When the idea of this article took shape, it was only meant to describe this author’s childhood reminiscences of offering prayers in the 1960s at the Badshahi Mosque Lahore. However, it soon became evident that no matter how disciplined the author stayed, he would meander through the by-lanes of memory and history, much like the river to the north and west of the city. Eventually, this article has ventured into unpredictable directions.

This author was born in Gowalmandi and raised within the Walled City. His love of the city, its bazaars, mohallas, kochas and, above all, its people, has already resulted in many articles about the city and his initial years of life spent there. The current effort, too, would add to this anthology – with five to six articles; each depicting a different aspect of the city.

Among my earliest delightful childhood memories are of going to the Alamgiri Mosque, popularly known as the Badshahi Mosque to us, the inhabitants of the Walled City of Lahore, to offer the Eid prayers with my family. This memory, however, needs some explaining.

My parents were migrants from Amritsar in the 1947 partition. Having wandered through a few cities, they finally made Lahore their home, where a large part of their families, too, had settled. They found living space in a barsati on the top floor of a four-storey high building in the walled city. A barsati was a well-ventilated room on the roof and was used during the breezy monsoon season when extreme humidity made the closed rooms on lower floors unbearably sweltering. Of course, that was the era when there were no air conditioners and the supply of electricity was scarce and uncertain to run the fans. The building was originally built as the family home of a prosperous goldsmith in the early 1940s. It stood on an approximately 160 square yard block of land at the end of the street, right opposite to the main gate of the Lahore Water Works; more commonly called the Paniwala Talab. The building has now been rebuilt as a commercial centre for small cottage industry units.

Back in the 1960s, on Eid days and the last Fridays of Ramzan (Jumatul-Wida), dressed in our penurious best, my father, his younger brother and maternal cousins, accompanied by their kids, would walk out of our street to attend prayers at the Badshahi Mosque. Although there were some other mosques in the area and en route, most people in our locality preferred going to the great mosque for collective prayers. Exiting our narrow street, we would turn left on the road in front of the main gate of the Talab (Water works) and join the stream of people flowing towards the mosque. This road is called the Pani Wala Talab Road at this point, and continues as Kali Beri Bazaar till past the Kareem Bakhsh Mosque and the Nau-Gaza shrine (nine yard long sarcophagus) further ahead on the right. From the Barood Khana Road (the ammunition depot road) exit on the right, the road ahead, till the Tibbi Bazaar opening on the left, is called Heera Mandi Bazaar.

We would approach the tri-road Heera Mandi Chowk where, on the left, the now famous Phajja Siri Paye (a famous dish of goat trotters) and Arif Chatkhara (spicy and tangy snacks) do a brisk business. Here, we would turn right on the Shahi Mohalla Street with the twin streets named Uncha and Neecha Cheet Ram on the left. Both these streets have separate openings on this road but merge on western end near Taxali Gate, where the famous progressive poet Ustad Daman used to reside in those days. Going past Taj Mahal Sweets on the left, our favourite outlet for a luxurious Lahori breakfast, and crossing the Fort Road, we would enter the Fort-Mosque-Gurudwara-Baradari complex through the Roshnai Gate (Gate of Lights).

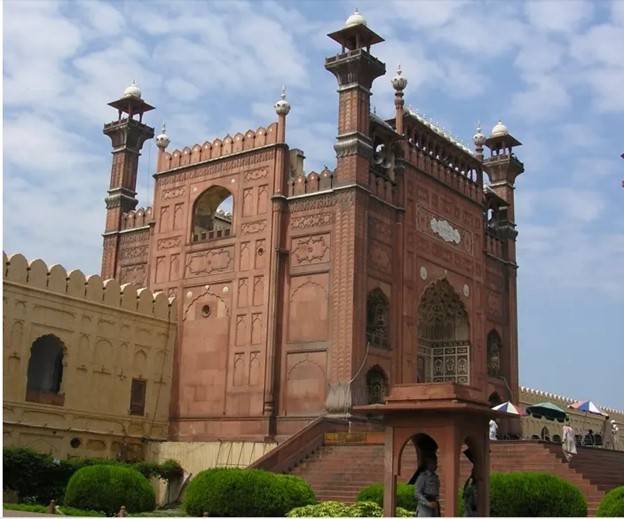

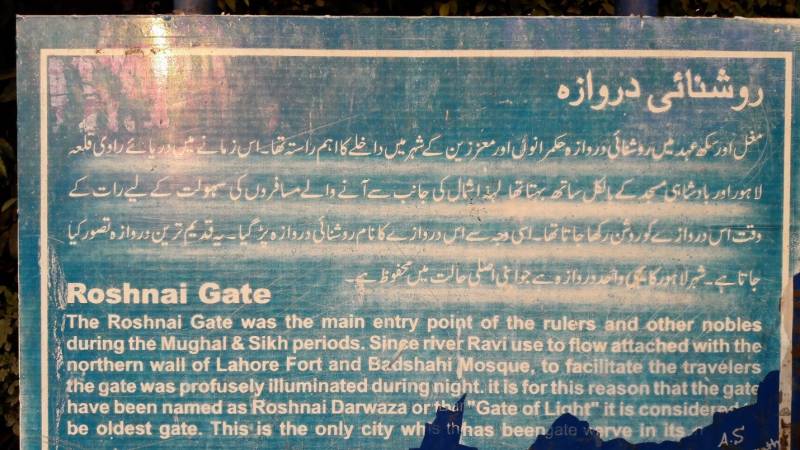

Roshnai Gate, as per the information displayed on a signboard on its side, is the only gate of Lahore that is in its original state. It is a large gate capable of accommodating an elephant to pass through. It has a smaller inbuilt gate for pedestrians. Normally, only the smaller gate remains open, whereas the bigger gate is used for larger crowds during the Eid and Jumatul-Wada prayers. The gate is thus named because it was the only city-gate that was well lighted at night during the Mughal era. Now those lights are no more but the adjacent food street, with brightly painted houses, is well lit and remains busy from early evening till late night.

On our return walk, we would stop at the Taj Mahal Sweets to buy our Eid breakfast of puri, channay, halwa, qat’lummas, qeemay-wali tikki and sweet puris

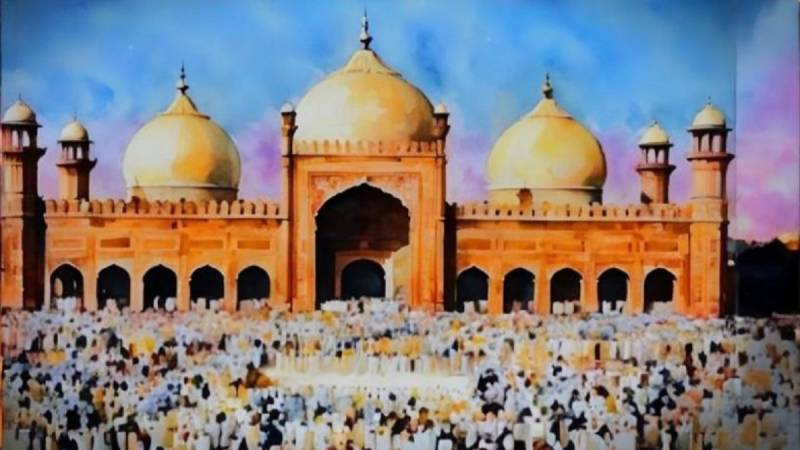

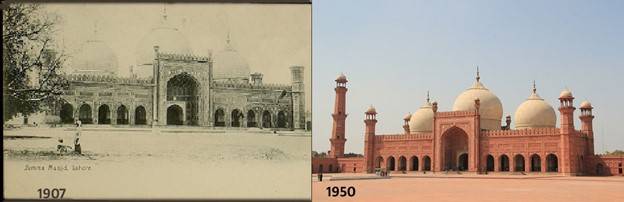

The mosque lies on the far left, as seen from the Roshnai Gate entry point. In its red sandstone and marble construction with its majestic gate elevated above the surroundings, it inspires reverential awe. It has prodigious measurements. The massive gateway is 67 feet wide, 63 feet deep and 65 feet high, including the small upper domes. Its three-sided staircase has 22 steps. The twin level courtyard of the mosque is a 528-feet-sided square. The water tank in its middle is a 50-feet-sided square and three feet deep.

The main prayer chamber is 276 feet long, 84 feet wide and 50 feet high. The four massive corner minars, 67 feet in circumference at the bottom and 176 feet in height, are built in four stages and have a self-contained staircase of 204 steps in their centre. They used to be open for the public to climb up to the second gallery, and this author has gone up there a few times. It provided a good view of the surroundings. The central 49-feet-high dome is 65 feet in diameter at the bottom, bulging to 70 feet in the centre. The side domes are 52 feet in diameter at bottom, bulging to 54 feet with height of 32 ft. The side aisles around the central courtyard are 80 in number and were used for housing live-in students. The mosque has a capacity for one hundred thousand worshippers. As is evident from these figures, the entire structure is huge by any standards.

Between the gateway and the right compound wall is the grave of Sir Sikander Hayat Khan, the Premier of Punjab (1937-42), who died in office and was responsible for extensive renovation of the mosque. On the left side is the more elaborate mausoleum of the national poet Sir Muhammad Iqbal. Here, on the road below the gateway, the Khaksars (the short-lived party founded by Allama Inayat Mashriqui) used to parade in those days after the prayers, with their spades on their shoulders like soldiers holding guns. I haven’t seen the Khaksars in a long time.

As one enters the mosque, on the immediate right side is the depository of some sacred relics on the first floor. This depository has unfortunately been turned by the mosque staff into a source of collecting money from the visitors. In my last visit, I found that a member of the staff at the entrance urged the visitors to go up the stairs and his other companions inside exhorted them to donate money. This undocumented and unaccounted money, running into millions by my estimate, goes into the pockets of the staff. The Punjab government needs to control this demeaning practice. The mosque Khatib, now the chairman of Ruet-e-Hilal committee, holds a prestigious position in Lahore society and is responsible for protecting the sanctity of the mosque.

We would climb the steps on to the broad platform before the entrance, take off our shoes and tuck them under our arms. We would walk through the porch of the gateway as the courtyard opened up in front. We never prayed in the main prayer chamber at the head of the mosque on these special occasions. For one, it was only the early birds who could find space in there. Second, some space behind the Imam was reserved for either the chief minister or the governor, or both, and their staff, who used to, and continue to, offer their prayers here. Third, it was more fun sitting in the vast courtyard. We would spread the bed sheets that we brought with us to sit and pray on. The elders stayed on each end of the line and ensured that the younger children stayed in the middle so that they couldn’t wander off.

During summers, it can be extremely hot and humid. Sitting in the open sun, even in the early hours of the day, is very uncomfortable. It is understandable that pegging tents can damage the marble floor. I hope that some sound engineering solution can be found to provide cover in the courtyard during the hot months. However, providing pedestal fans or desert-coolers should not pose any difficulty. During winters and moderate weather however, it was a pleasure praying in the courtyard.

There used to be a lot many observers on the roof adjacent to the main entrance; that is, behind the prayer lines. They included PTV cameramen, journalists and reporters. Many foreigners also came to witness the grand spectacle of tens of thousands offering collective prayers. Most children would remain standing near their elders, and took a keen look at the large crowd.

At the end of the prayers, everyone got up to warmly embrace everyone else. We would fold our bed sheets and gather in a tight circle to undertake the return walk. As the entire assembly in the courtyard had only one exit to use, the mammoth crowd exiting this gate could easily cause a stampede. As we used to walk out of the courtyard, our father would stay behind us to slow the people in the rear, and thus to avoid the suffocating jam. It was an exhilarating – though somewhat claustrophobic – experience to be in the midst of an overbearing crowd who continuously recited prayers loudly. I still don’t understand why we had to get into that dangerous crowd instead of waiting for the rush to be over.

On our return walk, we would stop at the Taj Mahal to buy our Eid breakfast of puri, channay, halwa, qat’lummas, Qeemay-wali tikki and sweet puris. The restaurant was invariably crowded at this time. The trays of stuff arriving from a separate frying area would be empty before they reached the shop. Everyone had to snatch whatever one could. People would then calculate the money they owed to the shop and literally throw it over the heads of the crowd towards the shop owner. This description may be a little bit of exaggeration, but it is not far from the truth.

Besides the breakfast, we also bought toys, some of which produced loud annoying sounds all day, but which thrilled the kids no end.

The Mosque and the Fort define the city of Lahore. People still take delight in going there to pray, hold their nikah ceremonies or simply visit with their families. A trip to the complex, together with to the Greater Iqbal Park, can take a whole day. It entails long walks and is quite tiring. However, the visit is exhilarating and this author always comes back with a sense of belonging and pride.

The next article in this series will describe the surroundings of the mosque.