Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s New Year message extols the virtues of normalizing relations with India and Afghanistan and benefitting nationally from a significant “peace dividend”. It is also self-evident that without political stability at home, no worthwhile foreign policy or national economic initiative (like CPEC) can succeed. Under the circumstances, Imran Khan’s desperate attempts to derail the elected PMLN government and fledgling democratic system by conspiratorial alliances with rogue elements in the military or by pressurizing the judiciary and election commission of Pakistan to do his bidding are condemnable.

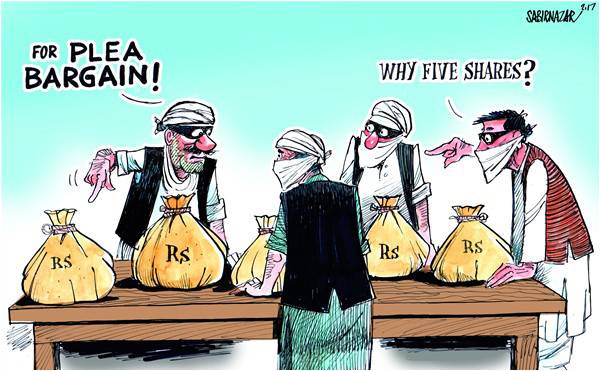

Javed Hashmi’s latest revelations confirm a potent conspiracy between Imran Khan, Tahir ul Qadri, General (retd) Pervez Musharraf and rogue elements among serving and retired military leaders to oust Nawaz Sharif in 2014 by a combination of street agitation and military pressure. The conspiracy failed because Imran Khan wasn’t able to muster sufficient numbers to seize Islamabad and storm parliament. Much the same tactics were tried on the eve of General Raheel Sharif’s retirement last November. But again Imran Khan wasn’t able to mount sufficient force to invade Islamabad and provoke a bloodbath in order to nudge the military into intervening.

The interesting fact is that on both occasions the expected military intervention was aimed not at imposing martial law but at pushing Nawaz Sharif out and calling for early elections, or, failing that, nudging the Supreme Court into a judicial coup to much the same effect, as in Bangladesh many years ago.

The game continues, with one important adjustment. Since the change of high command in the army last month along with significant postings and transfers, the prospects of conspiratorial assistance from those quarters for such nasty objectives has been rendered nil in the short term. Instead, Imran Khan and his fellow conspirators are now focusing almost exclusively on pressurizing the Supreme Court to oust Nawaz Sharif. The arena is Panamaleaks and the target is the new chief justice of Pakistan, Justice Saqib Nisar, and the bench headed by Justice Asif Khosa.

The outgoing Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Anwar Jamali, was threatened with a PTI boycott if he set up a commission of inquiry into Panamaleaks. So he decided to pass the buck to the new chief justice-designate, Justice Saqib Nisar, instead of incurring Imran Khan’s wrath. This put Justice Nisar in front of the firing line. Imran Khan accused him of being Nawaz Sharif’s man, compelling the good judge to clench his fist and thunder in public that he was his own man. But this was a most un-judge-like act because judges are expected to speak through their judgments and not through press releases or public statements. In fact, it actually suggested that the new CJP had come under pressure from Imran Khan and not Nawaz Sharif when he loudly proclaimed his independence. Therefore it was natural that the new CJP would make a new bench without leading it himself.

For one full month, the judges on the old bench asked all manner of questions from the petitioners and respondents but failed to decide certain core issues. Should a commission of inquiry with its own TORs be set up? Should they adopt an adversarial approach (the respondent is innocent until the petitioner proves his allegations) or an inquisitorial one (the petitioner is guilty until he proves himself innocent)? Should they opt for a summary trial or follow due process? In short, should they strictly uphold the law, constitution and due process based on an adversarial trial method or succumb to the popular opposition led by Imran Khan and start an inquisitorial investigation into Nawaz Sharif’s wealth abroad?

Pakistan’s political instability is derived from periodic dismissals of civilian governments and rigged elections. In this evolving polity, army generals have been keen and decisive players, having imposed martial law three times and directly ruled the country for over thirty years with the help of the judiciary to legitimize their rule. In between, the military has indirectly ruled through Presidential allies, proxy politicians and rigged elections. But the Charter of Democracy between Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif in 2006 put paid to these games. The popular movement for the restoration of Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry as CJP SC, followed by PPP-PMLN supported constitutional amendments to make the President a lame duck and strengthen the electoral process, has buttressed the civilian order and diluted the military threat. But it has also shifted the focus of the political opposition to the “independent” judiciary in the last resort.

This does not make for system stability. Political issues must be settled in parliament through free debate and fair general elections at local, provincial and federal levels. Burdening the judiciary thus with explosive political issues subject to popular pressure is doing great disservice to it. Indeed, we can be sure that the Pananaleaks bench of honourable judges will be held to account by history if it succumbs to popular political pressure no less than military force at the altar of law and constitution.

Javed Hashmi’s latest revelations confirm a potent conspiracy between Imran Khan, Tahir ul Qadri, General (retd) Pervez Musharraf and rogue elements among serving and retired military leaders to oust Nawaz Sharif in 2014 by a combination of street agitation and military pressure. The conspiracy failed because Imran Khan wasn’t able to muster sufficient numbers to seize Islamabad and storm parliament. Much the same tactics were tried on the eve of General Raheel Sharif’s retirement last November. But again Imran Khan wasn’t able to mount sufficient force to invade Islamabad and provoke a bloodbath in order to nudge the military into intervening.

The interesting fact is that on both occasions the expected military intervention was aimed not at imposing martial law but at pushing Nawaz Sharif out and calling for early elections, or, failing that, nudging the Supreme Court into a judicial coup to much the same effect, as in Bangladesh many years ago.

The game continues, with one important adjustment. Since the change of high command in the army last month along with significant postings and transfers, the prospects of conspiratorial assistance from those quarters for such nasty objectives has been rendered nil in the short term. Instead, Imran Khan and his fellow conspirators are now focusing almost exclusively on pressurizing the Supreme Court to oust Nawaz Sharif. The arena is Panamaleaks and the target is the new chief justice of Pakistan, Justice Saqib Nisar, and the bench headed by Justice Asif Khosa.

The outgoing Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Anwar Jamali, was threatened with a PTI boycott if he set up a commission of inquiry into Panamaleaks. So he decided to pass the buck to the new chief justice-designate, Justice Saqib Nisar, instead of incurring Imran Khan’s wrath. This put Justice Nisar in front of the firing line. Imran Khan accused him of being Nawaz Sharif’s man, compelling the good judge to clench his fist and thunder in public that he was his own man. But this was a most un-judge-like act because judges are expected to speak through their judgments and not through press releases or public statements. In fact, it actually suggested that the new CJP had come under pressure from Imran Khan and not Nawaz Sharif when he loudly proclaimed his independence. Therefore it was natural that the new CJP would make a new bench without leading it himself.

For one full month, the judges on the old bench asked all manner of questions from the petitioners and respondents but failed to decide certain core issues. Should a commission of inquiry with its own TORs be set up? Should they adopt an adversarial approach (the respondent is innocent until the petitioner proves his allegations) or an inquisitorial one (the petitioner is guilty until he proves himself innocent)? Should they opt for a summary trial or follow due process? In short, should they strictly uphold the law, constitution and due process based on an adversarial trial method or succumb to the popular opposition led by Imran Khan and start an inquisitorial investigation into Nawaz Sharif’s wealth abroad?

Pakistan’s political instability is derived from periodic dismissals of civilian governments and rigged elections. In this evolving polity, army generals have been keen and decisive players, having imposed martial law three times and directly ruled the country for over thirty years with the help of the judiciary to legitimize their rule. In between, the military has indirectly ruled through Presidential allies, proxy politicians and rigged elections. But the Charter of Democracy between Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif in 2006 put paid to these games. The popular movement for the restoration of Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry as CJP SC, followed by PPP-PMLN supported constitutional amendments to make the President a lame duck and strengthen the electoral process, has buttressed the civilian order and diluted the military threat. But it has also shifted the focus of the political opposition to the “independent” judiciary in the last resort.

This does not make for system stability. Political issues must be settled in parliament through free debate and fair general elections at local, provincial and federal levels. Burdening the judiciary thus with explosive political issues subject to popular pressure is doing great disservice to it. Indeed, we can be sure that the Pananaleaks bench of honourable judges will be held to account by history if it succumbs to popular political pressure no less than military force at the altar of law and constitution.