Henry Kissinger who died on November 29 2023 aged 100 is generally reckoned to be one of the most effective public officials produced by the United States in the 20th century. While he undoubtedly had a huge impact on a range of matters that bedevilled US relations with the outside world – between the US, China and the USSR (Russia), Vietnam, the Arab-Israel conflict, US and Latin America – to name only the most prominent issues that concerned international security in the 1960s and 1970s, his legacy today is, however, highly controversial. While no one – not even his opponents - questions his intellectual ability his ethical failings were many and are unconcealable. His unabashed commitment to realpolitik in the service of his adopted country in which there was no room for moral constraints has left behind a trail of destruction in Vietnam and many other parts of the world.

The incantation that ends justify the means is often evoked by the powerful when they wish to inflict disproportionate punishment on the less powerful for their real or imaginary transgressions or, more usually, simply for defying them. However, historical judgments can and, indeed, should be less forgiving. And, in terms of history Kissinger is unlikely to be forgiven, not only for the trail of death and destruction that he had a hand in causing but also for effectively legitimising and, indeed, fortifying the unedifying amorality in international relations that has allowed questions of justice and fairness in international disputes to fall by the wayside. He was by no means solely responsible for this but international relations over the years, far from being based on any sense of right and wrong are, in fact, more in the grip of lies and casuistry than before. The tragedies of Palestine and Kashmir, of course, immediately come to mind in this regard, never mind the Rohingyas and countless others whose voices have been drowned out in the mire of ‘realism’ in international relations.

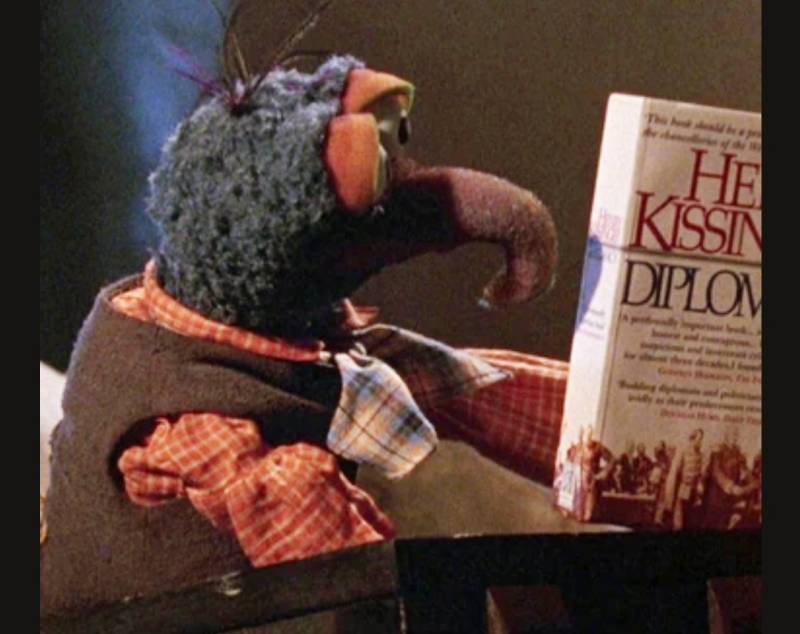

For the purpose of historical analysis much can be gleaned from the early lives of public officials to understand their beliefs and conduct in later years. In Kissinger’s case he was only 15 when his family left Germany in 1938 and made its way to the US. He thus witnessed at first hand the human suffering and destruction that World War II had caused across Europe and Asia, including the use of nuclear weapons by the US in Japan. Looking back at European history, especially the relatively peaceful 19th century that began with Napolean’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815 and ended with the start of World War I in 1914, the young Kissinger developed a strong interest in the power of diplomacy and statesmanship to prevent conflict between nations. After World War II he put his scholarship to analysing relations between Germany and its neighbours in the 19th century and the contribution that individuals like Castlereagh and Metternich had made in the preservation of peace and, hence, in indirectly facilitating the industrialisation of France, Germany and Britain in that period. His PhD dissertation at Harvard entitled Peace, Legitimacy and Equilibrium: A Study of the Statesmanship of Castlereagh and Metternich is a tour de force combining detailed knowledge of events with uncompromising analytical rigour. At 383 pages long it resulted in his alma mater, Harvard, setting out the “Kissinger rule” limiting student dissertations to half that length.

What his dissertation and, indeed, his other writings, reveal is the belief that problems between nations can be resolved by powerful individuals winning over the other side by the strength of their advocacy and not necessarily through the application of notions of justice and fairness or of what is right. The over-riding objective, according to Kissinger, was to prevent war. Short of that, the diplomatic modus vivendi should be restricted to maximising your gains and minimising your losses through debate and discussion; in other words, relations between nations should be like market transactions whether between friends or between friends and foes.

Kissinger at that stage of his life was the classic 19th century European scholar conditioned to live within the framework known as the ‘balance of power’ rather than being subject to any notions of justice and fairness. Following Harvard, the young Kissinger found his niche in the relatively unsophisticated but powerful United States of America confronting the less powerful but increasingly assertive USSR, both playing out their rivalry in a cold instead of a hot war. And his talents would not go unrecognised even though he spoke English like a German. Starting a professional career as an academic at Harvard he soon found, however, that his ambitions would be better served in a political environment.

At first, Kissinger was happy to serve rising political personalities, such as Nelson Rockefeller, in a back office capacity. But in 1968 he threw himself full time into Richard Nixon’s Presidential campaign – in his opinion the more likely winner - and after his win over Hubert Humphrey Nixon rewarded Kissinger with the post of National Security Advisor in 1969. But, within a few months, the ambitious Kissinger was running US foreign policy eclipsing the then Secretary of State Will Rogers. In so doing, almost single-handedly he initiated a paradigm shift in US foreign policy at the strategic level. It was in this capacity that Kissinger began to grapple with the imbroglio of the Vietnam war, the cold war with the USSR and political and social unrest in many parts of the world. In 1970/71, responding to overtures from Mao ze-Dong and Chou en-Lai, which had been conveyed to the Americans through Pakistan, Kissinger shocked the world by secretly travelling to Beijing from Islamabad in July 1971 to start the process of rapprochement with the People’s Republic of China.

The visit to Beijing set in train the normalisation of ties with China and in 1972 Nixon made him Secretary of State. Full normalisation involving the exchange of Ambassadors only happened in 1978 but in 1972 Taiwan lost its membership of the UN. The absurd farce of the Nationalist Government in Taiwan representing the whole of China in the UN was thus ended by the stroke of Kissinger’s pen. Here, it is worth recalling that while the Nationalist Government had been in control of the whole of China since 1918 and during the war between 1945 and 1949, after 1st October 1949 the Nationalists had lost control over the mainland. It is also important to remember that Taiwan historically had always been a part of China, except between 1895 and 1945 when it was a Japanese colony. To imagine that the Nationalists could represent the whole of China had been not only been absurd in itself and legally specious but did incalculable harm to the reputation of the US and, indeed, all others who supported the US in votes on the issue in the General Assembly.

Such self-serving behaviour had been typical of pre-Kissinger US pique over such issues and its childish desire to bend reality to its will. It probably doomed the UN to becoming a debating society instead of becoming an international institution capable of resolving problems between its members, as had been envisioned at the time of its establishment. Kissinger ended this silly charade, at least partially. The new US-China relationship was then enshrined in the Shanghai Communique of 1972 which said that “the US formally acknowledged that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain that there is but one China”. This is the achievement that Kissinger is justly famous for.

Normalisation of relations between the US and China then led to mutual overtures by both the US and USSR during 1972-1975 and a more substantive détente between the two and to arms reduction talks such as SALT I and SALT II. The signing of the Helsinki agreement for the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) also followed. Gradually, the risk of a major confrontation between the US and USSR declined. However, proxy wars in Africa became the new arenas for US-USSR rivalry and the US, despite protests from its own black citizens, continued to support, along with much of Western Europe, the abominable scandal of apartheid in South Africa. The extent of this insanity in South Africa can be gauged by the fact that, in partnership with Israel, it had even embarked on a programme to make nuclear weapons, with the US and Europe largely looking on.

So, what then can one make of Kissinger? He was certainly not a run of the mill Secretary of State and when he joined the Nixon Administration in 1969 the US was heavily involved in one of its ‘forever’ wars in Vietnam. He certainly made it his number one priority to end US involvement and perhaps in his judgment normalising relations with China would be a necessary pre-condition to this end it. If so, Kissinger was mistaken. The war actually carried on for five more years, including the barbarous bombing of Cambodia and Laos that Kissinger kept secret not only from the world but from his own country too.

Today, it has to be remembered that despite Kissinger’s efforts the Vietnam war ended not on US terms or in some messy, unworkable compromise but in a humiliating military defeat for the US. So, while he can be credited with normalising relations with China his efforts with respect to ending US involvement in Vietnam were at best marginal.

Nonetheless he was happy to accept the Nobel prize for peace along with Le Duc Tho, the Foreign Minister of North Viet Nam, who declined it. The thawing of the cold war with the USSR happened in fits and starts and here, too, while the process set in train via the OSCE played its part, it was USSRs Mikhael Gorbachev who made it real on the ground.

Kissinger’s contributions in the realm of foreign policy in other areas were similarly peripheral. For example, the US did not stop interfering in Latin America. It was involved in the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Allende in Chile in 1973. His intervention in the overthrow of Allende showed that he was, in the end, not even a believer in realpolitik but an old-fashioned hegemonist for whom coups and assassinations were probably no more than inconvenient details. Likewise, Kissinger was unable to have any long-term impact in the Middle East beyond helping in the cease fire after the Yom Kippur war in 1973. The Israel-Palestine conflict not only continues to this day but has now acquired a level of violence which suggests that a tragedy of monumental proportions is on the cards in that region of the world in the not-too-distant future. Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy in 1973 enabled a cease fire but made no substantive headway and changed no minds in Israel about its long-term future.

From Pakistan’s perspective the outside world has concluded that Kissinger should be held responsible for atrocities carried out by the Pakistan Army in 1971 in the then East Pakistan. Realistically speaking, however, Kissinger’s ability to influence the course of events in East Pakistan remains an open question. It does seem plausible that he decided to ignore events in the then East Pakistan in view of Pakistan’s usefulness in the process of normalising US-China relations. His own writings do not shed much light on this. His culpability in the eventual emergence of Bangladesh with the critical help of India, however, is not in the same category as his culpability in the bombing of Cambodia and Laos where he himself personally authorised much, if not all, the devastation that the US visited upon the two hapless countries.

Finally, given all this, how will Kissinger be remembered, say, in 50 years? While he was feted round the world as an elder statesman and was a prolific and scholarly author who wrote on a wide range of subjects he will be remembered primarily, if not solely, for his breakthrough in the US rapprochement with China 1971, for which the Chinese also acknowledge his role. He was not only exceptionally knowledgeable about China but understood that country with sympathy and clarity that are unmatched today, both in the US and Europe.

However, today no one in the US has any time for thinking strategically about the future. Existential issues such as global warming are given short shrift and the US has all but embarked on a new cold war, this time with China. Given that disturbing reality it suggests that his influence on the conduct of US foreign policy was no more than peripheral. Disasters in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere amply show that the US continues to behave and act like a hegemon, unable to learn any lessons from its growing list of failures. Looking at the state of the world today it is not only the US but also its principal client state Israel that should heed the early lessons from Kissinger, the European scholar of history, and not the hegemon, and find a fair and viable route for its long-term survival.