Nawab Akbar Bugti, the Oxford graduate chieftain of the Bugti Tribe, veteran politician and former governor of Balochistan was killed on 26 October 2006 when the cave he was hiding in collapsed 150 miles east of Quetta. Violence and militancy flared up immediately after the death of Akbar Bugti. Balochistan has been in turmoil and crisis since the last military operation against Akbar Bugti on the orders of General Pervez Musharraf. The roots of the Baloch discontent and grievances go back to the time of partition, but the recent flare up in violence and terror has crossed all limits of horror and atrocities.

Security forces were attacked, bridges were blown up, vehicles torched and the most heinous act was the murder of about fifty people just because they belonged to the Punjab province. The unfortunate people of Balochistan have faced terror and bloodshed and many military operations have been launched in the past to control the mayhem, but the problems have persisted and the waves of terrorism will not stop unless and until the root cause is tackled and some negotiated political solution is found to satisfy the Baloch demands.

The problem of Balochistan is, in fact, as old as Pakistan itself. The state of Kalat was an independent Princely state under the British Colonial rule and was initially reluctant to accede to Pakistan. The Khan of Kalat had written to Nehru that he was still considering the idea of remaining independent or acceding to India, but Nehru was not receptive to it, and advised him against such a move. The greater part of Balochistan with Quetta as the capital became part of Pakistan because of the Muslim League’s intense campaign led by politicians such as Qazi Isa under the guidance of Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

The misfortunes of the Baloch province were aggravated with the abolition of the provinces and the formation of the one unit. Punjab, frontier, Sindh and Balochistan were lumped under one unit as the province of West Pakistan with its head quarter in Lahore. Under the presidency of General Ayub Khan, Balochistan was ruled from Lahore by a famous feudal lord: the very fiery, strict and ruthless Amir Mohammed Khan, the Nawab of Kalabagh. Throughout the 1960s, this area remained oppressed and underdeveloped due to a system of governance and a constitution imposed upon the country by a military dictator. In 1969, the Ayub era ended and under Yahiya Khan all the provinces were restored again. Elections were held on the basis of one-man-one-vote in December 1970.

After 1972 under the leadership of ZA Bhutto, the 1973 constitution was framed and promulgated and Balochistan was again accorded full provincial status. Since independence in 1947, Balochistan province has been ruled by Baloch leaders most of the time except during the martial law periods – when the province was under martial law governors. For more than 40 years, Baloch politicians have been in the driving seat of the province and their rule has been weak and reeked of poor governance. They failed their mandate and responsibility to the people who elected them to office.

With the 18th amendment to the constitution in 2010, the province was given more funds for development. The program of Aghaz-e-Haqooq-e-Balochistan provided massive resources for development. Unfortunately the tribal sardars who were favourites of the establishment managed to grab the lion’s share of the funds and used them to enrich themselves and their families. The powerful establishment closed its eyes to the loot and plunder of the Baloch elite to keep the restive province quiet and under control. In spite of lavish allocations of funds the money never reached the poor toiling masses and the province continued to suffer under poverty and mismanagement.

Balochistan is the biggest province of the country in terms of land area, making about one-third of the country with a population of just under twelve million – making it a very sparsely populated region. Baloch political leaders have luxurious houses in Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi and some even in Dubai and London. Baloch leaders hardly ever bother to go out in their constituencies or to interact with the people they claim to represent.

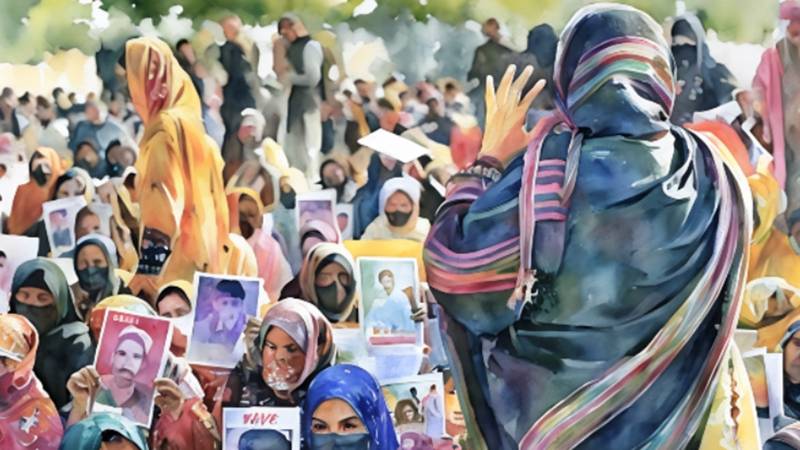

At this stage, the activists of the Baloch Yakjehti Committee are demanding their fundamental rights and it appears that they are the only political force prepared to negotiate within the framework of the 1973 constitution. This makes it all the more important that they be taken seriously by the Powers That Be in the country.

Balochistan is a vast area very rich in oil and mineral resources but mired deep in political discontent and poverty. It appears as if successive governments have failed miserably to address the problem of poverty or to redress the genuine grievances of the people. Force has been used to suppress discontent while at the same time many efforts have been made to attract foreign investment especially in the areas of mineral development and this shows an alarming lack of understanding in the policies of the federal government The benefits of the provincial mineral wealth should go to the common man and not to the sardars or the elite.

The common people of the province are represented by the youngsters protesting on the streets. They want justice and fair trials, an end to forceful disappearances, freedom of speech and association, and access to their rightful share in the economic resources of their land. The old political strategy of divide-and-rule – or getting control of the Sardars and Nawabs – should now end. The ongoing political movement in the province is ample proof that neglecting or suppressing the voice of the people is no longer possible.

The Powers That Be must listen to the voice of the people and remove their grievances – or very soon it may be too late.