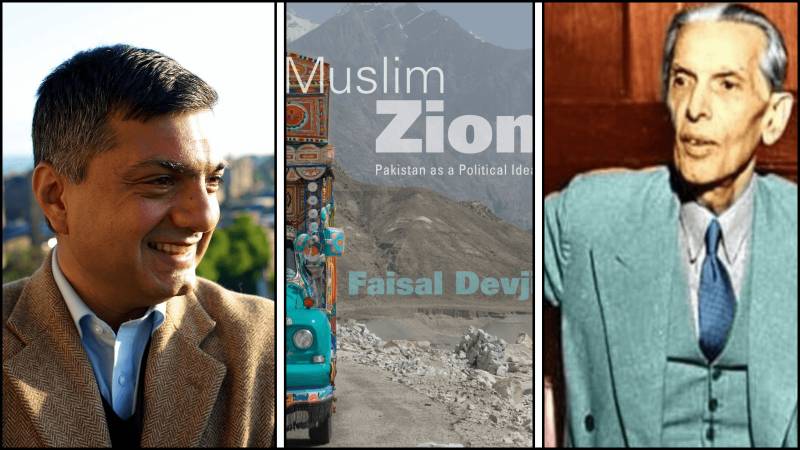

I read with interest Professor Faisal Devji's response here to a review in Dawn of his classic Muslim Zion.

When it came out ten years ago, I was among the first to respond with a knee-jerk in one of the articles I wrote on it. After all, calling Mr Jinnah "satanic" and "Devilish", and equating the Muslim nationalism that led to the creation of Pakistan to Zionism was, on first impression, unacceptable to any Pakistani worth his or her salt. So, I am not surprised that ten years later, the book continues to evoke patriotic outrage amongst Pakistanis. I had the opportunity to revisit the book when I was writing my book on Mr Jinnah and have gone back to it to understand the puzzle that is our homeland.

Professor Devji is a historian of ideas and, as such, believes in taking ideas seriously, which is commendable. For long, Pakistan has carried the stigma of being "insufficiently imagined". Regardless of the debate on what form Pakistan could have taken, be it within a confederation of India or as a separate state as it eventually turned out, the underlying idea of what Pakistan represented and what it meant to its main protagonist is one that remains relevant to Pakistan's many current predicaments.

Muslim Zion provided me with the vocabulary I did not have when describing the central idea behind Pakistan. For long, one has argued against the idea that Pakistan was created in the name of Islam, i.e., to enforce God's law and enforce the practice of the Islamic faith. Why was it that some of the proponents of the Pakistan idea, most notably Jinnah himself, were either irreligious or too modern to be concerned with rituals and Islamic conventions? The profane explanation is that the Aligarh school of Muslim modernists and the Muslim elites were cynically using religion for politics, power and personal gain. Muslim Zion has a different explanation. What Devji argues is that the "Islam"- as deployed by the All-India Muslim League- was ontologically emptied and not a "religion" in so much as religion means theology, rituals and practice. It was this empty husk that allowed "Muslims" of all kinds, including those who might have been atheists or agnostics, to come together and make their clarion call for sovereignty. It also explains the almost universal animosity that these "Muslims" evoked amongst the orthodox including those who denounced Pakistan as "Kafiristan" and its main proponent Mr Jinnah as "Kafir-e-Azam". How Jinnah went from being an "Indian first second and last" to a leader who espoused this "empty Islam" has been discussed to death elsewhere and I will spare the readers a repetition of the facts. What Muslim Zion stipulates has profound implications not just for Pakistan.

The Devil represents a fierce individuality, and as Professor Devji points out, Jinnah was more devilish than the Devil because, unlike the Devil, Jinnah refused to tempt people. That was the hallmark of the Quaid-e-Azam. He didn't paint an alluring portrait of Pakistan to deceive his followers

Professor Devji talks of a "secularised Islam" and the Jinnah moment for Muslim politics that had reformative potential which could be of great value to Muslim-majority societies around the globe. Devji argues that the underlying nationalism in Pakistan was enlightenment nationalism and not romantic nationalism. This is important because far from reducing the Pakistan idea to crass medieval religious nationalism, it elevates it to a nationalism of ideas. One can always question whether a certain idea is right or wrong, but the basic idea behind Pakistani enlightenment nationalism was that this modernist and secularised Islam, i.e. Islam ontologically emptied and not the Islam that was an old-world religion, which could foretell an egalitarian, inclusive and modern society. This is where the largely modernist framers of the Objectives Resolution in 1949 went terribly wrong. Religious language and nod to God's sovereignty in constitutional preambles is not unique to Pakistan (indeed many secular democracies like Canada, Ireland, Denmark, etc have similar language in their constitutions- it is what American jurisprudence describes as ceremonial deism) but it was when the resolution begins to speak of enabling the Muslim population to live according to Quran and Sunnah, that the ceremonial deism is given positive theological content. Hence, the confusion around the origins of the state which has plagued constitution-making in Pakistan's patchy political history.

As for Devji's description of Jinnah as devilish, it is an echo of M N Roy's famous description of Jinnah's career as Mephistophelian in his very sympathetic obituary of the man from 1948. The Devil is the great anti-hero, and even a tragic hero, of the Abrahamic tradition. Iqbal, as Professor Devji points out, celebrates the Devil as the epitome of individuality and purposeful action, especially when we consider Iqbal's poem Jibrail o Iblis. The Devil represents a fierce individuality, and as Professor Devji points out, Jinnah was more devilish than the Devil because, unlike the Devil, Jinnah refused to tempt people. That was the hallmark of the Quaid-e-Azam. He didn't paint an alluring portrait of Pakistan to deceive his followers and resorted to none of the rhetorical flourishes that were the hallmark of populist politicians of the time. One would imagine that for a leader leading Muslims - extremely emotional ones at that - his speeches should've been peppered with quotes from the scripture, Hadith and the Islamic canon. Jinnah's speeches had none of that. Even his great rival, Gandhi, quoted the Holy Quran and gave examples from the lives of the Caliphs on occasion, but Jinnah did none of that. Jinnah's exposition of the Muslim case was unemotional, constitutional and legalistic.

In many ways, Jinnah was simply the barrister pleading his clients' case without sharing their basic beliefs. This explains why one of the first acts of Jinnah as the founder of Pakistan was to insist on Pakistani oaths of office to be secular affirmations, dropping even the perfunctory reference to God in them. Evidently, even ceremonial deism was unacceptable to Jinnah. It is, therefore, not surprising that Jinnah chose to model the constitution he was drafting for Pakistan on the French Republic, which is the one exception to the general rule of acceptability of ceremonial deism in Anglo-Saxon and other European constitutional and legal systems. Nehru, in his book Discovery of India, describes Jinnah as far more advanced in his thought and someone who stood head and shoulders above his colleagues in the Muslim League. This is why Jinnah cut a solitary and distant figure – someone who had, amongst Muslims, only associates and never friends.

Professor Faisal Devji's work provides a thought-provoking perspective on Pakistan's creation and its relation to Islam. Rather than reducing the country's foundation to mere religious nationalism, Prof Devji offers an intellectual framework that elevates Pakistan's underlying ideology to a nationalism of ideas—one based on a secularised, ontologically emptied Islam, which, while not centred on theology or ritual, became the unifying force for Muslims of all stripes. This interpretation, though provocative, allows us to reconsider Jinnah's vision and the ideological struggle Pakistan has faced since its inception.