This article is the second part of a special three part series. Part 1 can be read here. Part 3 can be accessed here.

Major Consequences of Policies

The policies followed by the military-elites complex, with exploitation of religion as a key instrument, have caused great damage leading to a dysfunctional state, faltering growth, diminished international standing and, last but not the least, to the status of women in the society. Pakistan today suffers from an inner cancer. Let us review these issues.

The Status of Women

Women, who form about 48% of the population, are largely disenfranchised from decision-making at all levels. I have traveled to all continents but nowhere else (except in some parts of the Middle East and Afghanistan) have I have come across such a male dominated society.

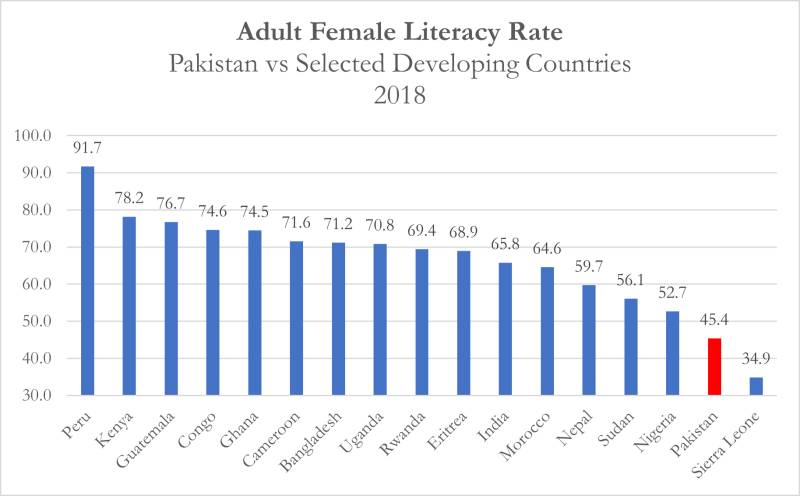

Pakistani females have one of the lowest literacy levels in the developing world. According to the World Development Indicators, female adult (over 15 years of age) literacy rate in Pakistan is lower than even most African countries – e.g., lower than that Ghana and Congo – as shown in the chart.

In 2018, only 10% of women in Pakistan used mobile internet compared to 31% of women in Kenya and 18% of women in Tanzania.

Growth Without Development

In a 2001 World Bank case study, William Easterly labeled Pakistan's political economy as a paradox of growth without development. Even this growth has faltered during the last 25 years as compared to most of Asia. This begs the question: what went wrong?

There is little recognition in Pakistan that as globalization swept across the world after the fall of the Berlin Wall, countries like India, China, and Bangladesh seized the opportunities offered by trade liberalization and progressed, but Pakistan’s ruling elites continued to view the world through a Cold War mindset and thought foreign aid would continue to enable Pakistan to extract geo-strategic rents, if not from the U.S. then from China.

What we are witnessing now is not due to some “policy missteps” in the last 10-15 years or so; it is the consequence of wrong policies pursued over decades. To attribute the current situation to a few decisions or politicians is a disservice to Pakistan's public discourse on the fundamental reasons for the failures.

Diminished Geostrategic Importance

Pakistan’s recent efforts to resume the IMF’s 2019 program have involved the toughest negotiations in its history. The differences between China and Western economies over how to provide debt relief to developing countries in debt distress have also contributed to unprecedented delays to secure bailouts.

Gone are the days when the United States would quietly use its influence to help Pakistan. Pakistan did approach the United States after failing to get concessions from the IMF but it did not help much.

Pakistan’s Army Chief and his senior commanders still sit atop the real power structure.

Pakistan's diminished geostrategic importance has further complicated the situation. American interest in Pakistan since the end of the Cold War was episodic and transactional. America's quest to dominate the Middle East and its rivalry with the former Soviet Union was largely driven by the need to ensure the uninterrupted flow of oil to America and its allies. The United States imported 20.3% of its oil from the Arabia Gulf countries as recently as 2012, a percentage that dropped to 8.2% in 2021. With the growth of non-fossil energy sources, the discovery of large oil and natural gas deposits outside the Persian Gulf, and increased domestic U.S. oil and natural gas production, the Middle East's vast energy resources have become of declining strategic significance to the United States.

The Dysfunctional State

I wrote in 2012, in the preface of my book, Balkanization and Political Economy of Pakistan, that:

“The US failure in Afghanistan could result in a civil war in Afghanistan. Such an outcome is borne out of its apparent unwillingness to accept her failure or defeat and inability, for whatever reason, to arrive at a political settlement and prepare for an orderly transition according to a plan acceptable to all the major parties. These developments have far-reaching and grim implications for Pakistan’s future, but its ruling elites seem to be paralyzed by the traumatic experiences of the past decade. They hope to muddle through this period with the help of friends like China and Saudi Arabia. Historically, they treated Washington as the center of the world, India as their main rival, and accumulating wealth as the main goal. In the future, the US may not bail out Pakistan as it did during the Afghan war and the War on Terror. India sees China as a rival and merely considers Pakistan an irritant that has the potential to destabilize the whole area. The country has an acute leadership crisis and its fragile democracy - or, more accurately, a plutocracy - governs only in theory. The army still calls the shots but the state has never been so weak.”

Since 2012, a lot has changed in Pakistan, but for the worse.

Pakistan’s Army Chief and his senior commanders still sit atop the real power structure. Decades of quasi-army rule, the ‘jihad against the Soviets, and the War of Terror saw an unchecked and extraordinary rise in the influence and power of the intelligence agencies who practically control Pakistan’s broken and predatory institutions, all while reporting to the army’s high command.

Besides a rise in militancy, sectarian and ethnic extremism, and proliferation of arms, the use of militant and non-militant groups by the intelligence agencies has a less obvious and ominous dark side: the rapid growth of the ‘black economy” fueled by the growing power of property mafias and criminalization of the society. The rule of law, governance, and civilian institutions are the major casualties of this phenomenon.

The Faltering Growth

We are going through more than an economic meltdown. We are witnessing the failure of the state at all levels. Hence, economists or technocrats who ignore or do not understand the background of this failure are unlikely to make a meaningful contribution to the conversations about Pakistan’s way forward, if any. To put Pakistan’s failure in the

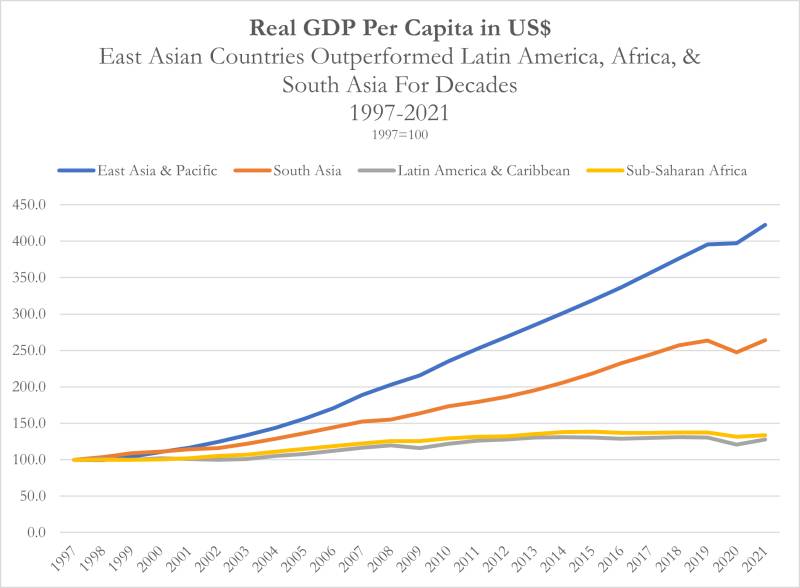

During the 25 years from 1997 to 2021, the real per capita income of the developing countries in East Asia and the Pacific (excluding those of high-income countries like Japan and Australia) more than quadrupled and grew at an annual average of 6.2%. The Asia-Pacific region remained an attractive investment destination even during 2020 – when Covid19 hit the globe - accounting for 53.6% of global Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). East Asia and Southeast Asia were the largest recipients in the region, attracting roughly 80% of Asia’s inward FDI.

Developing countries in Latin America and Africa grew their per capita incomes at a much smaller rate of around 1 %. Latin America was a poor place in 1980. Its gross domestic product per person amounted to only 42% of that of the average citizen of the so-called Group of Seven rich nations that then ruled the roost. And last year, Latin America’s domestic product per person amounted to 29% of that of the G7 nations, according to Bloomberg.

The economic output of the average citizen of Africa declined from 17% to 10% of that of the average citizen of the rich world over those 42 years, measured at purchasing power parity.

It is therefore not surprising that Latin American and African countries are among the largest borrowers from the IMF. In March 2023, twenty borrowers accounted for 82% of the total IMF lending of around $150 billion. The top 20 borrowers were in Latin America or Africa except for Ukraine, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Pakistan is the fifth largest borrower. The last time India needed the IMF’s help was in 1991, Korea and the Philippines in 1998, and Indonesia in 2000. Is IMF the problem or Pakistan’s own policies?

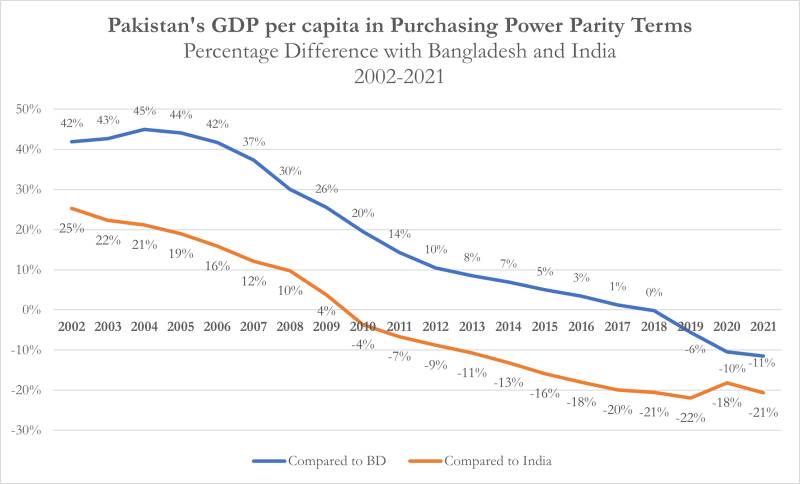

This chart shows the dramatic rise in the per capita incomes (Purchasing Power Parity Terms) in Bangladesh and India compared to Pakistan whose per capita income was 60 % higher than Bangladesh's and 47% higher than India's in 1997. Just in 13 years, that is in 2010, Pakistan's per capita turned lower than that of India and the gap with Bangladesh was reduced to just 20 % from 60% in 1997.

In 2021, Pakistan’s real per capita income was 11.5% lower than that of Bangladesh and 21 % lower than that of India. During the 25 years, Pakistan's GDP growth lagged behind its two neighbors by more than 2.5 percentage points per year. This is not a small difference because it has a huge impact over the long term on the overall size of the economy and standard of living.

| 20 Years Growth Rates | ||

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | Population | |

| Bangladesh | 6.19% | 1.23% |

| India | 6.19% | 1.31% |

| Pakistan | 4.22% | 1.85% |

Even if Pakistan’s population had grown at the same rate as that of Bangladesh, its GDP per capita would have been only 3.9 % higher ($5,438) than it was in 2021 ($5,232) but still lower than Bangladesh’s $5,911.

While a higher population growth rate is a significant concern, it is the widening gap between Pakistan’s economic growth rate and that of the rest of developing Asia that poses the greatest challenge to the state, military, politicians, and the people of Pakistan.

China’s one child policy was not what brought down China’s fertility rate as is commonly believed. Stefan Dercon, professor of economic policy at the University of Oxford, maintains (Gambling On Development, 2020) that “China’s fertility rate fell in response to better health and education and greater access to it – in short, broader development.”

The Human Development Index (HDI) developed by Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq is a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development, such as a long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living. According to a UNDP report, only Pakistan (161st position) and Afghanistan (180th position) are in the low human development category among South Asian countries, while Bhutan (127), Bangladesh (129), India (132), and Nepal (143) are in the medium human development category.

While a higher population growth rate is a significant concern, it is the widening gap between Pakistan’s economic growth rate and that of the rest of developing Asia that poses the greatest challenge to the state, military, politicians, and the people of Pakistan. Can we transform a national security-focused (often a client) and inward-looking state with a hugely young but relatively unskilled population into a growth economy that can compete internationally?

The Inner Cancer

In an article published by Karachi’s Newsline magazine in May 1992, I wrote:

“Now faced with the fundamental changes in power structures, political parties have two choices: either they play the role of junior partners or give a new and original program to the masses. This is a historic opportunity. Will Pakistan become a battleground for xenophobic ethnicism, religious fundamentalism, and eco-medievalism or will the secular and democratic forces be able to prevent the explosion this combustible convergence of forces may cause if not in 1992 then perhaps in 2001.”

Ayub Khan believed that Pakistan had, indeed, the same traditions as Prussia. The cancer of militarism spread in Pakistan, from the “we are like the Prussians” complex of General Ayub, to the insatiable appetite for the army budget (to which all civilian prime ministers also pandered), to the equally insatiable appetite of the military hierarchy for sheer power for the sake of power; first the appetite of the top generals for political power and later the appetite of the colonels and majors for administrative power in every detail all the way down from state-owned corporations to local authority.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto made many mistakes but he was one of the most brilliant statesmen of his times, if not the most intelligent as Henry Kissinger once described him. The establishment must pay attention to what Bhutto wrote in his book,” If I am Assassinated.”

“Engulfed by the revolutions of Europe, the Prussian Junkers expanded their standing army. In due course, the Prussian Army had expanded beyond the resources of Prussia. It was evident that the size and capacity of Prussia would not be able to bear the burden for long. The situation became so untenable, that it was said: “Prussia is an army with a country and not a country with an army.”

The Prussia Junkers were well aware of the consequences. Three choices stood before them. Either:

(a) Prussia had to expand to become the pivot of the German fatherland; or

(b) The large standing army had to be reduced; or

(c) Prussia would collapse under the weight of the large standing army.”

Pakistan is sinking under the weight of its once omnipotent and omnipresent military complex. It has run the country like a centralized state: from hand-picking prime ministers to manipulating elections, from starting wars to conducting covert cross border operations, from rewriting the constitution to dictating judges, from running large businesses to directing local governments, and so on.

Is there a Way Forward?

The establishment has toyed with the idea of bringing in ‘technocrats’ to fix what it perceives to be just an economic crisis. Economic commentators generally describe Pakistan’s troubles in terms of its chronic twin deficits: recurring current account deficits and fiscal deficits. Pakistan’s number one issue is the intellectual bankruptcy and short-sightedness of its military, political, business, and land-owning elites. The intellectual crisis has been exacerbated due to systemic suppression of freedoms, abysmal quality of education, and steady brain drain over the decades.

Corruption is another issue in Pakistan, but it needs to be viewed in a wider context. The public discourse in Pakistan tends to oversimplify issues.

One of the biggest problems in Pakistan is the misguided policies that are sometimes produced under the influence of a toxic combination of ignorance and arrogance, leading to unintended consequences. One such example is Afghanistan. Despite supporting the Taliban for almost two decades, celebrating their return to power in August 2021 as an instance of “breaking the chains of slavery”, in former prime minister Imran Khan’s words, Pakistan now finds itself diplomatically isolated internationally, with little leverage even with Afghanistan and has been unable to stop terrorist attacks from militants based in Afghanistan.

Corruption is another issue in Pakistan, but it needs to be viewed in a wider context. The public discourse in Pakistan tends to oversimplify issues. “Remove corruption and everything will be fine” is a common refrain. High post-1990 rates of GDP growth in China have been clearly compatible with high levels of corruption. Transparency International (2017) puts China, with a score of 40, in the 79th place among 176 compared countries. Other East Asian countries with a relatively high incidence of corruption (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan) have also experienced high growth rates. In 2021, India was put in the 80th place among 180 compared countries but Pakistan was 140th.

The corruption mantra has also been used to divert attention from far more bigger issues and what may be described as legal and institutionalized corruption.

Pakistan’s military spending is among the top ten globally, in terms of percentage of the GDP. Its tax-to-GDP ratio of around 9% is among the lowest in the world. It has to borrow more every year because there is no money left in the budget to spend on development after servicing debts and military spending.

According to a United Nations Development Program (UNDP) report, the military establishment owns the largest conglomerate of business entities in Pakistan, besides being the country’s biggest urban real estate developer and manager, with wide-ranging involvement in the construction of public projects.

Some political activists call Pakistan “plotistan” alluding to the fact that buying and selling plots of land is the most lucrative business in Pakistan due to an extremely favorable tax regime that has the support of the military establishment. No wonder that around 80% of household wealth is concentrated in the property sector.

This article is the second part of a special three part series. Part 1 can be read here. Part 3 can be accessed here.