The first half of October brings two important global events: International Children's Palliative Care Day and World Hospice and Palliative Care Day, both focused on raising awareness about the essential role of palliative care and advocating for better services worldwide, for both children and adults.

In Pakistan, the need for paediatric palliative care is critical. With nearly 80 million children suffering from life-threatening or life-limiting illnesses, a survival rate of paediatric cancer below 50%, and a high burden of life-limiting inherited disorders, the healthcare system remains devoid of dedicated paediatric palliative care services.

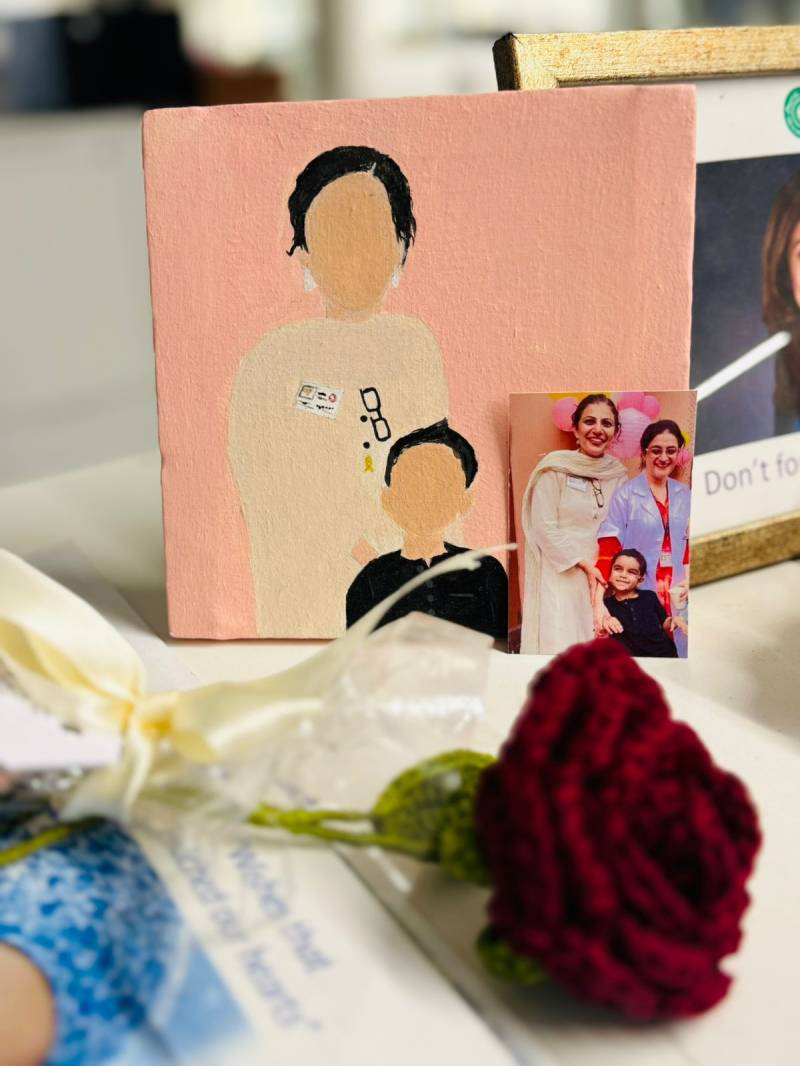

This piece celebrates Dr Shahzadi Resham, a pioneer in this field. As a Paediatric Palliative Care doctor at Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH), she established Pakistan’s first-ever Paediatric Palliative Care service. Her early contributions to paediatric oncology have earned her the prestigious 2024 Young SIOP Rising Star Award.

Through my interview and her profile, I aim to bring attention to the critical role palliative care plays in healthcare.

***

Wajiha Anwar: Can you share what inspired you to specialise in paediatric palliative care?

Shahzadi Resham: Paediatric palliative care is about providing holistic support to children with life-threatening or life-limiting conditions and their families. It's not just about managing medical symptoms, but also addressing emotional, social, and spiritual challenges. Our focus is on improving the child’s quality of life and supporting the family through the illness and even after the child passes, especially during the first years of bereavement.

My journey into paediatric palliative care began during my fellowship in paediatric haematology-oncology. I met my mentor, Dr Sadaf Altaf, who encouraged me to pioneer this field in Pakistan. Initially, I had planned to pursue paediatric oncology and had interviewed for positions at different hospitals. However, after reflecting on Dr Altaf's advice and realising the unmet need for paediatric palliative care in the country, I took on the challenge. In 2018, I started working as a general paediatrician, at AKUH, with a commitment to establish the first paediatric palliative care service in Pakistan.

WA: What personal experiences or moments led you to this field?

SR: When I began, I had no prior understanding of paediatric palliative care. However, through my experiences with patients and my empathetic nature, I became increasingly drawn to it. The more I connected with the families, the stronger my commitment grew. Over time, the fulfilment of helping others became my main source of motivation. While it wasn’t initially my goal, the advice from my mentor inspired me to take on this challenge and fully dedicate myself to the field of paediatric palliative care.

As a certified paediatric bioethicist, I often face conflicts of interest, particularly when communicating with children about their diagnoses and impending death. In Pakistan, cultural norms lead parents and children to protect each other from painful truths, resulting in missed opportunities for connection

WA: Since paediatric palliative care is a relatively new field in Pakistan, could you share your journey of becoming a qualified paediatric palliative care provider and how you established this service at your institution?

SR: In 2018, I started as a general paediatrician with the goal of becoming a paediatric palliative care physician. To advance in this field, I researched training options and began shadowing Dr Atif Waqar, who had launched Adult Palliative Care services at Agha Khan University. Under his mentorship, I gained experience in paediatric palliative care consultations and gradually started practicing independently.

Understanding the importance of formal training, I began preparing for the USMLE while continuing my work. We discovered a fellowship opportunity at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Despite delays caused by COVID-19, I stayed committed, securing certifications and being promoted to assistant professor in 2020. I also assumed a leadership role with the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) to advocate for education in lower-middle-income countries.

After passing the exams, I started my fellowship at St. Jude in September 2021. Now, I am the only clinically trained paediatric palliative care physician in the Eastern Mediterranean region, with extensive experience in patient care, education, and leadership.

WA: What were the key milestones in the development of this service?

SR: Since returning from my fellowship in October 2022, I have been working as a paediatric palliative care physician and helped launch the Quality of Life Service at Agha Khan University Hospital. Though still in its early stages, the service has made significant progress over the past year and a half, gaining recognition both within the hospital and nationally.

Currently, I am the only physician on the team, managing multiple roles such as social worker, coordinator, and nurse, though efforts are underway to hire additional staff to meet the service’s unique demands. The adult palliative care team provides ongoing support, sharing resources like nurses and psychologists. This collaborative approach aligns with international best practices, where paediatric palliative care services often develop with guidance from adult palliative care programs.

WA: Can you talk about the initial reactions from the medical community and the public?

SR: I was encouraged by my family to pursue advanced treatments like bone marrow transplants, which are innovative but prohibitively expensive for most people in Pakistan, costing around 5 to 6 million rupees. Instead, my focus has always been on helping patients live fulfilling lives and pass away with dignity, pain-free. My parents fully supported my choice to enter paediatric palliative care, and my mentor and her husband, whom I consider spiritual parents, along with several colleagues and my uncles in the U.S., provided essential support throughout my journey, despite their concerns about the challenges of starting such a service in Pakistan.

Within the medical community, a significant challenge is the lack of awareness around holistic patient care. The focus often remains solely on medication, overlooking the broader emotional and psychological aspects of therapy. Many view my work with sympathy, often questioning how I manage the emotional toll, but I consider it a privilege to be involved in the lives of extraordinary children and their families, helping to ease their pain and improve their quality of life.

As doctors, we are trained to cure, but we sometimes forget the importance of caring. Shifting from ‘cure’ to ‘care’ is especially important when treating life-threatening illnesses. Families don’t expect miracles; they just want us to be there for them. This shift in approach can be difficult for the medical community to grasp. However, the response from patients and their families has been overwhelmingly positive, and even small gestures like casual conversations help create a safe space for them to express their feelings, which continues to drive my passion for this work.

WA: What are some of the biggest obstacles you are facing in setting up these services?

SR: First, the external challenges. During my fellowship, I conducted research on paediatric care providers' attitudes and knowledge, particularly in cancer care. The study highlighted the need for better education, training, access to pain management, home care resources, funding, and advocacy. Upon returning to Pakistan, I encountered a medical community that often misunderstood paediatric palliative care, associating it solely with end-of-life care, leading to misconceptions about my role. Moreover, limited educational opportunities and resources in Pakistan, alongside cultural stigmas around palliative care, further complicate its acceptance and integration.

Now for the personal challenges. The emotional toll of dealing with end-of-life cases can lead to burnout, and after losing a patient, it often takes me a few days to recover. To cope, I have developed self-care strategies that include photography, exercise, meditation, journaling, and weekly therapy sessions. These help me balance the emotional demands of my work while maintaining personal boundaries, allowing me to continue providing care effectively.

WA: Can you share some success stories or moments that reaffirmed your commitment to this work?

SR: Every day in paediatric palliative care brings small yet meaningful victories, even if it's a simple smile or a heartfelt message from families or colleagues. A memorable moment was when I arranged for a terminally ill patient to attend a PSL cricket match with his friends. He later sent a video of his joyful experience, and although he passed away a month later, that memory was cherished by his family and me.

I also find fulfilment in the appreciation I receive from medical students and colleagues. For instance, a resident once highlighted my approach to shared decision-making and empathy during a difficult conversation with a patient's family, and presented it as an example to the entire team, which felt like a personal victory and truly brightened my day.

WA: What are your hopes and plans for the future of paediatric palliative care in the country?

SR: My future plans are focused on three levels. First, at the institutional level, I aim to build capacity, expand services, and raise awareness about paediatric palliative care among healthcare providers, emphasising that it is a human right, not a privilege. This includes engaging the government and the wider medical community.

Second, despite resource limitations, I plan to train healthcare providers through rotations, enabling them to integrate palliative care into their own institutions. Key elements like communication, listening, and family-centred care will be prioritised. I also engage in memory-making activities with families, such as creating keepsakes, which, though initially emotional, later bring comfort.

Finally, at the international level, I find it noteworthy that we gained global recognition for our efforts even before establishing solid foundations at the national level. I see the importance of integrating paediatric palliative care into Pakistan's healthcare system for sustainability and policy-making. I would advocate for this integration at a governmental level, ensuring these services are recognised as a right for patients and families.

WA: What advice would you give to someone considering a career in paediatric palliative care?

SR: Entering the field of paediatric palliative care requires careful consideration and a genuine desire to pursue this challenging path, as it is not suited for everyone. It's important to understand the motivations behind someone’s interest in this area. A passion for the work is essential for survival and success in this demanding role. While there will undoubtedly be challenges, the rewards are significant. I am more than willing to offer guidance and support to those interested in this fulfilling yet complex profession.

WA: How has your work in this field shaped your views on life, death, and the healthcare system?

SR: Doctors regularly encounter life-and-death situations, deepening my appreciation for each day. This perspective motivates me to enhance the quality of life for my patients and their families, whether through small moments like sharing smiles or facilitating comfort in their care environment. Witnessing death has reinforced my commitment to providing the best care possible, focusing not just on saving lives but on easing their experiences and ensuring comfort in their final moments.

WA: Is there anything else you'd like to share about your journey or the importance of paediatric palliative care?

SR: I want to address the ethical challenges in palliative care, which balances factual ethics with a patient- and family-centred approach. As a certified paediatric bioethicist, I often face conflicts of interest, particularly when communicating with children about their diagnoses and impending death. In Pakistan, cultural norms lead parents and children to protect each other from painful truths, resulting in missed opportunities for connection.

I strive to facilitate more open family conversations, emphasising that awareness of the benefits of honest communication is essential. Many families may later regret not discussing these issues, which could have enriched their time together.

The most fulfilling aspect of paediatric palliative care is its focus on compassionate care. I teach my medical students that true compassion involves sharing in the suffering of patients and families, being present during crucial moments like death for both their closure and mine.

Ultimately, I believe that paediatric palliative care is a fundamental human right that should be accessible to everyone. However, in resource-limited countries like Pakistan, we must start integrating this care into our medical services to meet the needs of those facing life-threatening and life-limiting illnesses.