The federal government has handed the country's premier intelligence and security agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), keys to a mass surveillance system set up at the telecom operator level in the country, empowering its officers to "intercept calls and messages" and to trace calls made through any telecommunication system.

The government made the designation through an act that circumvents the Parliament by issuing a Statutory Regulatory Order (SRO) through the Gazette of Pakistan (the official permanent record for all such notifications).

SRO 1005(I)/2024 for the Ministry of Information Technology And Telecommunication (Digital Pakistan) under Section 54 of the Pakistan Telecommunication (Re-organization) Act 1996, "in the interest of national security and apprehension of any offence."

It empowered the ISI to nominate officials who are at least basic pay scale (BPS) grade 18 to intercept calls and messages.

The notification comes over a week after Justice Babar Sattar of the Islamabad High Court, while hearing a case on alleged illegal interception of telephonic communication between former first lady Bushra (Imran) Bibi and former federal minister for overseas Pakistanis and human resources Zulfiqar Bukhari and the subsequent leak to the public of such an intercepted call.

The case

In his 28-page order issued on June 29, 2024, Justice Sattar noted that he had repeatedly asked the federal government and its various security and telecommunication organs whether the Constitution or statutory law empowers the executive to record or surveil phone calls or other telecommunication between private citizens. If it does, what is the supervisory and regulatory legal regime within which such recording and surveillance can take place and if no legal provision exists to tap phones or record telecommunications, which public authority or agency can be held liable for such actions?

However, Justice Sattar lamented that neither the federal government nor any of its divisions or agencies assisted the court in answering this critical question.

"This Court has repeatedly implored the learned counsels for the Respondents and the learned Additional Attorney General to ensure that the respondents discharge their obligations to address the questions framed for adjudication in a candid and truthful manner."

When the court asked the Additional Attorney General (AAG) if rules had been framed under Section 54 of the Telecom Act (the same act under which ISI has been empowered to use lawful surveillance and interception apparatus), the AAG "made a feeble attempt to argue that the matter should be heard in the chambers as it might have implications for national security."

"National security, however, is not the security of an inanimate monolith. It is the collective security of the citizens to be protected by the state. In a democracy, the state can conceivably not articulate interests that are independent of and divorced from the interests of the citizens," the order read, adding, "The notion of national security is therefore used as a broad concept to define, promote and protect the collective interests and rights of the citizens of the state, and not those of any artificial legal construct that can be set up against the collective rights and interests of the citizens."

Where national security interests trump the individual interests of the citizens, it is by virtue of a shared understanding that in a community, the collective rights and interests of the community will be granted preference over the rights and interests of any individual. It is for this purpose that individual rights, as guaranteed by the Constitution, are often balanced against the collective rights and interests of society, including in cases where the national security interests of the polity are at stake.

"The petitioners before the court are private citizens. The conversations that have been recorded and leaked to social media have nothing to do with national security," the court said, adding, "The entire purpose of rule of law is, on the one hand, to put citizens on notice as to the rules that they must abide by in ordering their lives, and on the other, to put state functionaries on notice as to the manner in which they are permitted to exercise state authority that has been conferred upon them by law, which is to be exercised as a public trust."

In a rule-of-law polity functioning under a written Constitution and declared laws, it is inconceivable that public functionaries may be permitted to act pursuant to secret policies not backed by the law and the Constitution, especially when such policies affect citizens' fundamental rights.

Extent of state surveillance

In its order, the court clarified the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority's (PTA) disclosures about the mass surveillance equipment installed in the country.

The court was informed that PTA required telecom operators to install the sweeping mass surveillance system, Lawful Intercept Management System (LIMS), at the expense of telecom licensees at Surveillance Centres designated by the PTA, for use by the designated agencies, through which over 4 million citizens (or around 2% of all subscribers) could be actively surveilled simultaneously at any given time, whilst providing designated agencies access to the audio and video data of citizens through the networks of telecom licensees.

"Such mass surveillance system seems inspired by George Orwell's '1984'," the court observed.

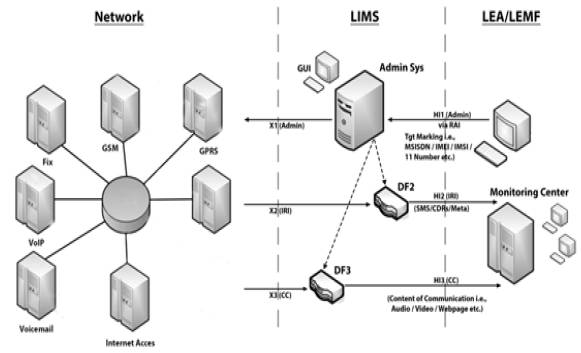

Providing details of the LIMS, the court was informed it enables interception of data and records of telecom customers. The manner in which interception can be undertaken by designated agencies for purposes of surveillance through the LIMS at the Surveillance Center was explained through the following chart:

15.

The system includes a "Law Enforcement Monitoring Function" that allows designated agencies from the Surveillance Centre to initiate a 'track and trace' request through the click of a button in relation to any SIM (Subscriber Information Module), IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity) number, or MSISBN (Mobile Station International Subscriber Directory Number) identity belonging to a consumer.

Once the 'track and trace' request has been initiated, the request goes through the LIMS in an automated manner, which is then connected to the network of telecom licensees. This process continues without requiring any human intervention to retrieve details of any short messages (SMS), call data reports, and metadata reported through a server into a monitoring centre established at the Surveillance Centre.

Similarly, through another server, the entire content of communication between consumers undertaken through the network of the telecom licensee, including his/her audio and video content generated on their device or which passes through their device, and records of web pages browsed are shared with the monitoring centre at the Surveillance Centre. This data can be reviewed and stored.

The court was informed that through LIMS, data of any consumer could be surveilled and retrieved, while voice calls could be heard and reheard and SMS read. The system is powerful enough that any encrypted material (created through the use of mobile apps, etc.) forms part of the consumer data; the encrypted material is also shared with the monitoring centre at the Surveillance Centre. While LIMS does not provide automated means to decrypt such encrypted data, but requests for decryption can be made to the relevant company that owns the social media application.

The court was informed that PTA had obligated telecom licensees to ensure that up to 2% of their consumer base could be surveilled through LIMS at any given point. The court was also informed that the telecom licensees had no visibility over which consumer was/is being surveyed or what track and trace requests have been initiated by designated agencies utilising the LIMS. The court was informed that the LIMS had been procured, installed and deployed on the directions of PTA at the Surveillance Centre identified by PTA and can be used by designated agencies whose identity was not revealed to the court.

The court termed the LIMS a mass surveillance system through which 2% of all telecom consumers in Pakistan can be surveyed without any judicial or executive oversight. It added that the installation of this system under the direction of the PTA appeared to have no legal backing.

"Neither any rules have been framed for purposes of lawful interception nor any permission has been granted by the federal government," the court noted, adding, "The court has been informed that no permission has been granted for purposes of surveillance under Section 5 of the Telegraph Act. The court has also been informed over the last 11 years since the enactment of the Fair Trial Act, not one surveillance permission has been sought from the courts in accordance with the provisions of the Fair Trial Act."

However, the court noted that reports stating that no warrants for surveillance had been sought from the courts under the Fair Trial Act, which is the only existing legal framework for undertaking surveillance of citizens, together with reports stating that no agency or entity has been granted authorisation to undertake surveillance under any other law, including the Telecom Act and the Telegraph Act, leads to one of two possibilities:

- The state and its investigation and intelligence agencies have never felt the need to undertake surveillance for any state purpose. Or,

- That state agencies and instrumentalities undertake surveillance illegally without being backed by the authority of law

The court noted there are surveillance mechanisms in place through the use of which audio recordings of Prime Ministers (irrespective of the political party he is affiliated with), political leaders in and out of Parliament, judges and their relatives, and relatives of politically relevant individuals and prominent businessmen are being made and subsequently released through the anonymous accounts on social media, which conversations then make their way to mainstream media.

The court said a suggestion was sheepishly made by the AAG that audio recordings, as part of illegal surveillance, may have been the handiwork of hostile agencies operating in Pakistan.

But when the AAG was asked whether it would not constitute a massive security breach and failure on the part of the state if the conversations of the country's highest executive, legislative, and judicial officeholders could be surveilled by hostile agencies, the AAG did not press the point any further.

"The LIMS has been installed and is being operated without any backing of the law, and those who are using and/or enabling the use of the LIMS to surveil citizens may have rendered themselves liable to criminal liability under provisions of the Fair Trial Act, Telecom Act, Pakistan Electronic Media Crimes Act (PECA), Telegraph Act and Pakistan Penal Code," the court observed.

The federal government and intelligence agencies expressed their inability to identify who was undertaking illegal surveillance in Pakistan and how the fruit of such surveillance in the form of audio leaks finds its way to social media and mainstream media in Pakistan.

The court, however, observed that the federal government is liable for the installation of LIMS and the simultaneous mass surveillance of over 4 million citizens under the direction and supervision of the state.

"The Prime Minister and the members of his cabinet are individually and collectively responsible for the existence and operation of any mass surveillance system if it turns out that such surveillance is being or has been undertaken," the court had observed.