The idea of a homeland has consolidated so much in the modern human imagination that people often do not realize how fluid is the concept, and a bit overrated as well.

Homeland is equated with origin, which over years has turned into an important category to identify people. But homelands may often not be homes. People can equate lands with home but that can have nothing to do with their origins. They may even be forced to return ‘home’, as in a place of their origin, and yet yearn for the ‘home’ they had to abandon, and in the process never settle down emotionally.

I began to understand the nature of a dichotomous identity when I first met the flamboyant Nadira Naipaul, the wife of V. S. Naipaul, in Bahawalpur during the late 1980s. She was then Nadira Mustafa and lived there with her two children and her then landowner husband, the (late) Iqbal Mustafa, warming the hearts of the town with her presence. When I asked her about the place of origin of her family, I didn’t get an answer that I was used to: My family is from Kenya. She was not African, but that was very much ingrained in her identity.

Hers was one of the many families who were forced to leave their homes to either settle in the West or come to countries associated with their origin. These people were part of the hundreds and thousands of Indians who were taken by the British as professional or unskilled workers to African colonies where they lived and prospered, even setting up their own businesses until Africa started to gain its independence. It was the era of post-2nd World War de-colonization and the emergence of new nation-states and nationalism, in which leaders naturally keeled over towards populism that led them towards a policy of ‘Africanization’. Consequently, Europeans and Indians (that’s how South Asians were generally identified) were evicted. It was a traumatic experience for many, who were forced to leave behind everything they had worked for. Idi Amin, for instance, gave these people, who had British travel documents, the choice to either renounce these documents or leave in 90 days. For those who opted to stay, things didn’t get better either as they were up against discrimination.

While many people migrated to Europe and the Americas, some came to countries carved out of the Subcontinent. Yet there is very little written about them or visualized in art in Pakistan about their personal traumas of that migration. To be fair, not a lot has been written even about the trauma of forced migration of Pakistanis from Bangladesh after 1971. Thus, it is quite probable that public discourse will ignore the evolving tragedy of hundreds and thousands of families currently undergoing (almost) forced eviction from Saudi Arabia. These people are not been given any timeframe to leave but they know it is not longer easy to remain in the Kingdom where they spent decades and invested in a future.

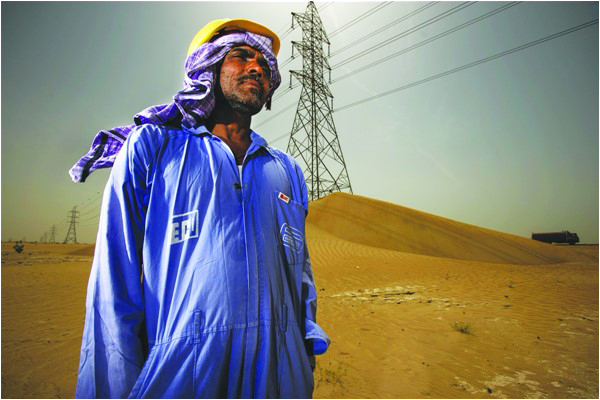

The decision by Riyadh to impose a tax of about Saudi Riyals 200 on every foreign individual, referred to in Arabic as ajnabi (stranger) has forced hundreds of Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis to send their families home if not return altogether. Now it is either men being torn from their families, or making a choice to live in Saudi Arabia legally but struggle to survive in the face of the ‘Saudization’ of the economy as per ‘Vision 2030’ rolled out by the new prince-king.

Reportedly, General (retd) Raheel Sharif tried to give hope to some journalists he had invited from Pakistan at the end of last year to Riyadh. He had indicated that the military coalition would bring numerous benefits to Pakistan, such as the possibility of visa-free entry for member states of the Saudi-funded military coalition. While this may be his understanding, the facts speak otherwise. Saudi Arabia is not keen to import or retain un-skilled labour from Pakistan or other parts of South Asia. In 2017 about 64,689 Pakistanis were evicted from the Kingdom. While many of these people were fairly new migrants who had overstayed their visas or were working illegally, the situation is not good even for those who have lived there longer.

Pakistanis or South Asian Muslims in general have a long association with Saudi Arabia. There were scholars and their families who had settled there during the 1930s and the 1940s. Even today you find houses with the names al-Hindi and al-Sindhi written on the front. Later, as the Saudi state started to evolve with the discovery of crude oil, Pakistani experts played an important role in the evolutionary process. For instance, Pakistani economist Anwar Ali became the head of the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) in 1957, an organization that controls all the resources of the Kingdom and works as its central bank. He remained in the position until 1974. There were many others skilled workers often with an ideological affinity with the Jamaat-e-Islami who worked in various parts of the country.

There was a historically close association between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, which was consciously cultivated by the latter with help from the US and UK. As a result citizenship was conferred on many Pakistanis during the decades of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. However, unlike the British, American or European citizenship, Saudi citizenship cannot be inherited if children do not reside in the Kingdom for a certain period.

A larger tranche of Pakistanis came during the 1970s and later. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto cultivated relations with the Arab Middle East, especially Saudi Arabia and Libya. Resultantly, there was space for workers from Pakistan who were happy to go to Saudia for good money and the blessing of being in the holy land. I had a chance last year to meet a 75-year-old Pakistani woman in Medina, who was a doctor and had come to the Kingdom during the 1970s to help set up health services. Though she retired a long time ago, her only desire was to spend the last years of her life in Medina.

In any case, Saudi society, dependent on oil revenue and not eager to do labor, was happy to enjoy the presence of this dedicated workforce. An old joke is that one of them was asked to define if love was pleasure or work. They responded that, ‘It must be pleasure because if it were work we would have hired an Indian to do it.’ But it seems that KSA’s prince-king wants to change this by making his people work, and he is in a hurry to do so. Vision 2030 aims to shift the emphasis from oil revenue to developing domestic production capacity, which, in turn, means making them work for their living. This shift has changed everything for the South Asians in the Kingdom.

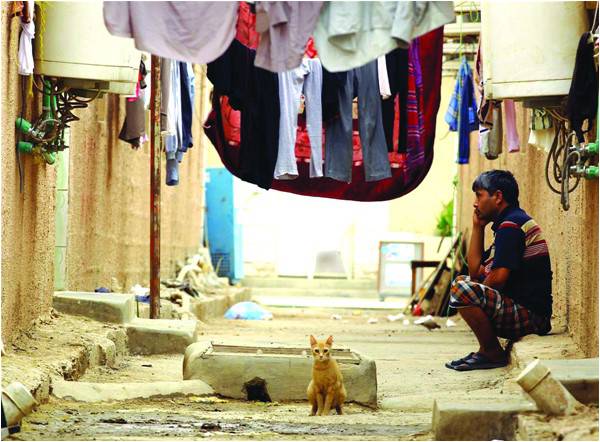

It’s not just the imposition of a tax on a foreign workforce in Saudi Arabia that has made people return but the fact that the overall environment smells and feels different. Restrictions are placed on smaller businesses like telecom kiosks, call centers, grocery stores and others on not hiring non-Saudis or ajnabees at the front desk. The unskilled labor is finding it hard to earn money the way they used to. Today, the gold souk in Jeddah has far fewer shops run by South Asians than before. While the prince-king Muhammad bin Salman, popularly known by the short form of MbS, hopes to modernize society, he has also fueled the frustration of the average Saudi by bringing out the inherent racism against, what may be considered as, weaker races.

In October, for example, a Bengali worker was accidentally run over in Taif by a Saudi driver whose intention was to ridicule a South Asian pedestrian. Naeem Qazi, who had moved to Saudi Arabia during the 1980s, said that running his grocery store had become difficult because even the Arab neighbors had begun to draw a distinction by not shopping there any more. There was a time not too long ago when Qazi ran a shop and a departmental store and had a couple of big American cars to drive. Now with fuel prices going up and newer taxes being added he can only afford to drive one pickup truck and that too not every day. His main concern when he surrendered his iqama (resident permit) was to salvage whatever he could because, as the family discussed between themselves, “Let’s sell when there is still someone to buy our things.”

Most Pakistanis leaving Saudi Arabia believe that in the coming days the situation would get even tougher for expatriates left behind. “The Arabs do not offer a good price for our things because they know it will come to them for free.”

Yet Saudi Arabia feels more of a home than their homeland Pakistan. Naeem Qazi’s daughter Asma constantly complains to her cousins about Pakistan and how things are not so good. The food is expensive and impure and there is lots of corruption. The Saudi riyals they had earned somehow no longer buys them value for money. It was nicer then when they earned in riyals and didn’t care about converting. Asma’s mother complained that: “Here, even the water is not pure – we used to have a good one-time meal in five riyals but this is so much more expensive!” She is not moved even when relatives remind her that her house in Jeddah was smaller than what they have in Pakistan.

Asma, who was born in Pakistan, unlike her two other siblings, had moved to DG Khan in 2015 much before her family after she was married to a cousin. Yet she embraces Saudi culture, wears the abaya, tells off her family if they visit Sufi shrines, and even opposes any celebration for her deceased father-in-law, decrying it as bidaat. She is amazed to see her cousins engaging in bidaat despite being educated. She had stopped a cousin, who had once come to Saudi Arabia for umrah, from touching the shroud of the Holy Ka’aba. She also believes that Pakistan has no morality as women roam around uncovered. When asked what she thought about the change in policy in Saudi Arabia, her response was that it was wrong as many people among her lot and especially in the Kingdom felt that a woman’s respect is in following her man or male members of the family. Asma and her sisters feel flustered at not finding it easy to just walk into a mosque in DG Khan. The younger lot, which moved back to Pakistan in mid-2017, remains nervous about the country of their origin. The brothers and sisters are far more comfortable speaking in Arabic.

The family had never imagined returning to Pakistan. Nasreen’s family had lived in KSA since the early 1950s when her father-in-law migrated. Nasreen’s husband, born in Saudi Arabia, had not sought citizenship. He felt secure as he was a mutawa (member of the religious police), who had received his religious education in the Kingdom. He was even given a residence in Medina where he ran his general store. Forced to come to Pakistan, which is as foreign as any land, Nasreen’s husband struggles with language as Arabic is all he can speak.

Many of these Saudi-Pakistani families believe that their stay in Pakistan is temporary and they will be able to return as soon as MbS realizes his mistake of trying to run the system through an inefficient local population. Even some of their Arab friends, who are probably frustrated with the rapid changes, believe that the new system cannot last and tell these people to hold on until they can return. This may be wishful thinking. However, an unfulfilled desire might also mean that these people could try to create their own Saudi Arabia in Pakistan for which there is a lot of potential. For these migrants, the Najadi culture is all they can relate to with South Asia with its diversity being so hard to imagine.

The writer is an author and independent scholar and can be reached at www.drayeshasiddiqa.com @iamthedrifter

Homeland is equated with origin, which over years has turned into an important category to identify people. But homelands may often not be homes. People can equate lands with home but that can have nothing to do with their origins. They may even be forced to return ‘home’, as in a place of their origin, and yet yearn for the ‘home’ they had to abandon, and in the process never settle down emotionally.

I began to understand the nature of a dichotomous identity when I first met the flamboyant Nadira Naipaul, the wife of V. S. Naipaul, in Bahawalpur during the late 1980s. She was then Nadira Mustafa and lived there with her two children and her then landowner husband, the (late) Iqbal Mustafa, warming the hearts of the town with her presence. When I asked her about the place of origin of her family, I didn’t get an answer that I was used to: My family is from Kenya. She was not African, but that was very much ingrained in her identity.

The decision by Riyadh to impose a tax of about Saudi Riyals 200 on every foreign individual, referred to in Arabic as ajnabi (stranger) has forced hundreds of Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis to send their families home if not return altogether

Hers was one of the many families who were forced to leave their homes to either settle in the West or come to countries associated with their origin. These people were part of the hundreds and thousands of Indians who were taken by the British as professional or unskilled workers to African colonies where they lived and prospered, even setting up their own businesses until Africa started to gain its independence. It was the era of post-2nd World War de-colonization and the emergence of new nation-states and nationalism, in which leaders naturally keeled over towards populism that led them towards a policy of ‘Africanization’. Consequently, Europeans and Indians (that’s how South Asians were generally identified) were evicted. It was a traumatic experience for many, who were forced to leave behind everything they had worked for. Idi Amin, for instance, gave these people, who had British travel documents, the choice to either renounce these documents or leave in 90 days. For those who opted to stay, things didn’t get better either as they were up against discrimination.

While many people migrated to Europe and the Americas, some came to countries carved out of the Subcontinent. Yet there is very little written about them or visualized in art in Pakistan about their personal traumas of that migration. To be fair, not a lot has been written even about the trauma of forced migration of Pakistanis from Bangladesh after 1971. Thus, it is quite probable that public discourse will ignore the evolving tragedy of hundreds and thousands of families currently undergoing (almost) forced eviction from Saudi Arabia. These people are not been given any timeframe to leave but they know it is not longer easy to remain in the Kingdom where they spent decades and invested in a future.

The decision by Riyadh to impose a tax of about Saudi Riyals 200 on every foreign individual, referred to in Arabic as ajnabi (stranger) has forced hundreds of Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis to send their families home if not return altogether. Now it is either men being torn from their families, or making a choice to live in Saudi Arabia legally but struggle to survive in the face of the ‘Saudization’ of the economy as per ‘Vision 2030’ rolled out by the new prince-king.

Reportedly, General (retd) Raheel Sharif tried to give hope to some journalists he had invited from Pakistan at the end of last year to Riyadh. He had indicated that the military coalition would bring numerous benefits to Pakistan, such as the possibility of visa-free entry for member states of the Saudi-funded military coalition. While this may be his understanding, the facts speak otherwise. Saudi Arabia is not keen to import or retain un-skilled labour from Pakistan or other parts of South Asia. In 2017 about 64,689 Pakistanis were evicted from the Kingdom. While many of these people were fairly new migrants who had overstayed their visas or were working illegally, the situation is not good even for those who have lived there longer.

Pakistanis or South Asian Muslims in general have a long association with Saudi Arabia. There were scholars and their families who had settled there during the 1930s and the 1940s. Even today you find houses with the names al-Hindi and al-Sindhi written on the front. Later, as the Saudi state started to evolve with the discovery of crude oil, Pakistani experts played an important role in the evolutionary process. For instance, Pakistani economist Anwar Ali became the head of the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) in 1957, an organization that controls all the resources of the Kingdom and works as its central bank. He remained in the position until 1974. There were many others skilled workers often with an ideological affinity with the Jamaat-e-Islami who worked in various parts of the country.

There was a historically close association between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, which was consciously cultivated by the latter with help from the US and UK. As a result citizenship was conferred on many Pakistanis during the decades of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. However, unlike the British, American or European citizenship, Saudi citizenship cannot be inherited if children do not reside in the Kingdom for a certain period.

A larger tranche of Pakistanis came during the 1970s and later. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto cultivated relations with the Arab Middle East, especially Saudi Arabia and Libya. Resultantly, there was space for workers from Pakistan who were happy to go to Saudia for good money and the blessing of being in the holy land. I had a chance last year to meet a 75-year-old Pakistani woman in Medina, who was a doctor and had come to the Kingdom during the 1970s to help set up health services. Though she retired a long time ago, her only desire was to spend the last years of her life in Medina.

Many of these Saudi-Pakistani families believe that their stay in Pakistan is temporary and they will be able to return as soon as MbS realizes his mistake of trying to run the system through an inefficient local population

In any case, Saudi society, dependent on oil revenue and not eager to do labor, was happy to enjoy the presence of this dedicated workforce. An old joke is that one of them was asked to define if love was pleasure or work. They responded that, ‘It must be pleasure because if it were work we would have hired an Indian to do it.’ But it seems that KSA’s prince-king wants to change this by making his people work, and he is in a hurry to do so. Vision 2030 aims to shift the emphasis from oil revenue to developing domestic production capacity, which, in turn, means making them work for their living. This shift has changed everything for the South Asians in the Kingdom.

It’s not just the imposition of a tax on a foreign workforce in Saudi Arabia that has made people return but the fact that the overall environment smells and feels different. Restrictions are placed on smaller businesses like telecom kiosks, call centers, grocery stores and others on not hiring non-Saudis or ajnabees at the front desk. The unskilled labor is finding it hard to earn money the way they used to. Today, the gold souk in Jeddah has far fewer shops run by South Asians than before. While the prince-king Muhammad bin Salman, popularly known by the short form of MbS, hopes to modernize society, he has also fueled the frustration of the average Saudi by bringing out the inherent racism against, what may be considered as, weaker races.

In October, for example, a Bengali worker was accidentally run over in Taif by a Saudi driver whose intention was to ridicule a South Asian pedestrian. Naeem Qazi, who had moved to Saudi Arabia during the 1980s, said that running his grocery store had become difficult because even the Arab neighbors had begun to draw a distinction by not shopping there any more. There was a time not too long ago when Qazi ran a shop and a departmental store and had a couple of big American cars to drive. Now with fuel prices going up and newer taxes being added he can only afford to drive one pickup truck and that too not every day. His main concern when he surrendered his iqama (resident permit) was to salvage whatever he could because, as the family discussed between themselves, “Let’s sell when there is still someone to buy our things.”

Most Pakistanis leaving Saudi Arabia believe that in the coming days the situation would get even tougher for expatriates left behind. “The Arabs do not offer a good price for our things because they know it will come to them for free.”

Yet Saudi Arabia feels more of a home than their homeland Pakistan. Naeem Qazi’s daughter Asma constantly complains to her cousins about Pakistan and how things are not so good. The food is expensive and impure and there is lots of corruption. The Saudi riyals they had earned somehow no longer buys them value for money. It was nicer then when they earned in riyals and didn’t care about converting. Asma’s mother complained that: “Here, even the water is not pure – we used to have a good one-time meal in five riyals but this is so much more expensive!” She is not moved even when relatives remind her that her house in Jeddah was smaller than what they have in Pakistan.

Asma, who was born in Pakistan, unlike her two other siblings, had moved to DG Khan in 2015 much before her family after she was married to a cousin. Yet she embraces Saudi culture, wears the abaya, tells off her family if they visit Sufi shrines, and even opposes any celebration for her deceased father-in-law, decrying it as bidaat. She is amazed to see her cousins engaging in bidaat despite being educated. She had stopped a cousin, who had once come to Saudi Arabia for umrah, from touching the shroud of the Holy Ka’aba. She also believes that Pakistan has no morality as women roam around uncovered. When asked what she thought about the change in policy in Saudi Arabia, her response was that it was wrong as many people among her lot and especially in the Kingdom felt that a woman’s respect is in following her man or male members of the family. Asma and her sisters feel flustered at not finding it easy to just walk into a mosque in DG Khan. The younger lot, which moved back to Pakistan in mid-2017, remains nervous about the country of their origin. The brothers and sisters are far more comfortable speaking in Arabic.

The family had never imagined returning to Pakistan. Nasreen’s family had lived in KSA since the early 1950s when her father-in-law migrated. Nasreen’s husband, born in Saudi Arabia, had not sought citizenship. He felt secure as he was a mutawa (member of the religious police), who had received his religious education in the Kingdom. He was even given a residence in Medina where he ran his general store. Forced to come to Pakistan, which is as foreign as any land, Nasreen’s husband struggles with language as Arabic is all he can speak.

Many of these Saudi-Pakistani families believe that their stay in Pakistan is temporary and they will be able to return as soon as MbS realizes his mistake of trying to run the system through an inefficient local population. Even some of their Arab friends, who are probably frustrated with the rapid changes, believe that the new system cannot last and tell these people to hold on until they can return. This may be wishful thinking. However, an unfulfilled desire might also mean that these people could try to create their own Saudi Arabia in Pakistan for which there is a lot of potential. For these migrants, the Najadi culture is all they can relate to with South Asia with its diversity being so hard to imagine.

The writer is an author and independent scholar and can be reached at www.drayeshasiddiqa.com @iamthedrifter