhaps the magic adhesive which will prove to be critical in monitoring and attaining our national health agenda. Currently, there is a dissonance underlining Pakistan’s health economy as 70% of Pakistanis opt for healthcare outside the public sector. Subsequently, the role of public-private partnerships in themselves must be examined and strengthened.

The Parliamentary Taskforce on SDGs, headed by Minister of Information and Broadcasting Maryam Aurangzeb will be decisive in leading the process of creating linkages between provincial policies and action plans, usually developed in silos and rarely backed by financial resources, timelines or strong political will.

Axis of multi-sectoral policy

Apart from improving inter-sectoral linkages, policies and legislative instruments that impact issues of health and scientific progress need to be studied, revamped and created anew if required.

According to panellist Dr Zeba Sathar, Country Director of the Population Council, there is a severe scarcity of targeted policies, in Pakistan. “The three nutrition surveys of 1990, 2001 and 2011 all pointed to under nutrition being a major source of economic burden.” Pakistan has yet to formulate an overarching policy on nutrition.

Malnutrition’s links with food insecurity, compounded by Pakistan’s mushrooming population growth, must also be studied to achieve our healthcare targets. The multiple inequalities prevalent within our provinces cannot be overlooked either.

While addressing the issue of population growth in Pakistan, Dr Sathar stated that “no country with Pakistan’s level of development has such a high population rate.” Unfortunately, other than the Punjab Growth Strategy, no policy created up to date has solely addressed the issue of population growth.

Dr Zafar expanded on the “axis of policy coherence” in which vertical development comprised legislative instruments, and horizontal development required comprehensive, evidence-based policies. Enabling legislation is fundamental to bringing Pakistan’s policies and practices in line with achieving the SDGs for health. For example, a short maternity leave policy can have an adverse effect on the nutrition of a child, and therefore it is critical to study the impact of the underlying legislation and ancillary policy.

Data & awareness

According to Dr Zulfiqar Bhutta, the “intergenerational cycle of ill health, stunted growth and gender differentials in opportunities are a huge stumbling block to progress,” and therefore, “optimising maternal and child health is critical for the development of Pakistan.” These words can only be put to practice if we witness a societal change fuelled by evidence-based data and research, so fundamental to achieving mutual accountability. The long-awaited census will hopefully provide us with some elementary data.

For a country that spends the second lowest per capita on health in the region, things need to change. It is critical that we invest in science at the grassroots level, as the backbone of national development extends beyond roads and bridges.

According to Tim Evans, the Senior Director of Health, Nutrition and Population at the World Bank, “we cannot assume that everyone appreciates the case for health.” He added that “articulating the intrinsic value of health” is therefore a necessary exercise.

Maryam Aurangzeb spoke at length about the government’s role in raising awareness on the SDG health agenda. According to her, a slot will be provided on Radio Pakistan, and PTV, dedicated solely to mainstreaming the sustainable development goals on health. Both the public and private media channels, have the opportunity of playing a huge role in spreading awareness on numerous health and nutrition issues plaguing our country.

Outcomes

The outcome of the workshop was the creation of an independent consortium which would assist and monitor the government’s performance at the federal and provincial levels. The consortium comprising members from the health and science community would also produce an annual report on selected health indicators.

On the face of it, Pakistan has shown leadership in making structural arrangements to further the SDG3 agenda. A Parliamentary Taskforce on the SDGs of national and provincial parliamentarians has been created. Pakistan has also aligned its National Vision 2016-2025 which addresses health, nutrition challenges of the mother and child in accordance with the SDGs.

“Health is not an abstract slogan but a fundamental right,” says Dr Zafar, and now the official policy has been endorsed worldwide. Whilst the expiration of the Millennium Development Goal targets was met with disappointment results for Pakistan, one hopes that we are able to learn our lessons for the future.

** Editor's note: This article has been updated online with a few corrections and images.

The writer is a lawyer. She works at the Public Interest Law Association of Pakistan (Pilap) as their legal counsel. She can be reached at noorzafar7@gmail.com