As Pakistan turns 70, the cry for “change” becomes ever more shrill and violent. On the surface, it is an angry rally for an end to “corruption” because everyone – young and old, male or female, rich or poor, Sindhi or Punjabi, Shia or Sunni, religious or secular, urban or rural – is morally and politically outraged by it. But the underlying reality of the country is more unsettling. Far from the prospect of a “Pakistani spring” on the wings of the latest troika of judiciary, military and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, the “awakening” portends a deepening of the crisis with fearful longer term consequences. Consider.

A British Council survey three years ago indicated the direction of “change” in Pakistan. The country is increasingly “young” and “urban”. Half its citizens are under 20 and over 65 percent are under 30. The population has trebled in fifty years. Another 14 million youth will be eligible to vote in 2018.

Over 94 percent of the youth think the country is headed in the “wrong” direction. Over 80 per cent think their economic position will not improve. Across all divides, pessimism is the defining trait of this next generation “youth bulge”. Violence stalks everyday life. Over 70 percent think life is not safer for Pakistanis compared to the past – Pakistan ranks 149th of 158 countries in the Global Peace Index.

The survey reveals that the greatest source of anxiety for the youth is not terrorism but insecurity of jobs and justice and economic inflation. Only 10 per cent have full time contracted employment.

The report notes that approval rates are lowest for political parties and parliaments. Other institutions – religious, media, military and judiciary – have high approval rates. Less than 30 percent think “democracy” can deliver development and employment whereas nearly 70 percent think military rule and shariah can be better solutions. Nearly 70 percent are conservative/religious. A majority of those with mobile phone access to social media are politicised and want to vote because they think they can “change” the system. Significantly, over 8o percent of countries in which over 60 percent of the population is under 30 years of age like Pakistan are prone to violence and civil conflict because the “system” isn’t delivering expectations of social and economic well-being.

This raises the question of whether forced “regime change” for reasons of selective party-political “corruption” can stem the tide of insecurity, violence and pessimism in the body politic of Pakistan. The empirical evidence suggests that corruption has not declined despite recurring “regime change” of “corrupt governments” in the last seventy years of independent Pakistan. In fact, corruption has not abated despite alternating civil-democratic and military-dictatorship rule in the country. Indeed, regime change in the current circumstances based on the aspirations and reactions of the religious-conservative youth bulge that favours military-judiciary rule will sound the death knell of Pakistan.

The “Arab Spring” in the Middle East is a good yardstick by which to measure the nature of “change” prompted by the youth bulge. Instead of delivering a dividend in the form of a democratic system that spurred economic growth, security and stability, one after the other the countries of the ME succumbed to dictatorship, anarchy, religious civil war, foreign intervention and state breakdown, transforming the anticipated “Spring” into a “Winter of discontent”. Given the social and political propensities of the youth bulge in Pakistan, this route for change will destroy Pakistan too.

Nearly 15 million youngsters, most of whom are conservative, unemployed and angry, will be added to the voting list in 2018. If they veer to the religio-fascist right at the instigation of unelected state institutions whose own record of delivering jobs or justice is abysmal, the country will inch closer to renewed violence, instability and separatism. But if they are accommodated within the “corrupt” democratic system, Pakistan still has a chance of reinventing a new democracy that is better able to cope with the demands for state security and economic welfare.

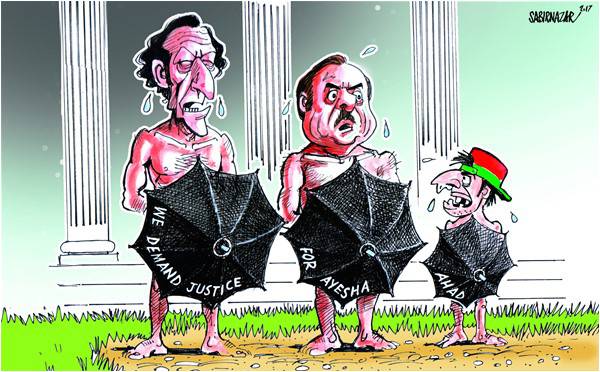

It is, of course, true that political parties and their dynastic leaders are no less culpable for the dysfunctional state of Pakistan’s economy and democracy than military coup-makers and their judicial legitmizers. However, what is interesting in the current quagmire is the political contest between an old party of the conservative-right that was midwifed by the military and judiciary but is now shifting to the centre and trying to become autonomous of both state institutions and a new party of the same leanings and origins that is swinging further right on the basis of the youth bulge and dependence on the same state institutions.

Under the circumstances, the current political crisis that is pegged to “corruption” and regime change is actually about the direction in which Pakistan is headed in a contest between imperfectly democratic, centrist but corrupt political regimes and equally corrupt but violent, religio-fascist autocracies that are a recipe for anarchy and state breakdown as in the Middle East. n

A British Council survey three years ago indicated the direction of “change” in Pakistan. The country is increasingly “young” and “urban”. Half its citizens are under 20 and over 65 percent are under 30. The population has trebled in fifty years. Another 14 million youth will be eligible to vote in 2018.

Over 94 percent of the youth think the country is headed in the “wrong” direction. Over 80 per cent think their economic position will not improve. Across all divides, pessimism is the defining trait of this next generation “youth bulge”. Violence stalks everyday life. Over 70 percent think life is not safer for Pakistanis compared to the past – Pakistan ranks 149th of 158 countries in the Global Peace Index.

The survey reveals that the greatest source of anxiety for the youth is not terrorism but insecurity of jobs and justice and economic inflation. Only 10 per cent have full time contracted employment.

The report notes that approval rates are lowest for political parties and parliaments. Other institutions – religious, media, military and judiciary – have high approval rates. Less than 30 percent think “democracy” can deliver development and employment whereas nearly 70 percent think military rule and shariah can be better solutions. Nearly 70 percent are conservative/religious. A majority of those with mobile phone access to social media are politicised and want to vote because they think they can “change” the system. Significantly, over 8o percent of countries in which over 60 percent of the population is under 30 years of age like Pakistan are prone to violence and civil conflict because the “system” isn’t delivering expectations of social and economic well-being.

This raises the question of whether forced “regime change” for reasons of selective party-political “corruption” can stem the tide of insecurity, violence and pessimism in the body politic of Pakistan. The empirical evidence suggests that corruption has not declined despite recurring “regime change” of “corrupt governments” in the last seventy years of independent Pakistan. In fact, corruption has not abated despite alternating civil-democratic and military-dictatorship rule in the country. Indeed, regime change in the current circumstances based on the aspirations and reactions of the religious-conservative youth bulge that favours military-judiciary rule will sound the death knell of Pakistan.

The “Arab Spring” in the Middle East is a good yardstick by which to measure the nature of “change” prompted by the youth bulge. Instead of delivering a dividend in the form of a democratic system that spurred economic growth, security and stability, one after the other the countries of the ME succumbed to dictatorship, anarchy, religious civil war, foreign intervention and state breakdown, transforming the anticipated “Spring” into a “Winter of discontent”. Given the social and political propensities of the youth bulge in Pakistan, this route for change will destroy Pakistan too.

Nearly 15 million youngsters, most of whom are conservative, unemployed and angry, will be added to the voting list in 2018. If they veer to the religio-fascist right at the instigation of unelected state institutions whose own record of delivering jobs or justice is abysmal, the country will inch closer to renewed violence, instability and separatism. But if they are accommodated within the “corrupt” democratic system, Pakistan still has a chance of reinventing a new democracy that is better able to cope with the demands for state security and economic welfare.

It is, of course, true that political parties and their dynastic leaders are no less culpable for the dysfunctional state of Pakistan’s economy and democracy than military coup-makers and their judicial legitmizers. However, what is interesting in the current quagmire is the political contest between an old party of the conservative-right that was midwifed by the military and judiciary but is now shifting to the centre and trying to become autonomous of both state institutions and a new party of the same leanings and origins that is swinging further right on the basis of the youth bulge and dependence on the same state institutions.

Under the circumstances, the current political crisis that is pegged to “corruption” and regime change is actually about the direction in which Pakistan is headed in a contest between imperfectly democratic, centrist but corrupt political regimes and equally corrupt but violent, religio-fascist autocracies that are a recipe for anarchy and state breakdown as in the Middle East. n