Punjabi MPAs

Sir,

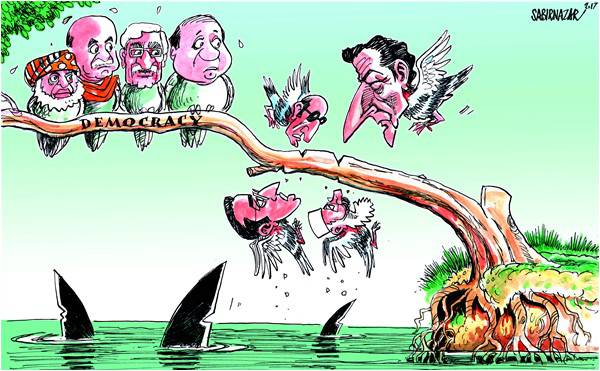

World Punjabi Congress Chairman Fakhar Zaman has written a letter to members of the Punjab Provincial assembly emphasizing the adoption of Punjabi language as the language of the house. He stated that during the last government of Punjab, the then Chief Minister Chaudhry Pervaiz Illahi passed the rule that MPAs are allowed to speak in Punjabi but unfortunately, the MPAs because of their inferiority complex and being illiterate in the context of the history of Punjab, Punjabi language and Punjabi culture desisted shamelessly from speaking in their mother tongue. The WPC Chairman has further stated in his letter that according to UNESCO statistics Punjabi language is the tenth largest spoken language in the world but it is a sad story that the Government of Punjab is oblivious to declaring Punjabi as medium of instruction at the primary level. The Chief Minister keeps on shouting to the treetops about Punjab but perception of Punjab lamentably is shorn of Punjabi language and Punjab culture ethos. Flyovers, underpasses, the Metro and Orange train may have their own utility, but the identity of the Punjab lies in the Punjabi language which has a great Sufi heritage. It emphasizes a culture of tolerance, brotherhood and mutual love which is presently needed for fostering better relations between Punjab and other provinces.

Zaman has categorically mentioned that Punjabi politicians, bureaucracy and the Punjabi elite are the biggest enemy of this great language. Fakhar has sought both moral assistance and the official help to prevail upon the recalcitrant attitude of the Punjab Government. He brought it to the notice of assembly members that UNESCO has recently come up with a disturbing report that this language will become extinct within next thirty years. In my opinion, Fakhar said, this language of Waris Shah and Bulleh Shah can never slip into extinction if our intellectuals, writers, folk artists and the people’s representatives pledge to safeguard its future by adopting it at all educational and legislative levels. He further said that some radical changes are required in the curricula of Punjabi language from matric to Masters level, as it is purely reactionary and reminiscent of Zia Ul Haq’s martial law period. He appealed to members to call upon the the chairman of the HEC in Punjab and vice chancellor of Punjab University to bring about major changes in the textbooks which are prepared by inefficient retrogressive Urdu and Punjabi writers and scholars. Fakhar said that he is in favour of teaching Urdu and English after the primary level because Urdu is lingua franca and English is practically our official language and also the tongue of the global internet.

The WPC chairman reminded the MPAs that there is no place in Punjabi and Punjab’s domain for chauvinism and jingoism. He branded the puerile slogan “Teri Pug nu laga dagh – Jag Punjabi Jag” as a mindless slogan which was designed to impose hegemony over smaller provinces. Zaman said that WPC plans to launch peaceful demonstrations in front of the Punjab Assembly and also take legal recourse for the declaration of Punjabi language as the medium of instruction. Addressing the MPAs he said that they are the representative of the people of Punjab, who by and large speak Punjabi and members would be betraying them by maintaining criminal silence against the promotion of their language. Concluding his letter, Zaman stated that ten thousand MA Punjabi degree holders are unemployed, the Waris Shah’s Mazar is in a bad shape and many Punjabi relics are at the verge of desecration. He said there is a need to establish the first ever Punjabi University in Lahore, allocate more funds to the organizations working for the promotion of Punjabi language and culture and for the advertisement to Punjabi dailies be increased to the equivalent of those given to Urdu dailies. He has urged the MPAs to educate themselves on their history, culture, the Kissan movements, Sufi traditions and heroic movements by reading his latest book in Urdu, partly English, titled “Punjab, Punjabi and Punjabiyat”. He said that if you are a son of the soil, you should speak in your mother tongue otherwise you will be letting down the land of the five rivers.

Zaki Shah,

Via email.

Nuclear modernization

Sir,

The nuclear race in South Asia is intensifying, thanks, amply to New Delhi’s fear that its military is starting to lag behind China’s. Another point to ponder is: For India, is deterrence the only true purpose of nuclear weapons?

Over the past decade, the South Asian region has become alarmed by the Indian ability to wage conventional war and its ambitious nuclear weapons are also a threat for peace. India’s gigantic military expenditure has taken an asymmetric approach in building up its nuclear arsenal.

On September 2009, the Financial Times reported a story titled, “India raises nuclear stakes” saying that India can now build nuclear weapons with the same destructive power as those in the arsenals of the world’s major nuclear powers, according to New Delhi’s senior atomic officials.

A recent shows Indian heavy reliance on nuclear weapons with an increased estimation program in the near future. Some newspapers also published this report with a label of China being the sole reason for such development. However, Zachary Keckonce argued that India’s nuclear development was just a mistake to be remembered because it has not served the purpose of what India has aimed for (deterring China), since China only enacts low intensity attacks along their shared border.

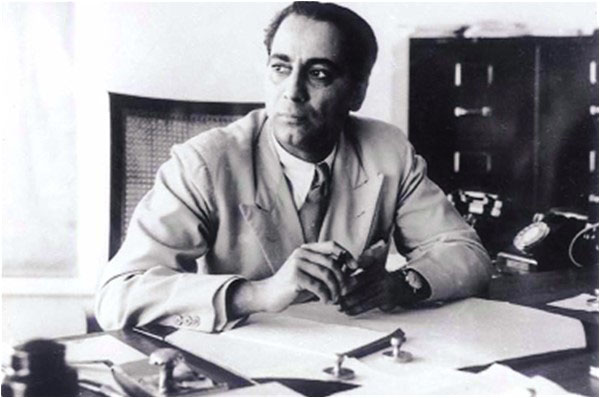

The history of nuclear program of South Asia is devastating. In his book The Genesis of South Asian Nuclear Deterrence: Pakistan’s Perspective, Brig. Naeem Salik traces the origin of India’s nuclear programme and the aspects of its nuclear double standards. He provides a comparative study of the dynamics of the South Asian nuclearization which concludes that Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and father of the Indian bomb, Dr. Homi Bhabha, recognized the dual nature of nuclear technology, and believed it could be beneficial for India.

The further depressing aspect of this story is that India’s nuclear programme is moving forward steadily, without any hindrance from great powers. It secretly pursued nuclear weapons, which it declared in the late 1990s. The international community engaged with New Delhi, constantly extending a hand of friendship, exemplified by different diplomatic measures such as the Indo-US nuclear deal.

In order to mainstream Fast Breeder Reactor, DAE gears up to commission a nuclear reactor at Kalpakkam. But the safety inadequacies of India’s FBTR still need to be questioned. This rock ’n’ roll approach of India guarding its vested nuclear interests cautions that international community, shaking hands with India through nuclear diplomacy, probably does not know everything India has done to protect its obsessive nuclear secrecy.

That being said, New Delhi continues to sign nuclear deals (16 in number until present) without being hindered by any of the so-called nuclear non-proliferation purists. Despite not signing the Non-Proliferation Treaty, India has also assigned the uranium deal with Australia which has raised various important questions regarding the use of Australian uranium in India. As of 2016, India has signed civil nuclear agreements with 16 countries which include; Argentina, Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, France, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Namibia, Russia, South Korea, the United Kingdom, the United States and Vietnam. Has India succeeded enough to bury her proliferation record over decades and shove it under the carpet? It is a lethal hoax.

Under these circumstances, it’s also astonishing how it was even a possibility to grant India, the membership of Nuclear Supply Group, which is a creation of its own disconcerting pursuit of nuclear weapons. Interestingly, India has been building its case for international recognition as a (normal) nuclear weapon state for years, seeking admission to the Group, where, permitting an NPT-outlier like India will create the domino effect, when it will become a compulsion for states like Pakistan to opt for strategies commanded by their security concerns. Meanwhile, on the other hand, it was also revealed that India has been busy developing a secret nuclear city. So it is important for NSG to abide by the criteria established by their own policies and must consider that its decision will also affect strategic stability in the region of South Asia.

When all’s said and done, India’s decision to rely on nuclear weapons as a means of warding off an attack from a more powerful neighbour has increased the chance of nuclear warfare breaking out in South Asia. The Indian pursuit for increased nuclear deterrence is hardly startling, it is an obvious example of an alarming pattern of pretense nuclear powers in the region, having a long and volatile history of hostility toward each other.

Lastly, more of an Indian aggressive nuclear posture has supplemented the already tense conditions of stability in South Asia.

Usman Ali Khan,

M.Phil candidate,

Quaid-e-Azam University,

Islamabad.

Seraiki SOS

Sir,

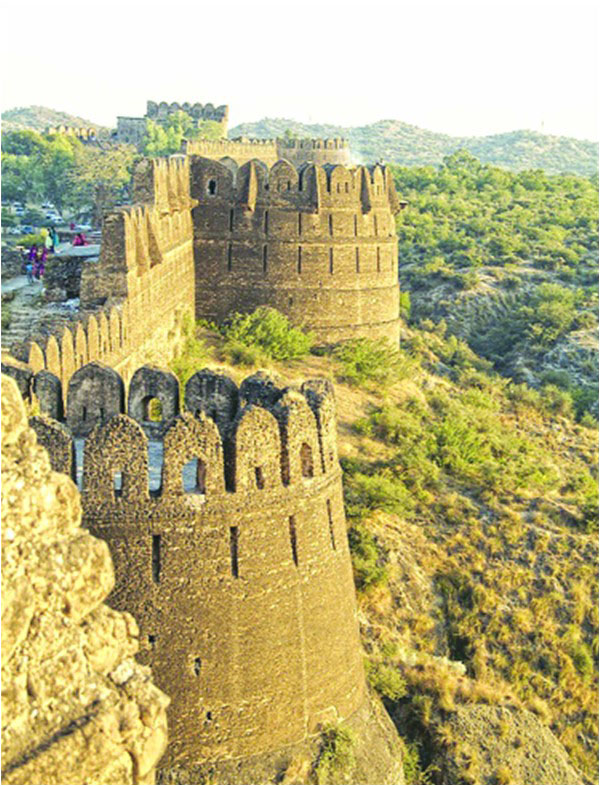

In the July 14, 2017 issue of The Friday Times, Dr Ayesha Siddiqa has brilliantly summed up the various dimensions of the Seraiki question in Pakistan with an analytical mastery that is exclusively her forte. A point that found great resonance with me was that speaking for the Seraiki identity is often interpreted as a treacherous plot against the geographical sanctity of the Punjabi motherland. As a Seraiki boy spending his formative youth in Lahore through much of the early 2000s, I also encountered similar sentiments that I probably lacked the intellectual finesse at the time to respond to effectively. However, even the most cursory reading of history shows that the Punjab in its present cartographical form is not older than exactly 199 years.

Without going into acrimonious detail, four dates are key in this history: 1818, when Ranjit Singh conquered Multan which had hitherto been a separate province/sultanate encompassing the present-day South Punjab through all Muslim dynasties of India; 1849, the year when the British wrested Multan from the Sikhs; 1947, when Sir Cyril Radcliffe drew imaginary lines on outdated maps; and 1955, when the princely state of Bahawalpur was forcibly incorporated into the one-unit of West Pakistan. Therefore, there is no mythical Punjab that extends back into time immemorial. And in the present-day, the democratic paradigm, as tried and tested around the world, favors smaller administrative units so as to discourage regional resentments and exploitation. Yes, the demand for a Seraiki administrative unit is provincial. However, the counter-argument isn’t any less so. Punjabi elites just want the benefits that accrue from a big population.

Linguistically, Seraiki is often relegated to the status of a localized Punjabi dialect. A language, especially in the context of the Indus and Gangetic Plains, is considered to be an umbrella for a number of dialects that may have some differences in structure and elocution but are still largely understandable amongst one another, the numerous dialects of the Hindi of Uttar Pradesh being a case in point. Why is it then that a native Punjabi speaker struggles to understand even the most basic spoken Seraiki much less utter the special sounds of ‘b’, ‘d’ and ‘j’ that Seraiki shares with Sindhi? A Sadiqabad native, however, at the border with Sindh would be easily understood in Bhakkar on the northernmost tip of the Seraiki belt because Bhakkar and Sadiqabad speak different dialects of the same language: Seraiki.

Beyond history and semantics, Seraiki’s greatest misfortunes exist in the cultural realm. Despite being the only language that is indigenous to all four provinces, as Dr Ayesha Siddiqa points out, it is seldom recognized as such. On the contrary, it has come in vogue of late among Baloch nationalists and the “fashionable” Left of the big cities to claim the Dera Ghazi Khan and Rajanpur districts of southern Punjab as part of Greater Balochistan. While it is fact that a majority of the ethnic stock of these districts’ populations is Baloch, it is equally solid fact that Seraiki is the mother-tongue of the vast majority of these Baloch. As Baloch tribes descended from the Koh-e-Suleiman Range between the 14th and 18th centuries to settle in the Indus Plain, they gave up Balochi for Seraiki over the generations. Of the seven great Baloch tribes of Dera Ghazi Khan recognized by the British, i.e. Leghari, Khosa, Gurchani, Drishak, Mazari, Loond and Buzdar, only the Buzdars and the Chiefs of the Mazaris speak Balochi as a mother tongue because they still reside primarily in the mountains. The rest are all Seraiki-speaking and have adopted the ways of plainspeople. In fact, the entire districts of Jafferabad and Naseerabad in Balochistan, and many prominent Baloch tribes in Sindh, e.g. Talpurs, Jatois, Zardaris, Legharis, speak Seraiki as their native tongue. Rural Sindh is fundamentally bi-lingual with many Sindhis fluent in both Sindhi and Seraiki.

Despite such vast geographical spread in Pakistan, lack of recognition for Seraiki at a national level, however, is not entirely incomprehensible. A major portion of the blame lies at home: at the doorstep of the Seraiki feudal, spiritual and political elite. Still apparently in awe of their erstwhile colonial overlords, the Seraiki elites are notorious for living the high-life in Lahore and Karachi while only looking to their native towns and villages for votes and economic extraction. This neglect factors directly into the dismal human development situation in Seraiki areas which have consistently failed to compete with the rest of Punjab in upward social mobility through representation in the state apparatus. As a consequence, and coupled with the disproportionate political and bureaucratic power concentrated in north-central Punjab, even though the millions of Seraikis contribute to Punjab having the lion’s share in civil service quotas and national finance awards, they barely derive any benefits. In addition, there has been a consistent trend among the entrenched elite to undermine any politician attempting to politicize the Seraiki identity. Taj Langah, the late champion of the Seraiki cause, was only elected once to national office, in 1970, when the PPP ticket saw him through. In subsequent elections, he regularly polled in the hundreds.

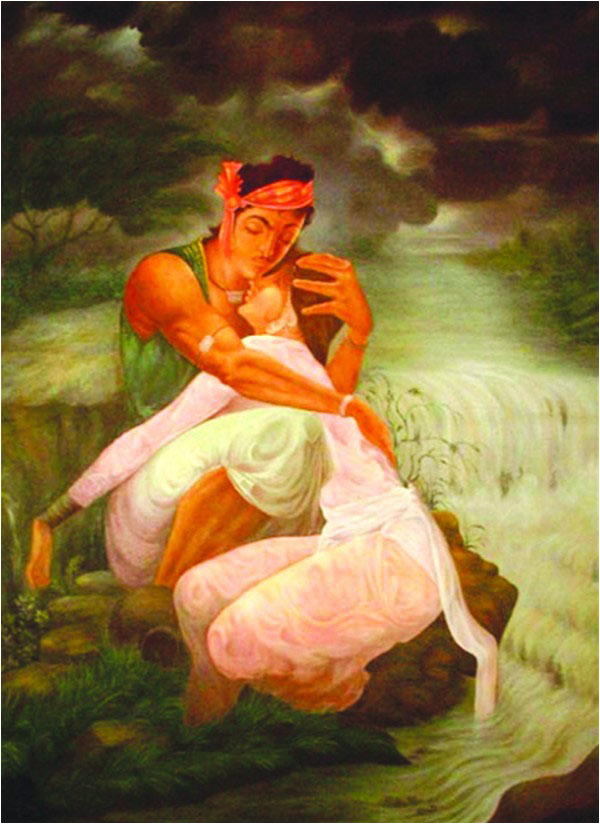

On the matter of language, Pakistan’s, and specifically Punjab’s, inferiority complexes are an open secret. We are keen to teach our children foreign languages as a mark of refinement and class, and we find the tongue of our mothers’ lullabies uncouth and socially unacceptable. The Seraiki elite’s affliction with this mental sickness is exceptionally acute. We hardly own Khwaja Ghulam Farid, the ultimate Seraiki Sufi poet, much less Sultan Bahu of Ahmedpur Sial, whose Abyat-e-Bahu in the Jhangochi dialect of Seraiki are now identified as Punjabi mystical literature. We also don’t care that Heer-Ranjha is not a quintessentially Punjabi folk-tale, but that the language in which Heer and Ranjha swore undying love to each other was closer to Seraiki. And in a few decades, our children probably would not even think twice about a dead language that some people called Seraiki, while others insisted it was just a backward Punjabi dialect.

Hasnain Haider,

Multan.