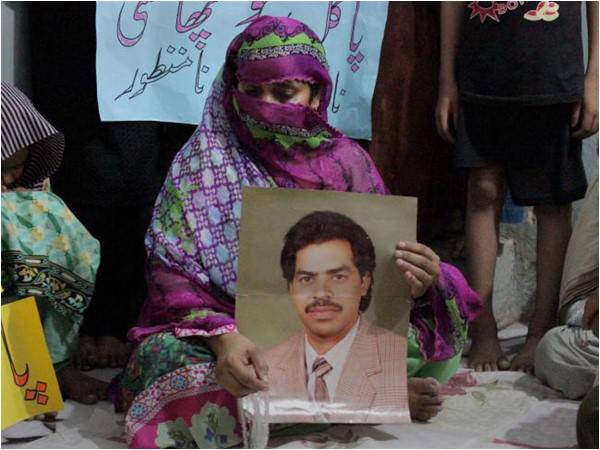

Fifteen years ago, in Vehari, an FIR was registered against a man for murdering an imam. According to the FIR, before opening fire, the man shouted that he had been trying to attain spiritual knowledge from the imam for the past few years but to no avail. That man, Imdad Ali, was convicted and sentenced to death on July 29, 2002.

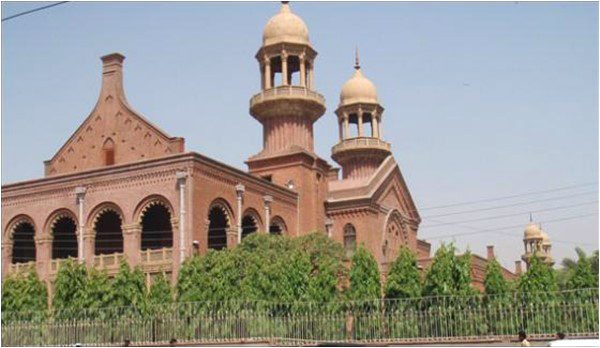

According to the law, no death sentence can be executed unless confirmed by the high court. Imdad Ali’s murder sentence was confirmed by the Multan bench of the Lahore High Court, in 2008. His appeal in the Supreme Court was rejected last year.

For the past 14 years, Ali has been on death row. His mercy petition was rejected by the president, a failed writ petition against his execution was dismissed by the high court this July, and then by the Supreme Court in September. Two days before Imdad Ali was due to be hung, his execution was temporarily stayed by the Supreme Court.

Out of the 14 years Ali has spent on death row, the last three have been spent in solitary confinement. These numbers are staggering even when considered without the fact that Imdad Ali was officially declared a paranoid schizophrenic by the head of psychiatry, Dr Naeemullah Leghari, at Nishtar Hospital in 2012.

“There was history of self-talk, gesturing, posturing, odd ideas and beliefs, bizarre ideations and lack of concern for his death sentence,” Dr Leghari told the Justice Project Pakistan. “During his stay in the ward… [h]is mental state exam was significant for: Lack of self care, incoherent speak (lacking clarity) .... He had bizarre paranoid delusions and also had incongruent grandiose delusions. He had no insight into the illness.” Imdad Ali’s mental status and the fact that he was diagnosed with genetic paranoid schizophrenia did not sway the Supreme Court. Paradoxically, it explicitly rejected schizophrenia as a mental illness.

The year Ali was tried and convicted by the sessions court, 200 miles away, another case was registered in Rahimyar Khan. The case involved the abduction and rape of Salma, the daughter of a man called Ghulam Qadir, and the subsequent murders of Salma, Abdul Qadir, and his son, Akmal. It was suspected to be a case of a family enmity.

In 2005, Out of at least eight people arrested and put on trial, six nominated accused people were released. One of them was handed down a double life imprisonment sentence and the two brothers, Ghulam Qadir and Ghulam Sarwar, were convicted and sentenced to death. The decision was upheld by the Bahawalpur Bench of the Lahore High Court.

On June 10, 2010, the Ghulam brothers filed leave to appeal in the Supreme Court where a two-judge bench only granted leave to re-examine evidence pertaining to Salma. The death sentence remained unchanged for the other two murders. Here onwards, the case’s trajectory take a confusing and terrifying turn.

Six years later, a different SC bench took up the case. Upon revisiting the last SC order and finding inconsistencies in it, they decided that they would exercise their suo moto right to reassess the evidence for all three murders, for the entire case. The honourable judges found glaring, material contradictions in the evidence of the prosecution witnesses and declared that the prosecution had miserably failed to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt. The brothers were free to go.

The news of their acquittal never reached them. After spending the last decade of their lives on death row, both Ghulam Qadir and Ghulam Sarwar were wrongfully executed in October 2015, exactly a year before they were exonerated.

Bottom up: pre-trial investigations & trials

Many questions arise from the major lapses in due process and the lack of application of sound, legal reasoning at all levels. The most uncomfortable questions, however, can be traced to the beginning of both cases, and all criminal cases in general: This is the substandard, unprofessional pre-trial investigation and trial practices you will find in our lower courts.

In Imdad Ali’s case, we have been quick to deconstruct the Supreme Court’s most recent parochial order, which seemingly expels schizophrenia from qualifying as a ‘mental disorder’ according to the definition of the Mental Health Ordinance, 2001, ironically enacted the same year Imdad Ali’s life was incarcerated. Yet, we have failed to examine why his illness was only officially examined and noted by the courts in 2012—10 years too late. The Imdad Ali case encapsulates the indelible nature of evidence recorded at the trial level. If you don’t get it right the one time, your chances of walking out a free man are slim.

At the trial level, not only was the plea of insanity indirectly raised during cross-examination, but Imdad’s own wife testified to his unsound mind. Defence witnesses, let alone women, rarely take the stand in murder trials in Pakistan, so this in itself was significant. Sadly, these were perhaps the only steps that could have been taken by Imdad Ali, since his family could not afford the service of a professional medical expert.

While confirming Imdad’s death sentence, the judge stated the following: “If the learned trial judge himself would have felt that the appellant was not (a) normal person, he could himself [have] take notice of [it].” He was perhaps not aware of the litmus test used to assess the sanity of mentally ill prisoners in our courts: ‘Please state your name’. If the accused answers correctly, he is deemed sane.

Pakistan has a broken criminal justice system. Our top courts are overburdened and under resourced and lower courts are even more so. Add to this the substandard quality of investigations, apathetic and underpaid defence lawyers and a lack of systematized legal aid for poor clients and you have a perfect recipe for disaster.

The case of the two brothers is also illustrative of these shortcomings. Once a crime is allegedly committed by someone, the wheels of our broken criminal justice system come into motion. Someone must be punished. It is a dangerous and sadly common pressure tactic and modus operandi, for the complainants (people who register the case) to cast a wide net and implicate as many people (usually relatives) as possible. The complainants are further emboldened by a penal system and overzealous police officials. The formula is: implicate as many people as possible because at least a few will be convicted and sentenced to death.

If you are implicated for murder, your chances of conviction at the trial stage are staggeringly high. It is perhaps convenient for the lower courts to send cases up to the high courts, passing on the responsibility of sifting through and acquitting dangerous, hardened criminals, juveniles and the mentally ill. Once up, death penalty cases are weeded out at the appellate stage, with most sentences being commuted to life and in some cases, acquittals. But how do we make it up to men and women who have lost decades behind bars?

“There are a number of problems in the system,” remarks defence counsel Asad Jamal. “True, that it’s convenient for judges of lower courts to transfer the burden to the higher fora, but they’re also scared of being labeled ‘corrupt’ or soft. Their training and the system they work in and survive in is based on the idea of subservience and obedience to the higher authority. Their training doesn’t impart them confidence.” An HRCP report substantiates this trend. From December 2014 (when the unofficial moratorium was lifted) to date, 359 people were sentenced to death by sessions courts compared to 107 in the high court.

However, according to Asad, the problem also lies with jurisprudence of the higher courts. “The supreme court’s death penalty jurisprudence is, in more ways than one, based in large part on the assumption that judges can be counted on to apply the law conscientiously and fairly,” he says. “In some cases, the Supreme Court has gone to the extent of saying that establishing motive was not necessary to award the death penalty. This shows how little value our judges attach to human life.”

This sends a strange message to trial judges, who instinctively gravitate towards awarding the death penalty. There is a trickle-down effect of this malaise of ineptitude, the police is lazy, the prosecution is lazy. No one is held accountable. “Therefore, there’s every likelihood that the innocent may go through unjustified imprisonment before they’re acquitted or may be hanged because some of the cases escaped careful scrutiny even at the highest forum,” states Asad Jamal.

Appellate courts will very seldom reevaluate the facts of a case; that is the trial court’s job. Schizophrenic Imdad Ali’s fate was sealed during his trial as all appellate courts thereafter refused to invite any new facts. Had the issue of his state of mind been explored more deeply at the trial level, we would perhaps not be in this bind.

Top-down breakdown

October 2016 will go down as historic in its exposé of the deep-rooted, systemic, gaping flaws in Pakistan’s criminal justice system. An even more troubling certainty is that the apex courts have let us down in equal measure, if not more.

It is absolutely outrageous and unacceptable that two men were made to walk the gallows, only to be exonerated a year later. In a cruel twist of fate, owing to the unavailability of an executioner in Rahim Yar Khan, the brothers were moved to Bahawalpur. The State and its functionaries are trained to only dispense punitive injustices, it seems.

In the case of Imdad Ali, the Supreme Court bench was provided with the chance to deliver an important judgment on mental illness and its association with criminal behaviour. The apex court failed to deliver. Or perhaps there is still a glimmer of hope left.

“In Pakistan, we are not only subject to a criminal justice system that prescribes the death penalty for 27 crimes, but one that is beset with inefficiencies and corruption,” says Maryam Haq, the legal director of Justice Project Pakistan. “This system is unacceptable for so harsh and irreversible a punishment that has already been meted out to 420 people since December 2014.” This macabre record includes juveniles, the mentally ill and innocent people who were tortured into making confessions.

In the Bahawalpur case, the two brothers were acquitted a year after they were hanged, even though they maintained their innocence until the very end. Ghulam Sarwar and Ghulam Qadir were failed by the law, and Imdad Ali came within inches of the noose under the same system. Haq adds, though, that “Unfortunately, neither of the two cases are aberrations.”

The writer is a lawyer. She works at the Public Interest Law Association of Pakistan (PILAP) as their legal counsel. She can be reached at noorzafar7@gmail.com

According to the law, no death sentence can be executed unless confirmed by the high court. Imdad Ali’s murder sentence was confirmed by the Multan bench of the Lahore High Court, in 2008. His appeal in the Supreme Court was rejected last year.

For the past 14 years, Ali has been on death row. His mercy petition was rejected by the president, a failed writ petition against his execution was dismissed by the high court this July, and then by the Supreme Court in September. Two days before Imdad Ali was due to be hung, his execution was temporarily stayed by the Supreme Court.

Out of the 14 years Ali has spent on death row, the last three have been spent in solitary confinement. These numbers are staggering even when considered without the fact that Imdad Ali was officially declared a paranoid schizophrenic by the head of psychiatry, Dr Naeemullah Leghari, at Nishtar Hospital in 2012.

“There was history of self-talk, gesturing, posturing, odd ideas and beliefs, bizarre ideations and lack of concern for his death sentence,” Dr Leghari told the Justice Project Pakistan. “During his stay in the ward… [h]is mental state exam was significant for: Lack of self care, incoherent speak (lacking clarity) .... He had bizarre paranoid delusions and also had incongruent grandiose delusions. He had no insight into the illness.” Imdad Ali’s mental status and the fact that he was diagnosed with genetic paranoid schizophrenia did not sway the Supreme Court. Paradoxically, it explicitly rejected schizophrenia as a mental illness.

The year Ali was tried and convicted by the sessions court, 200 miles away, another case was registered in Rahimyar Khan. The case involved the abduction and rape of Salma, the daughter of a man called Ghulam Qadir, and the subsequent murders of Salma, Abdul Qadir, and his son, Akmal. It was suspected to be a case of a family enmity.

In 2005, Out of at least eight people arrested and put on trial, six nominated accused people were released. One of them was handed down a double life imprisonment sentence and the two brothers, Ghulam Qadir and Ghulam Sarwar, were convicted and sentenced to death. The decision was upheld by the Bahawalpur Bench of the Lahore High Court.

On June 10, 2010, the Ghulam brothers filed leave to appeal in the Supreme Court where a two-judge bench only granted leave to re-examine evidence pertaining to Salma. The death sentence remained unchanged for the other two murders. Here onwards, the case’s trajectory take a confusing and terrifying turn.

Six years later, a different SC bench took up the case. Upon revisiting the last SC order and finding inconsistencies in it, they decided that they would exercise their suo moto right to reassess the evidence for all three murders, for the entire case. The honourable judges found glaring, material contradictions in the evidence of the prosecution witnesses and declared that the prosecution had miserably failed to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt. The brothers were free to go.

The news of their acquittal never reached them. After spending the last decade of their lives on death row, both Ghulam Qadir and Ghulam Sarwar were wrongfully executed in October 2015, exactly a year before they were exonerated.

Bottom up: pre-trial investigations & trials

Many questions arise from the major lapses in due process and the lack of application of sound, legal reasoning at all levels. The most uncomfortable questions, however, can be traced to the beginning of both cases, and all criminal cases in general: This is the substandard, unprofessional pre-trial investigation and trial practices you will find in our lower courts.

In Imdad Ali’s case, we have been quick to deconstruct the Supreme Court’s most recent parochial order, which seemingly expels schizophrenia from qualifying as a ‘mental disorder’ according to the definition of the Mental Health Ordinance, 2001, ironically enacted the same year Imdad Ali’s life was incarcerated. Yet, we have failed to examine why his illness was only officially examined and noted by the courts in 2012—10 years too late. The Imdad Ali case encapsulates the indelible nature of evidence recorded at the trial level. If you don’t get it right the one time, your chances of walking out a free man are slim.

At the trial level, not only was the plea of insanity indirectly raised during cross-examination, but Imdad’s own wife testified to his unsound mind. Defence witnesses, let alone women, rarely take the stand in murder trials in Pakistan, so this in itself was significant. Sadly, these were perhaps the only steps that could have been taken by Imdad Ali, since his family could not afford the service of a professional medical expert.

While confirming Imdad’s death sentence, the judge stated the following: “If the learned trial judge himself would have felt that the appellant was not (a) normal person, he could himself [have] take notice of [it].” He was perhaps not aware of the litmus test used to assess the sanity of mentally ill prisoners in our courts: ‘Please state your name’. If the accused answers correctly, he is deemed sane.

Pakistan has a broken criminal justice system. Our top courts are overburdened and under resourced and lower courts are even more so. Add to this the substandard quality of investigations, apathetic and underpaid defence lawyers and a lack of systematized legal aid for poor clients and you have a perfect recipe for disaster.

The case of the two brothers is also illustrative of these shortcomings. Once a crime is allegedly committed by someone, the wheels of our broken criminal justice system come into motion. Someone must be punished. It is a dangerous and sadly common pressure tactic and modus operandi, for the complainants (people who register the case) to cast a wide net and implicate as many people (usually relatives) as possible. The complainants are further emboldened by a penal system and overzealous police officials. The formula is: implicate as many people as possible because at least a few will be convicted and sentenced to death.

If you are implicated for murder, your chances of conviction at the trial stage are staggeringly high. It is perhaps convenient for the lower courts to send cases up to the high courts, passing on the responsibility of sifting through and acquitting dangerous, hardened criminals, juveniles and the mentally ill. Once up, death penalty cases are weeded out at the appellate stage, with most sentences being commuted to life and in some cases, acquittals. But how do we make it up to men and women who have lost decades behind bars?

“There are a number of problems in the system,” remarks defence counsel Asad Jamal. “True, that it’s convenient for judges of lower courts to transfer the burden to the higher fora, but they’re also scared of being labeled ‘corrupt’ or soft. Their training and the system they work in and survive in is based on the idea of subservience and obedience to the higher authority. Their training doesn’t impart them confidence.” An HRCP report substantiates this trend. From December 2014 (when the unofficial moratorium was lifted) to date, 359 people were sentenced to death by sessions courts compared to 107 in the high court.

However, according to Asad, the problem also lies with jurisprudence of the higher courts. “The supreme court’s death penalty jurisprudence is, in more ways than one, based in large part on the assumption that judges can be counted on to apply the law conscientiously and fairly,” he says. “In some cases, the Supreme Court has gone to the extent of saying that establishing motive was not necessary to award the death penalty. This shows how little value our judges attach to human life.”

This sends a strange message to trial judges, who instinctively gravitate towards awarding the death penalty. There is a trickle-down effect of this malaise of ineptitude, the police is lazy, the prosecution is lazy. No one is held accountable. “Therefore, there’s every likelihood that the innocent may go through unjustified imprisonment before they’re acquitted or may be hanged because some of the cases escaped careful scrutiny even at the highest forum,” states Asad Jamal.

Appellate courts will very seldom reevaluate the facts of a case; that is the trial court’s job. Schizophrenic Imdad Ali’s fate was sealed during his trial as all appellate courts thereafter refused to invite any new facts. Had the issue of his state of mind been explored more deeply at the trial level, we would perhaps not be in this bind.

Top-down breakdown

October 2016 will go down as historic in its exposé of the deep-rooted, systemic, gaping flaws in Pakistan’s criminal justice system. An even more troubling certainty is that the apex courts have let us down in equal measure, if not more.

It is absolutely outrageous and unacceptable that two men were made to walk the gallows, only to be exonerated a year later. In a cruel twist of fate, owing to the unavailability of an executioner in Rahim Yar Khan, the brothers were moved to Bahawalpur. The State and its functionaries are trained to only dispense punitive injustices, it seems.

In the case of Imdad Ali, the Supreme Court bench was provided with the chance to deliver an important judgment on mental illness and its association with criminal behaviour. The apex court failed to deliver. Or perhaps there is still a glimmer of hope left.

“In Pakistan, we are not only subject to a criminal justice system that prescribes the death penalty for 27 crimes, but one that is beset with inefficiencies and corruption,” says Maryam Haq, the legal director of Justice Project Pakistan. “This system is unacceptable for so harsh and irreversible a punishment that has already been meted out to 420 people since December 2014.” This macabre record includes juveniles, the mentally ill and innocent people who were tortured into making confessions.

In the Bahawalpur case, the two brothers were acquitted a year after they were hanged, even though they maintained their innocence until the very end. Ghulam Sarwar and Ghulam Qadir were failed by the law, and Imdad Ali came within inches of the noose under the same system. Haq adds, though, that “Unfortunately, neither of the two cases are aberrations.”

The writer is a lawyer. She works at the Public Interest Law Association of Pakistan (PILAP) as their legal counsel. She can be reached at noorzafar7@gmail.com