On 11 August 1947, just three days before Pakistan was born, M. A. Jinnah, the founder, spoke to the Constituent Assembly: “[In] course of time all these angularities of the majority and minority communities, the Hindu community and the Muslim community -- because even as regards Muslims you have Pathans, Punjabis, Shias, Sunnis and so on, and among the Hindus you have Brahmins, Vaishnavas, Khatris, also Bengalees, Madrasis and so on -- will vanish.”

Later, he spoke what are quite possibly his most frequently quoted words: “You are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed -- that has nothing to do with the business of the State. [You] will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus, and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State.”

Consistent with that vision, his cabinet included a Hindu and an Ahmadi. Jinnah had created Pakistan as a separate homeland for the Muslims of British India in August 1947 simply to prevent them from becoming a permanent minority in post-British India whose population would be overwhelmingly Hindu.

Jinnah was schooled in the traditions of parliamentary democracy, where there was no room for military rule. And he led a secular lifestyle, with no interest in creating a theological state. There is no evidence that he offered the five daily prayers or observed the fasts of Ramadan. He did not travel to Makkah to perform either the lesser or the greater pilgrimage. Unsurprisingly, he admired Turkey’s secular founder, Kamal Ataturk.

The last thing he wanted to do was to create a state that would be based on Islamic ideology, let alone a state whose most powerful institution would be the army.

Yet that’s what Pakistan ended up becoming. Today’s Pakistan bears no resemblance to Jinnah’s vision. It proudly calls itself an Islamic Republic where anyone who is accused of blasphemy can be put to death, if not by the state, then by a violent mob. It’s a state where the army calls the shots, going back to 1958, when the first coup took place.

How did Pakistan lose its way? Answering that question is just as complex as resolving the riddle of the sphinx. Myriads of academics, scholars and journalists have written books, scholarly papers and newspapers articles on why Pakistan lost its way.

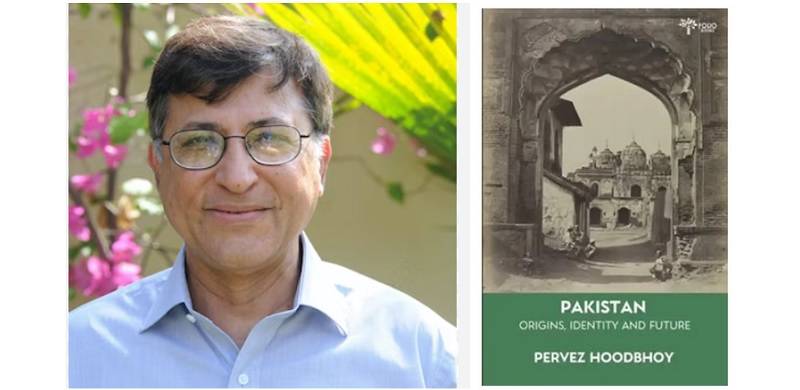

In his book Pakistan: Origins, Identity and Future, Pervez Hoodbhoy takes that question head on. He is not a historian or a political scientist but a professor of physics. Remarkably, he is also one of Pakistan’s most prolific political commentators.

I owe him a personal debt. Soon after the invasion of Kargil, I wrote a piece, “The Price of Strategic Myopia,” and circulated it for comment to dozens of experts around the globe, including Henry Kissinger and Amartya Sen, both of whom acknowledged receiving it, and General Zinni, head of the US Central Command. Several others such as Stephen Cohen of Brookings provided comments.

Dr. Hoodbhoy went a step further. He liked it so much that he recommended it to Beena Sarwar who published it in The News on Sunday. A few years later, it grew into a book, Rethinking the National Security of Pakistan: The Price of Strategic Myopia, which was published in England by Ashgate and was reissued in 2020 by Routledge Revivals. Along the way, it was cited by the Abbottabad Commission into the US killing of Osama bin Laden.

Given how much has already been written on the topic of origins, identity and future of Pakistan, I was not sure what new material I would find in Hoodbhoy’s book. Well, I was pleasantly surprised. Even when he is treading ground that’s already well-trodden, he brings a unique perspective to bear on it. In addition, he uncovers new source material and sheds new light on the subject.

The book is a veritable tour de force, meticulously researched, and an easy read. It does not suffer from the academic jargon that so often permeates the writings of academics. His narration of Pakistan’s history is often tinged with pathos.

He documents in meticulous detail how Islam, the common religion of its inhabitants, proved to be a weak foundation for Pakistan. It could not bridge the gap of a thousand miles between the two wings, or the gaps of language, ethnicity and culture between the provinces of the western wing. One province came to dominate the other three, which were often called minority provinces, as a former army chief once told me.

The word Pakistan was an acronym in which the various letters stood for its various provinces. Hoodbhoy reminds us that Afghanistan and Kashmir were included in the acronym but never became part of the country. Oddly, Bengal, where the majority of the population, was not even in the acronym.

Pakistan was also a word taken from Persian, meaning the pure land. Hoodbhoy quotes Maulana Azad: “I must confess that the very term Pakistan goes against my grain. It suggests that some portions of the world are pure while others are impure. Such a division of territories into pure and impure is un-Islamic … and a division which is a repudiation of the very spirit of Islam.”

Jinnah succeeded in creating Pakistan but the trauma of Partition was far worse than anyone had imagined. The Radcliffe line had been drawn in haste. Panic spread among millions as the deadline approached. They did not want to be on the wrong side of the border. As they sought to cross the newly created border, as many as a million people may have perished and countless millions traumatised for life.

Partition was supposed to defuse intercommunal conflicts between Muslims and Hindus. Instead, the conflict escalated and turned into an international conflict between Pakistan and India. Numerous major and minor wars would follow in the decades that followed. Within Pakistan, it bred intercommunal conflicts between ethnicities and religious minorities such as Christians and Hindus and ultimately between Muslim sects. The “angularities” that Jinnah had talked about in his 11th-August speech refused to go away. In fact, they became even more pronounced.

Hoodbhoy brings out the toll that Pakistan’s obsession with acquiring Kashmir has taken on its economic and social development. It also brings out the lack of interest that Pakistan’s leaders, just about all of whom hailed from West Pakistan, took in the development of East Pakistan. It was viewed as the poor sibling and was often the subject of racial slurs. The first sign of contempt for Bengali values was the imposition of Urdu as the state language by Jinnah himself. Bengali dress and cuisine were derided as was the appearance of the typical person from Bengal. Unsurprisingly, being treated poorly fueled resentment in East Pakistan that would grow with time.

Less than a quarter century after independence from Great Britain, it exploded. East Pakistan seceded after a horrific civil war which reached its climax when India invaded and conquered it in less than a fortnight. This happened during military rule. Of course, General Yahya, the second military ruler, blamed it amazingly on “the treachery of the Indians.”

ZA Bhutto, the leader of the largest party in the western province, was sworn in as president and later elected as the prime minister by the (truncated) national assembly. As part of a compromise with the religious parties, members of the Ahmadi faith were declared non-Muslims.

The religious gene had made its presence felt as far back as 1956 when Pakistan was declared an Islamic Republic during civilian rule. But governments did not do much to pass and implement Islamic Law in the country. That would come to pass during the tenure of General Zia, the third military ruler. He had risen to fame because of the role that the Pakistani military played in concert with the US to evict the Soviets from Afghanistan. A militia known as the Mujahideen were created to carry out a guerilla war. They were armed and trained by the Pakistani military and funded by the US and the Saudi’s.

Religion was glorified and soon turned into state policy by Zia, who was a pious Muslim. He played to the religious sentiments of millions in the population and introduced Islamic Law. Public floggings made the headlines. Signs began to appear on street lights with a grave reminder: Say your prayers before your (funeral) prayers are offered. Workers in their workplaces began to take a break for congregational prayers, which was a common practice in Saudi Arabia. Arabic began to be introduced in everyday discourse. The common goodbye greeting, Khuda Hafiz, was replaced with Allah Hafiz, which is not even used in Arab countries. Arabic words replaced Persian words even in the names of major boulevards.

Thus, its no surprise that not too long ago a sporting legend who had been floundering in politics for years and who was an internationally well-known playboy suddenly rose to prominence on the national scene by calling for the creation of an Islamic Welfare State. He was installed as prime minister in 2018 at the behest of the army. His rule ended abruptly three and a half years later when he crossed paths with the army.

In his various speeches since being removed from office, he is often seen holding prayer beads in his left hand and reciting frequently the fourth verse from the first chapter of the scripture. To further convey his religiosity, he has married a woman who remains shrouded in mystery, both physically and metaphorically.

In the book, an entire chapter is devoted to how Pakistan became a Praetorian state. As with the other chapters, it sheds new light on a much examined topic. The topic is so rich in complexity that it could be the topic of an entire book.

Hoodbhoy also touches on how Pakistan’s economy lost out to India’s economy from 1991 onwards and how it also lost out to Bangladesh’s economy a few years ago, even in the field of textiles where Pakistan had held sway in international markets for decades. That’s the reality, despite Goldman Sachs making a tall forecast that Pakistan will be one of the world’s leading economies by 2075.

Looking at the future, Hoodbhoy makes a number of important recommendations: make peace with neighbors, let civilians run the country, decentralise massively, choose trade over aid, redirect education toward skill enhancement and enlightenment, stop political and religious indoctrination, give women a voice, allow labor and unions a role in the democratic process, eliminate large land holdings, collect land and property taxes based upon current market value, speed up the courts and make them transparent, make meritocratic appointments in government.

Hardly anyone would disagree with those recommendations. They have been made by others for decades. So, why have they not been implemented? Obviously, real barriers stand in the way. Those who would lose if they were implemented hold the strings of power. Why would they voluntarily surrender their privileges? Without discussing these issues, Hoodbhoy’s reform agenda comes across as a bit Utopian. I am equally guilty. I had also put out a way forward, knowing fully well the odds of its being realised are in the neighborhood of zero. Predicting Pakistan’s future is an impossible task.

Another question not addressed in the book is whether martial law would not have been implemented if Pakistan had been blessed with competent leaders between 1949 and 1958. The justification that Ayub gave for imposing martial law was the incompetence and corruption of the civilian rulers that had succeeded Jinnah. How much of the blame can be placed on the US for providing arms and training to the Pakistani military as part of enlisting Pakistan in the Cold War?

India had Nehru at the helm during that period (and for a few more years until he died). Would things have been different if Jinnah had lived as long as Nehru? Not many knew he had tuberculosis but he did. Why did he not pick better successors? Or did he think the people around him were capable of leading Pakistan after he had gone? In her book Indian Summer, Alex von Tunzelmann says that Jinnah told his doctor on deathbed that “Pakistan was the biggest blunder of his life.” Is there any truth to that?

Was Partition a terrible idea to begin with that was doomed to fail? Was it, as Faisal Devji puts it, a Muslim Zion, fated to endless conflicts with its neighbors? Or, was it a good idea that was poorly implemented? Would East Pakistan have stayed in the federation if Urdu had not been imposed on them and if Bengalis had been well represented in senior government positions, including in the military, and given their fair share of the national budget?

Would Pakistan’s evolution have been different if the Kashmir issue had been successfully resolved at the time of Partition?

Would religiosity have been kept out of the body politic if the Soviet Union not invaded Afghanistan?

Would a third round of martial law not have happened if Bhutto had appointed someone other than General Zia as army chief and if he had not authorised the rigging of the polls in 1977?

Perhaps Professor Hoodbhoy can speculate about these “What If” questions in his next book. Even without addressing these issues, his book is a major contribution to the burgeoning literature on Pakistan, a worthy addition to all academic libraries, and a must-read for those seriously interested in the past, present and future of Pakistan.

Later, he spoke what are quite possibly his most frequently quoted words: “You are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed -- that has nothing to do with the business of the State. [You] will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus, and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State.”

Consistent with that vision, his cabinet included a Hindu and an Ahmadi. Jinnah had created Pakistan as a separate homeland for the Muslims of British India in August 1947 simply to prevent them from becoming a permanent minority in post-British India whose population would be overwhelmingly Hindu.

Jinnah was schooled in the traditions of parliamentary democracy, where there was no room for military rule. And he led a secular lifestyle, with no interest in creating a theological state. There is no evidence that he offered the five daily prayers or observed the fasts of Ramadan. He did not travel to Makkah to perform either the lesser or the greater pilgrimage. Unsurprisingly, he admired Turkey’s secular founder, Kamal Ataturk.

The last thing he wanted to do was to create a state that would be based on Islamic ideology, let alone a state whose most powerful institution would be the army.

Yet that’s what Pakistan ended up becoming. Today’s Pakistan bears no resemblance to Jinnah’s vision. It proudly calls itself an Islamic Republic where anyone who is accused of blasphemy can be put to death, if not by the state, then by a violent mob. It’s a state where the army calls the shots, going back to 1958, when the first coup took place.

How did Pakistan lose its way? Answering that question is just as complex as resolving the riddle of the sphinx. Myriads of academics, scholars and journalists have written books, scholarly papers and newspapers articles on why Pakistan lost its way.

In his book Pakistan: Origins, Identity and Future, Pervez Hoodbhoy takes that question head on. He is not a historian or a political scientist but a professor of physics. Remarkably, he is also one of Pakistan’s most prolific political commentators.

I owe him a personal debt. Soon after the invasion of Kargil, I wrote a piece, “The Price of Strategic Myopia,” and circulated it for comment to dozens of experts around the globe, including Henry Kissinger and Amartya Sen, both of whom acknowledged receiving it, and General Zinni, head of the US Central Command. Several others such as Stephen Cohen of Brookings provided comments.

Dr. Hoodbhoy went a step further. He liked it so much that he recommended it to Beena Sarwar who published it in The News on Sunday. A few years later, it grew into a book, Rethinking the National Security of Pakistan: The Price of Strategic Myopia, which was published in England by Ashgate and was reissued in 2020 by Routledge Revivals. Along the way, it was cited by the Abbottabad Commission into the US killing of Osama bin Laden.

Given how much has already been written on the topic of origins, identity and future of Pakistan, I was not sure what new material I would find in Hoodbhoy’s book. Well, I was pleasantly surprised. Even when he is treading ground that’s already well-trodden, he brings a unique perspective to bear on it. In addition, he uncovers new source material and sheds new light on the subject.

The book is a veritable tour de force, meticulously researched, and an easy read. It does not suffer from the academic jargon that so often permeates the writings of academics. His narration of Pakistan’s history is often tinged with pathos.

He documents in meticulous detail how Islam, the common religion of its inhabitants, proved to be a weak foundation for Pakistan. It could not bridge the gap of a thousand miles between the two wings, or the gaps of language, ethnicity and culture between the provinces of the western wing. One province came to dominate the other three, which were often called minority provinces, as a former army chief once told me.

The word Pakistan was an acronym in which the various letters stood for its various provinces. Hoodbhoy reminds us that Afghanistan and Kashmir were included in the acronym but never became part of the country. Oddly, Bengal, where the majority of the population, was not even in the acronym.

Pakistan was also a word taken from Persian, meaning the pure land. Hoodbhoy quotes Maulana Azad: “I must confess that the very term Pakistan goes against my grain. It suggests that some portions of the world are pure while others are impure. Such a division of territories into pure and impure is un-Islamic … and a division which is a repudiation of the very spirit of Islam.”

Jinnah succeeded in creating Pakistan but the trauma of Partition was far worse than anyone had imagined. The Radcliffe line had been drawn in haste. Panic spread among millions as the deadline approached. They did not want to be on the wrong side of the border. As they sought to cross the newly created border, as many as a million people may have perished and countless millions traumatised for life.

Partition was supposed to defuse intercommunal conflicts between Muslims and Hindus. Instead, the conflict escalated and turned into an international conflict between Pakistan and India. Numerous major and minor wars would follow in the decades that followed. Within Pakistan, it bred intercommunal conflicts between ethnicities and religious minorities such as Christians and Hindus and ultimately between Muslim sects. The “angularities” that Jinnah had talked about in his 11th-August speech refused to go away. In fact, they became even more pronounced.

Hoodbhoy brings out the toll that Pakistan’s obsession with acquiring Kashmir has taken on its economic and social development. It also brings out the lack of interest that Pakistan’s leaders, just about all of whom hailed from West Pakistan, took in the development of East Pakistan. It was viewed as the poor sibling and was often the subject of racial slurs. The first sign of contempt for Bengali values was the imposition of Urdu as the state language by Jinnah himself. Bengali dress and cuisine were derided as was the appearance of the typical person from Bengal. Unsurprisingly, being treated poorly fueled resentment in East Pakistan that would grow with time.

Less than a quarter century after independence from Great Britain, it exploded. East Pakistan seceded after a horrific civil war which reached its climax when India invaded and conquered it in less than a fortnight. This happened during military rule. Of course, General Yahya, the second military ruler, blamed it amazingly on “the treachery of the Indians.”

ZA Bhutto, the leader of the largest party in the western province, was sworn in as president and later elected as the prime minister by the (truncated) national assembly. As part of a compromise with the religious parties, members of the Ahmadi faith were declared non-Muslims.

The religious gene had made its presence felt as far back as 1956 when Pakistan was declared an Islamic Republic during civilian rule. But governments did not do much to pass and implement Islamic Law in the country. That would come to pass during the tenure of General Zia, the third military ruler. He had risen to fame because of the role that the Pakistani military played in concert with the US to evict the Soviets from Afghanistan. A militia known as the Mujahideen were created to carry out a guerilla war. They were armed and trained by the Pakistani military and funded by the US and the Saudi’s.

Religion was glorified and soon turned into state policy by Zia, who was a pious Muslim. He played to the religious sentiments of millions in the population and introduced Islamic Law. Public floggings made the headlines. Signs began to appear on street lights with a grave reminder: Say your prayers before your (funeral) prayers are offered. Workers in their workplaces began to take a break for congregational prayers, which was a common practice in Saudi Arabia. Arabic began to be introduced in everyday discourse. The common goodbye greeting, Khuda Hafiz, was replaced with Allah Hafiz, which is not even used in Arab countries. Arabic words replaced Persian words even in the names of major boulevards.

Thus, its no surprise that not too long ago a sporting legend who had been floundering in politics for years and who was an internationally well-known playboy suddenly rose to prominence on the national scene by calling for the creation of an Islamic Welfare State. He was installed as prime minister in 2018 at the behest of the army. His rule ended abruptly three and a half years later when he crossed paths with the army.

In his various speeches since being removed from office, he is often seen holding prayer beads in his left hand and reciting frequently the fourth verse from the first chapter of the scripture. To further convey his religiosity, he has married a woman who remains shrouded in mystery, both physically and metaphorically.

In the book, an entire chapter is devoted to how Pakistan became a Praetorian state. As with the other chapters, it sheds new light on a much examined topic. The topic is so rich in complexity that it could be the topic of an entire book.

Hoodbhoy also touches on how Pakistan’s economy lost out to India’s economy from 1991 onwards and how it also lost out to Bangladesh’s economy a few years ago, even in the field of textiles where Pakistan had held sway in international markets for decades. That’s the reality, despite Goldman Sachs making a tall forecast that Pakistan will be one of the world’s leading economies by 2075.

Looking at the future, Hoodbhoy makes a number of important recommendations: make peace with neighbors, let civilians run the country, decentralise massively, choose trade over aid, redirect education toward skill enhancement and enlightenment, stop political and religious indoctrination, give women a voice, allow labor and unions a role in the democratic process, eliminate large land holdings, collect land and property taxes based upon current market value, speed up the courts and make them transparent, make meritocratic appointments in government.

Hardly anyone would disagree with those recommendations. They have been made by others for decades. So, why have they not been implemented? Obviously, real barriers stand in the way. Those who would lose if they were implemented hold the strings of power. Why would they voluntarily surrender their privileges? Without discussing these issues, Hoodbhoy’s reform agenda comes across as a bit Utopian. I am equally guilty. I had also put out a way forward, knowing fully well the odds of its being realised are in the neighborhood of zero. Predicting Pakistan’s future is an impossible task.

Another question not addressed in the book is whether martial law would not have been implemented if Pakistan had been blessed with competent leaders between 1949 and 1958. The justification that Ayub gave for imposing martial law was the incompetence and corruption of the civilian rulers that had succeeded Jinnah. How much of the blame can be placed on the US for providing arms and training to the Pakistani military as part of enlisting Pakistan in the Cold War?

India had Nehru at the helm during that period (and for a few more years until he died). Would things have been different if Jinnah had lived as long as Nehru? Not many knew he had tuberculosis but he did. Why did he not pick better successors? Or did he think the people around him were capable of leading Pakistan after he had gone? In her book Indian Summer, Alex von Tunzelmann says that Jinnah told his doctor on deathbed that “Pakistan was the biggest blunder of his life.” Is there any truth to that?

Was Partition a terrible idea to begin with that was doomed to fail? Was it, as Faisal Devji puts it, a Muslim Zion, fated to endless conflicts with its neighbors? Or, was it a good idea that was poorly implemented? Would East Pakistan have stayed in the federation if Urdu had not been imposed on them and if Bengalis had been well represented in senior government positions, including in the military, and given their fair share of the national budget?

Would Pakistan’s evolution have been different if the Kashmir issue had been successfully resolved at the time of Partition?

Would religiosity have been kept out of the body politic if the Soviet Union not invaded Afghanistan?

Would a third round of martial law not have happened if Bhutto had appointed someone other than General Zia as army chief and if he had not authorised the rigging of the polls in 1977?

Perhaps Professor Hoodbhoy can speculate about these “What If” questions in his next book. Even without addressing these issues, his book is a major contribution to the burgeoning literature on Pakistan, a worthy addition to all academic libraries, and a must-read for those seriously interested in the past, present and future of Pakistan.