There was a time when the only news coming out of Balochistan was bullet-riddled. More and more, though, we are seeing a shift in focus because of the massive push for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. CPEC has changed the story on Balochistan, with Gwadar emerging as a main character. This story is pegged to the narrative on violence, but even that is changing in tandem.

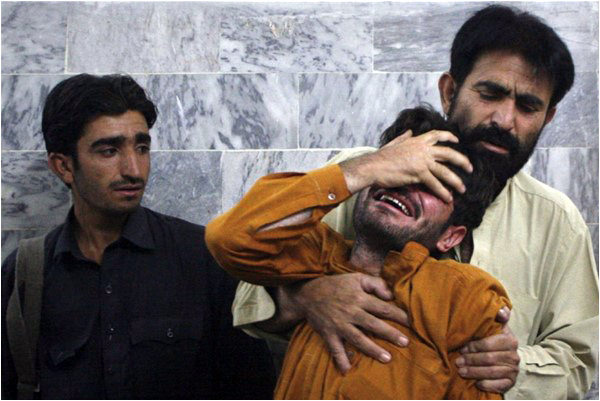

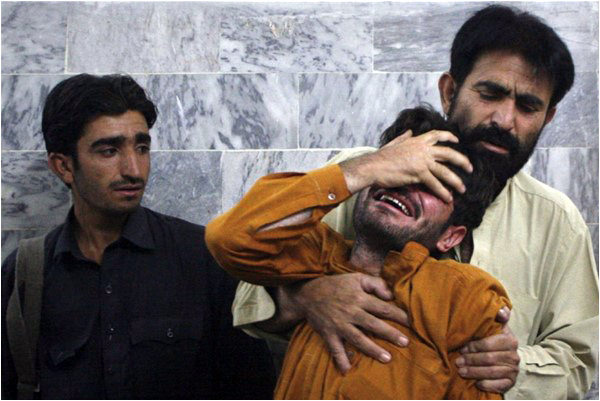

It was, thus, disheartening to see reports of violence in the last few weeks. On May 12, a suicide bomber tried to kill Maulana Ghafoor Haideri, the deputy leader of the Senate, leaving 25 people dead and dozens wounded. On May 13, 10 labourers were killed in a town near Gwadar. On May 19, three more labourers were killed, this time in Turbat. On May 24, two Chinese language teachers were abducted in Quetta. On May 27, a man was killed in mortar shelling from the Iranian side of the border in Panjgur.

Responsibility for these attacks have been taken by banned Baloch nationalist outfits and ISIS through its Amaq news agency. Balochistan’s chief minister, Sanaullah Zehri, declared at a press conference on May 17 that this was the work of “enemies” who were panicked about the progress being made under CPEC.

The labourers were working on infrastructure and the Chinese nationals were language teachers, and so these incidents were linked to CPEC. The attack on Haideri, however, is being taken as the work of ISIS/Daish which has been subletting its violence through local outfits. One theory is that the banned Jaish-ul Islam was behind the assassination attempt by hiring men who were previously associated with al-Qaeda and had been now recruited by ISIS.

When asked if he thought Daish could target him, Maulana Ghafoor Haideri told The Friday Times that his party, the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam had been condemning terrorism in all its forms. “We also criticise the association of [foreign troublemakers] with terror outfits in Balochistan,” he said. “That may well be the reason for the suicide attack on me.” He added that he was not satisfied with the investigation. “I want [...] concrete and correct information. Maulana Fazlur Rehman was attacked in the past. We still don’t know the perpetrators behind that attack.”

Balochistan Home Minister Sarfaraz Bugti categorically denied the presence of Daish in the province in 2016. “We will not surrender to the forces of militancy,” he said after the recent attacks. He added that Balochistan was changing after years of violence and he gave full credit to the law-enforcement and intelligence agencies for containing it. Bugti asserted that remnants of terror outfits were desperately trying to make their presence felt. The sporadic incidents of violence should not be misunderstood as a new wave of terror, he stressed.

Usually, crime statistics shed light. But here, the numbers are difficult to interpret as are the explanations for them. According to the Balochistan home department, the number of incidents of violence has gone down in Balochistan but the casualties have gone up. It says that in 2016, 238 people (including security forces) were killed and 517 were injured in 183 incidents. A year earlier, in 2015, 202 people were killed and 310 were injured in 226 incidents. The home department also says that there was a 95% drop in targeted and sectarian attacks from 44 in 2015 to six in 2016. The number of bombings went down from 162 in 2015 to 128 in 2016. (These numbers could not be independently verified).

Government officials attribute these numbers to targeted action against militants and a general amnesty, which allowed militants to surrender with impunity. “At least 485 militants from the Marri and Bugti tribes have surrendered in recent months,” Balochistan government spokesperson Anwar-ul Haq Kakar told TFT. “The people of Balochistan are fed up with violence. They know the real face of the militants.” He added that the chief minister has been pursuing a policy approved by lawmakers to bring peace and stability to the region.

Spokesman Kakar said that they believe that the situation is returning to normal in the Marri and Bugti areas faster than in Mashkay and Makran. “In Mashkay, where rebel commanders Dr. Allah Nazar and Akhtar Nadeem were already losing ground, many armed militants laid down their arms once news of Nazar’s death broke,” he said. “They have since regrouped, however, and that is why there is still trouble in Mashkay and Awaran.”

This view has been challenged by Sher Mohammad Bugti, a spokesperson for the Baloch Republican Party. “It’s true that a small number of militants returned home to two villages in Sui in the Bugti Tribal Territory after losing family members during the operation,” he said. “But this is nowhere near the numbers being reported by government officials. The media is still not allowed into Dera Bugti to independently report on what is happening.”

It cannot be denied that the people of Balochistan are weary of violence. “There used to be target killings every other day,” said Ahmed Shah, a shopkeeper of Quetta’s Sariab Road. “Not anymore. It’s not because we have a competent government. It is due to the active presence of our security forces.”

Baloch separatists say, however, that the numbers are low because of a dearth of independent reporting. Balochistan’s regional media struggles and mainstream media outlets consider this terrain too risky for its reporters. (According to the Balochistan Union of Journalists more than 40 journalists have been killed in the line of duty since 2005. Not all the deaths were the result of targeted attacks. Some journalists were killed in bombings, while others were caught in crossfire.) Mainstream reporters are mostly based in Quetta and are far removed from what may be happening in Makran, Mashkay or Gwadar. It is often a case of economics when it comes to covering the vast province. “A person with good skills would never work in the media since it is the least paid profession in Balochistan,” one Quetta-based journalist said.

Attacks in 2017

May 13: The banned BLA kills 10 labourers.

May 12: ISIS claims an assassination attempt on Maulana Ghafoor Haideri in Mastung; 25 killed.

May 5: Fourteen people are killed in an Afghanistan-Pakistan border clash.

April 24: The banned BRA claims responsibility for killing four FC personnel in a roadside blast in Kech.

Feb 17: The banned BLF claims a bomb attack that kills three servicemen in Awaran.

Feb 13: Two bomb disposal squad members killed by an IED on Sariab road.

Jan 7: The first sectarian attack takes place. The banned Lashkar-e-Jhangvi Al-Alami says it fired at a taxi cab with five Hazara Shias who were injured on Spiny Road.

This is one reason why it is difficult to get a sense of what is happening. The different explanations from stakeholders clash and independent verification is fraught. Take the topic of missing persons. According to one member of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, Balochistan chapter, relatives of missing persons have stopped registering cases with the HRCP. “It’s been two years now since we have received a formal missing persons complaint,” this person said. “We do hear of missing persons, but nobody wants to register these cases any more. They don’t see the point in risking people’s lives.” Spokesperson Anwar-ul Haq Kakar said, however, that barely 50 missing persons reports have been registered with the United Nations Committee of Enforced Disappearances.

On one front, though, it is undeniable that there has been a change. The sectarian violence in Balochistan has nosedived from 239 deaths in 2013 to 60 in 2016. Five months into 2017, it is just six—although even this is unacceptable. Primarily, the sectarian violence was perpetrated by the anti-Shia Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) that lured Baloch militants into alliances. That created two deadly outfits: Jaish-ul-Islam and the Khalid bin Walid Force. The LeJ has claimed responsibility for almost all the attacks on Hazara Shias in Balochistan. Government spokesman Kakar attributes the decline in sectarian violence since 2014 to the killing in raids of key commanders such as LeJ Balochistan chief Usman Saifullah Kurd and Nasir Mehmood Rind. “Security forces have eliminated their organizational capacity,” he told TFT. “This explains why there have been no mass killings in the Hazara community during the past two years.”

Indeed, it appears that the years of work by the security and intelligence agencies to neutralize terror and sectarian outfits may have borne fruit. Scores of operatives of proscribed outfits were either killed or captured and many are said to have fled to Afghanistan to pledge allegiance to the terror group of their choice.

Two local militants, Farooq Bungalzai and Habibullah Zehri, were controlling LeJ affairs in Balochistan, and were said to report directly to LeJ founder Riaz Basra. With time, major characters, as mentioned by Kakar above, such as LeJ Balochistan chief Usman Saifullah Kurd, Habibur Rehman Rind, Abdul Sattar Karbalai and Ziaul Haq Shinwari were killed in what was counted as a major success by the security forces. The worry is, though, that in some instances they may have been replaced by their immediate juniors.

The collusion of sectarian outfits with sub-nationalists gave birth to several smaller but lethal outfits. One of them was later identified as the Pehlwan Group. Last year, the security forces managed to kill its key operatives, including Haq Nawaz, Zahid Rehman, Amanullah and Abid.

The tide might be turning. In Kakar’s opinion in many areas of Balochistan the killing of people suspected of being government informers has led to a deep hatred of the separatists. “There is a need for more rational voices like BNP leader Sardar Akhtar Mengal,” he said. “He is in favour of gaining rights to resources but within the framework of Pakistan’s constitution. I believe that the concerns of the Baloch people are legitimate, but rather than resorting to violence there needs to be a powerful constitutional fight. Picking up arms is pointless.”

It was, thus, disheartening to see reports of violence in the last few weeks. On May 12, a suicide bomber tried to kill Maulana Ghafoor Haideri, the deputy leader of the Senate, leaving 25 people dead and dozens wounded. On May 13, 10 labourers were killed in a town near Gwadar. On May 19, three more labourers were killed, this time in Turbat. On May 24, two Chinese language teachers were abducted in Quetta. On May 27, a man was killed in mortar shelling from the Iranian side of the border in Panjgur.

Responsibility for these attacks have been taken by banned Baloch nationalist outfits and ISIS through its Amaq news agency. Balochistan’s chief minister, Sanaullah Zehri, declared at a press conference on May 17 that this was the work of “enemies” who were panicked about the progress being made under CPEC.

"At least 485 militants from the Marri and Bugti tribes have surrendered in recent months," Balochistan government spokesperson Anwar-ul Haq Kakar told TFT. "The people of Balochistan are fed up with violence"

The labourers were working on infrastructure and the Chinese nationals were language teachers, and so these incidents were linked to CPEC. The attack on Haideri, however, is being taken as the work of ISIS/Daish which has been subletting its violence through local outfits. One theory is that the banned Jaish-ul Islam was behind the assassination attempt by hiring men who were previously associated with al-Qaeda and had been now recruited by ISIS.

When asked if he thought Daish could target him, Maulana Ghafoor Haideri told The Friday Times that his party, the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam had been condemning terrorism in all its forms. “We also criticise the association of [foreign troublemakers] with terror outfits in Balochistan,” he said. “That may well be the reason for the suicide attack on me.” He added that he was not satisfied with the investigation. “I want [...] concrete and correct information. Maulana Fazlur Rehman was attacked in the past. We still don’t know the perpetrators behind that attack.”

Balochistan Home Minister Sarfaraz Bugti categorically denied the presence of Daish in the province in 2016. “We will not surrender to the forces of militancy,” he said after the recent attacks. He added that Balochistan was changing after years of violence and he gave full credit to the law-enforcement and intelligence agencies for containing it. Bugti asserted that remnants of terror outfits were desperately trying to make their presence felt. The sporadic incidents of violence should not be misunderstood as a new wave of terror, he stressed.

Usually, crime statistics shed light. But here, the numbers are difficult to interpret as are the explanations for them. According to the Balochistan home department, the number of incidents of violence has gone down in Balochistan but the casualties have gone up. It says that in 2016, 238 people (including security forces) were killed and 517 were injured in 183 incidents. A year earlier, in 2015, 202 people were killed and 310 were injured in 226 incidents. The home department also says that there was a 95% drop in targeted and sectarian attacks from 44 in 2015 to six in 2016. The number of bombings went down from 162 in 2015 to 128 in 2016. (These numbers could not be independently verified).

"The situation has improved a lot. No doubt about it. You may call it negative peace or an uneasy calmness. Often, people criticise the militarization of Balochistan. However, this is one of the reasons people are safe," said Saleem Shahid, a journalist in Quetta

Government officials attribute these numbers to targeted action against militants and a general amnesty, which allowed militants to surrender with impunity. “At least 485 militants from the Marri and Bugti tribes have surrendered in recent months,” Balochistan government spokesperson Anwar-ul Haq Kakar told TFT. “The people of Balochistan are fed up with violence. They know the real face of the militants.” He added that the chief minister has been pursuing a policy approved by lawmakers to bring peace and stability to the region.

Spokesman Kakar said that they believe that the situation is returning to normal in the Marri and Bugti areas faster than in Mashkay and Makran. “In Mashkay, where rebel commanders Dr. Allah Nazar and Akhtar Nadeem were already losing ground, many armed militants laid down their arms once news of Nazar’s death broke,” he said. “They have since regrouped, however, and that is why there is still trouble in Mashkay and Awaran.”

This view has been challenged by Sher Mohammad Bugti, a spokesperson for the Baloch Republican Party. “It’s true that a small number of militants returned home to two villages in Sui in the Bugti Tribal Territory after losing family members during the operation,” he said. “But this is nowhere near the numbers being reported by government officials. The media is still not allowed into Dera Bugti to independently report on what is happening.”

It cannot be denied that the people of Balochistan are weary of violence. “There used to be target killings every other day,” said Ahmed Shah, a shopkeeper of Quetta’s Sariab Road. “Not anymore. It’s not because we have a competent government. It is due to the active presence of our security forces.”

Baloch separatists say, however, that the numbers are low because of a dearth of independent reporting. Balochistan’s regional media struggles and mainstream media outlets consider this terrain too risky for its reporters. (According to the Balochistan Union of Journalists more than 40 journalists have been killed in the line of duty since 2005. Not all the deaths were the result of targeted attacks. Some journalists were killed in bombings, while others were caught in crossfire.) Mainstream reporters are mostly based in Quetta and are far removed from what may be happening in Makran, Mashkay or Gwadar. It is often a case of economics when it comes to covering the vast province. “A person with good skills would never work in the media since it is the least paid profession in Balochistan,” one Quetta-based journalist said.

Attacks in 2017

May 13: The banned BLA kills 10 labourers.

May 12: ISIS claims an assassination attempt on Maulana Ghafoor Haideri in Mastung; 25 killed.

May 5: Fourteen people are killed in an Afghanistan-Pakistan border clash.

April 24: The banned BRA claims responsibility for killing four FC personnel in a roadside blast in Kech.

Feb 17: The banned BLF claims a bomb attack that kills three servicemen in Awaran.

Feb 13: Two bomb disposal squad members killed by an IED on Sariab road.

Jan 7: The first sectarian attack takes place. The banned Lashkar-e-Jhangvi Al-Alami says it fired at a taxi cab with five Hazara Shias who were injured on Spiny Road.

This is one reason why it is difficult to get a sense of what is happening. The different explanations from stakeholders clash and independent verification is fraught. Take the topic of missing persons. According to one member of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, Balochistan chapter, relatives of missing persons have stopped registering cases with the HRCP. “It’s been two years now since we have received a formal missing persons complaint,” this person said. “We do hear of missing persons, but nobody wants to register these cases any more. They don’t see the point in risking people’s lives.” Spokesperson Anwar-ul Haq Kakar said, however, that barely 50 missing persons reports have been registered with the United Nations Committee of Enforced Disappearances.

On one front, though, it is undeniable that there has been a change. The sectarian violence in Balochistan has nosedived from 239 deaths in 2013 to 60 in 2016. Five months into 2017, it is just six—although even this is unacceptable. Primarily, the sectarian violence was perpetrated by the anti-Shia Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) that lured Baloch militants into alliances. That created two deadly outfits: Jaish-ul-Islam and the Khalid bin Walid Force. The LeJ has claimed responsibility for almost all the attacks on Hazara Shias in Balochistan. Government spokesman Kakar attributes the decline in sectarian violence since 2014 to the killing in raids of key commanders such as LeJ Balochistan chief Usman Saifullah Kurd and Nasir Mehmood Rind. “Security forces have eliminated their organizational capacity,” he told TFT. “This explains why there have been no mass killings in the Hazara community during the past two years.”

Indeed, it appears that the years of work by the security and intelligence agencies to neutralize terror and sectarian outfits may have borne fruit. Scores of operatives of proscribed outfits were either killed or captured and many are said to have fled to Afghanistan to pledge allegiance to the terror group of their choice.

Two local militants, Farooq Bungalzai and Habibullah Zehri, were controlling LeJ affairs in Balochistan, and were said to report directly to LeJ founder Riaz Basra. With time, major characters, as mentioned by Kakar above, such as LeJ Balochistan chief Usman Saifullah Kurd, Habibur Rehman Rind, Abdul Sattar Karbalai and Ziaul Haq Shinwari were killed in what was counted as a major success by the security forces. The worry is, though, that in some instances they may have been replaced by their immediate juniors.

The collusion of sectarian outfits with sub-nationalists gave birth to several smaller but lethal outfits. One of them was later identified as the Pehlwan Group. Last year, the security forces managed to kill its key operatives, including Haq Nawaz, Zahid Rehman, Amanullah and Abid.

The tide might be turning. In Kakar’s opinion in many areas of Balochistan the killing of people suspected of being government informers has led to a deep hatred of the separatists. “There is a need for more rational voices like BNP leader Sardar Akhtar Mengal,” he said. “He is in favour of gaining rights to resources but within the framework of Pakistan’s constitution. I believe that the concerns of the Baloch people are legitimate, but rather than resorting to violence there needs to be a powerful constitutional fight. Picking up arms is pointless.”