Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author, and do not represent The Friday Times' editorial position. We invite our readers and contributors to send us commentaries on this subject.

This article calls for establishing a government of experts, drawn from different fields, and the imposition of a national emergency for the next ten years. I am simply recommending the establishment seek expert advice and help – just as a person should contact a doctor when they are sick. I know this is probably a somewhat unpopular and unusual proposal, but it is worth thinking through, given our historic failures. Foreign leaders and governments already deal directly with the Army Chief, as he is seen as the principal decision-maker and no one else commands much credibility.

Pakistan’s situation is dire. The country, with the world’s fifth largest population, is Asia’s sick man and on life support, composed of short-term foreign loans and deposits. A combustible combination of demographics, debt, and rising poverty levels might lead to a collapse, if not in 2024, then perhaps in 2029, on a scale Pakistan has never experienced.

In May 1992, I wrote (in Newsline Magazine) about what the failure of democratic forces to provide an agenda of change could lead to: “will Pakistan become a battleground for xenophobic ethnicism, religious fundamentalism, and eco-medievalism or will the secular and democratic forces be able to prevent the explosion that this combustible convergence of forces may cause, if not in 1992, then perhaps in 2001.”

The country’s ruling elites are going around foreign capitals, begging bowl in tow. A section of the population sees Imran Khan as their savior. I can only offer them my sympathies, because he too is a product of the experiments that have been conducted on Pakistan.

The temporary improvement in economic indicators is deceptive. Pakistan has about $8 billion in foreign exchange reserves, funded by deposits of around $8 billion from China, $5 billion from Saudi Arabia, and $2 billion from the United Arab Emirates. The country is insolvent.

The country’s ruling elites are going around foreign capitals, begging bowl in tow. A section of the population sees Imran Khan as their savior. I can only offer them my sympathies, because he too is a product of the experiments that have been conducted on Pakistan, and failed – among other reasons - due to his ineptitude and delusional level of arrogance, which was not backed by intellect or experience.

It is wrong to assert that Pakistan’s current problems started in 2016. Nawaz Sharif’s model of building infrastructure using foreign debt was the principal cause of the 2018 external debt crisis. The PML-N government simply benefitted from a collapse in oil prices in 2014-15, and which stayed low till 2020. The PML-N government projected CPEC as a game-changer following an economic model that failed in Ethiopia and elsewhere.

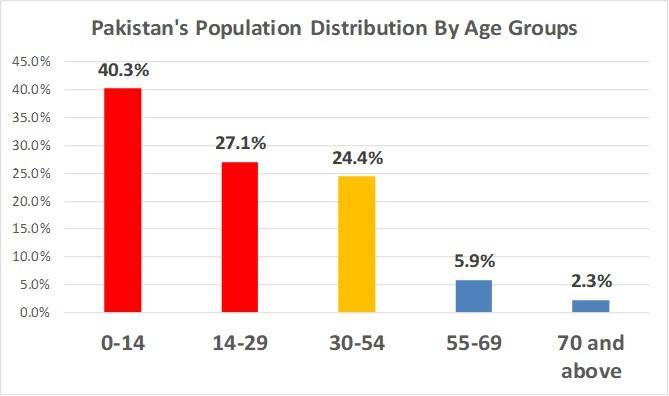

Nearly 67% of Pakistanis are 29 years old or younger. Only a handful of elite schools and colleges offer quality education. Present-day Pakistan is an intellectual wasteland. Most of today’s widely held views on Pakistani history – propagated most recently through social media - are greatly distorted and starkly contrast with the realities of the present and past.

Generations have grown up believing false narratives so much so that even many of Pakistan’s best-educated doctors, engineers, teachers, bankers, economists, generals, and politicians demonstrate only a shallow understanding of Pakistan’s existential crises. A recent case study on Pakistan prepared at the Harvard Business School exemplifies this problem.

I do believe that at this point in history, it would be wise to accept that we do not have a functional democracy and the establishment is in the driving seat. It has been since 1977. The periodic and ad-hoc nature of the military interventions has made the country’s crises even worse.

It is easy and mostly correct to blame the establishment for the pitiful state of the political parties, but the politicians have been too eager to share the crumbs of power rather than stand for democratic principles. This is not a new and recent development. Politics is broken because the politicians made so many compromises over the years that there are now very few who genuinely stand for a democratic order.

The failure of the political parties is tragic. If they have become less relevant, then this calls for serious introspection. However, the country has to be governed and the economy must be saved to help the millions who cannot wait for a stable political order to emerge organically, because they have waited for over 76 years and neither have political freedoms nor economic development to show for their patience.

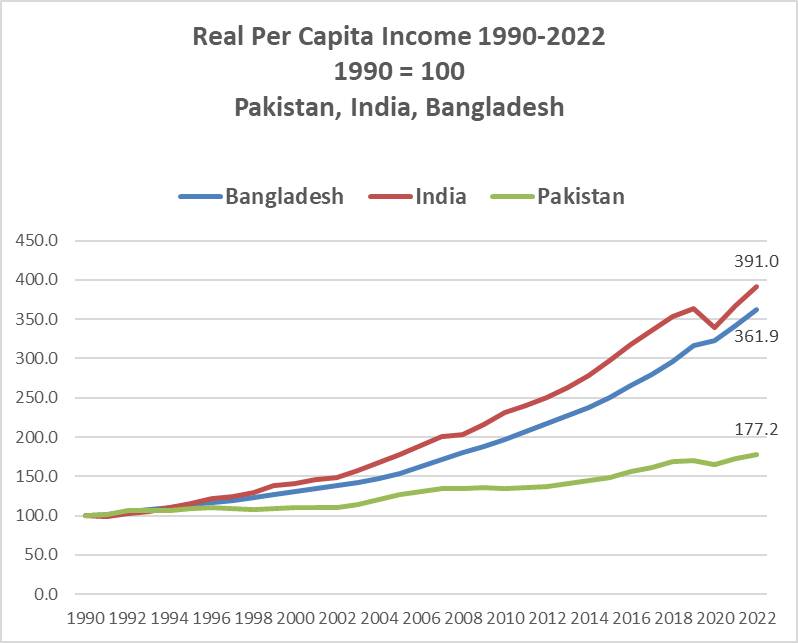

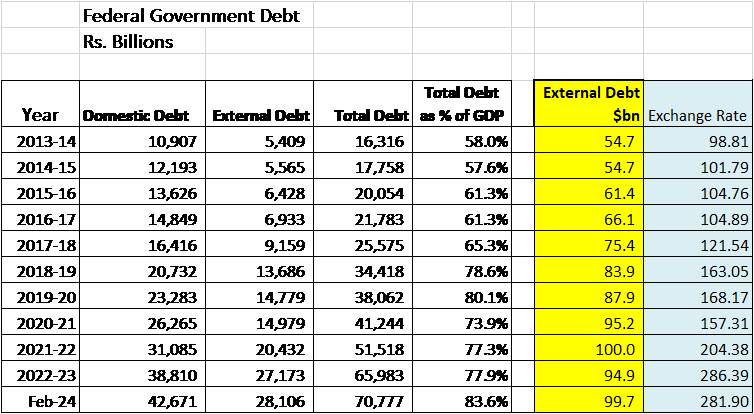

Source: author

This graph shows the huge cost of not introducing reforms since the 1990s. This cost escalated dramatically in the recent year due to gross mismanagement of the economy, first under the PTI, and then under PDM with Ishaq Dar as finance minister.

It is easy and mostly correct to blame the establishment for the pitiful state of the political parties, but the politicians have been too eager to share the crumbs of power rather than stand for democratic principles.

Pakistan has suffered greatly due to the hybrid form of government. The establishment co-opted the political elites and governance became a perpetual game of musical chairs. Economic development took a backseat. Hence, the vast majority of the country’s people are poor, uneducated, backward, and ill-equipped to compete with other nations. Why would global corporations invest here if they can’t find skilled and trained people?

Political parties suffer from pervasive mediocrity, cronyism, and sycophancy. The establishment recruited people who didn’t know much about governance or economics. The cycle of ineptitude has been vicious. But the time is running out fast for any remedies to work effectively.

Only the establishment can correct its own course

Hence, there is an urgent need and a compelling case to institutionalize the role of the armed forces in formal governance. Their covert role has made problems even worse. The political parties and their leaders simply don’t have the capacity to face the challenges, partly because only the mediocre and pliable were “selected” over decades to run the country, but this model has failed.

An obvious question is why don’t I suggest that the army stop interfering in politics and let the politicians do their job? I wish it was as simple as many pundits seem to suggest on television or through their opinion pieces in newspapers. They should come out of their ivory tower and be honest.

Pakistan has suffered greatly due to the hybrid form of government. The establishment co-opted the political elites and governance became a perpetual game of musical chairs. Economic development took a backseat.

The vast majority of the current generation of political leaders are not products of democratic struggle. They rely on the military to get elected and stay in power. They do not have any incentive to serve the people or focus on economic development.

No one will invest in Pakistan until the establishment commits to a reform program. The Constitution should be amended to allow for the Armed Services Chiefs to be members of the federal cabinet for the duration of their tenures in office. The requirement for ministers to be members of Parliament and Assemblies should be removed. Pakistan has thousands of well-qualified and talented professionals abroad. We must harness this great resource. Hence, all restrictions on dual nationals holding public office should be removed if they were born in Pakistan.

These measures are necessary to induct competent people and experts into the government and bureaucracy. There is nobody else who can do it - except the establishment. It should embrace reform for the sake of its own future if not that of millions of stunted and malnourished children.

The time is now

Steven Dercon, professor of economic policy at the University of Oxford, recently published an opinion piece in Dawn and advised Pakistan’s rulers to use the current crisis as an opportunity for economic reform. “Given Pakistan’s daunting and urgent challenges, there is perhaps no alternative”, he warned.

The Constitution should be amended to allow for the Armed Services Chiefs to be members of the federal cabinet for the duration of their tenures in office.

The ideological debate in Pakistan, if there is one, tends to oversimplify the issues with liberal use of jargon such as democracy and dictatorship, neoliberalism and socialism. Capitalism played a critical role in making America the richest and most powerful country in the world. Admittedly, there is not just one market model. There are striking differences between the Japanese version of the market system and the German, Swedish, and American versions.

Democracy and institutional development are part, not drivers, of development

China and South Korea chose the path of state-directed growth despite the differences in their political systems. It is wise to remember the reasoning – associated with among others, the Indian Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen – that the question of whether democracy encourages or retards development is part of a false distinction. Democracy and institutional development are part of the development and so are not to be judged as drivers of it.

Historically, Japan followed a slow but steady course toward a democratic culture and initiated Asia’s first modernization program. South Korea and Taiwan followed an authoritarian route for decades after the Second World War, before moving towards democratization in the 1980s.

China has been a one-party state, but so has North Korea. Hence, it is difficult to argue whether democracy or authoritarianism alone can explain Japan’s remarkable success or China’s miracle.

Ha-Joon Chang, a Korean economist at Cambridge University, is a leading advocate of state-led development but even he accepts that “both democracy and markets are fundamental building blocks but we need to balance them.”

Yuen Yuen Ang, a leading expert on China, maintains that there is no one-size-fits-all right model for development. Particular solutions for market promotion vary over the course of development, within countries, and even within the locales of a single country.

Joseph Stiglitz says “globalization has also brought huge benefits – East Asia’s success was based on globalization, especially on trade opportunities, and increased access to markets and technology.”

Good governance and inclusive institutions have become popular buzzwords following the publication of the influential book Why Nations Fail authored by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson.

However, Oxford’s Stefan Dercon has termed it as a “deeply pessimistic agenda for change or how change may be supported if history is to blame: countries appear to be told to buy yourself a better history.”

The myth of democratic and inclusive institutions as a condition for development

China, South Korea, Taiwan and more recently Indonesia and Bangladesh did not have inclusive political and economic institutions when they started their reform programs.

Korea was widely criticized for promoting the ‘crony capitalism’ of chaebols. China, after the destruction wreaked by the Cultural Revolution, hardly had strong institutions to deliver the kind of take-off it achieved post-1979.

In Pakistan, we cannot wish the establishment away. The political process is broken and the parties are a joke. We need to find a way forward. There is no perfect recipe for development or guarantees in life.

Across the world, a near-miss political or economic crisis has often been the spark for actions to promote growth: it happens when governing elites sense there is no other option but to reform, such as India in 1991.

Each country must chart its course tailored to its unique circumstances. In Pakistan, we cannot wish the establishment away. The political process is broken and the parties are a joke. We need to find a way forward. There is no perfect recipe for development or guarantees in life.

The real and practical choice

The hybrid setup is doomed to fail. The real choice is between an incompetent and ineffective establishment-backed government, versus a competent and effective establishment-backed government. That is the choice we have, because we have not had a completely democratic government even after General Zia-ul-Haq died in 1988.

Some pundits' answer to every problem is political stability and civilian supremacy. We may have to wait 30-40 years to have it. What do we do now however, will determine what the country looks like in the near future.

Pakistan has two ticking bombs: demographics and debt

Hence, there’s a case for an emergency rule for the next 10 years. We must focus completely on economic development under a government of experts led by the establishment.

50% of the population is 19 or below 19, about 50% of the population is functionally illiterate, 40% of school-age children are out of school, the median age is 19, and the poverty rate is at least 40%. This is an explosive mix. It should be abundantly clear that we don't have much time.

Many Pakistani colonial institutions – the military and civil bureaucracy, and judiciary - have evolved into self-perpetuating elite institutions that resist change and seek to maintain the status quo. Over the years, they co-opted politicians, religious leaders, the landed gentry and also large industrial conglomerates, and together, they have neither pursued inclusive economic growth nor a liberal, tolerant society.

Millions of our children drink contaminated water, breathe toxic air, are undernourished and stunted, and have no access to quality education.

As a British economist Stefan Dercon wrote recently, one-in-15 children now die in Pakistan before the age of five, double the rate in India, Nepal, or Bangladesh; almost half the children below five have a lower than healthy height for their age.

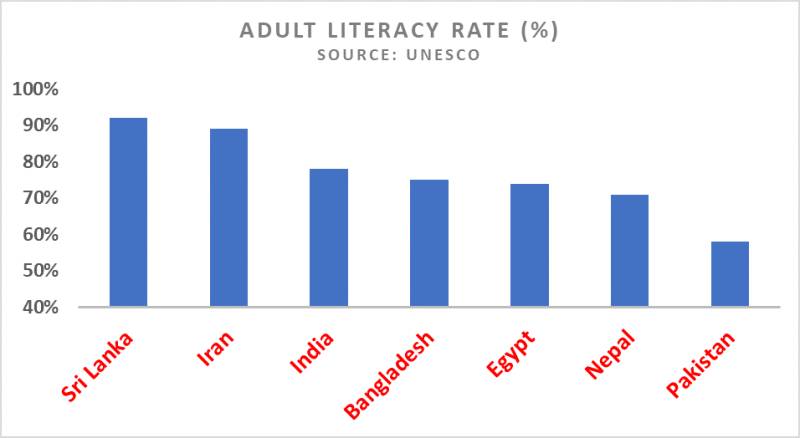

Pakistan's literacy rate is among the lowest in the world

The functional literacy rate is even worse. 26 million children are out of school. Even Nigeria’s numbers look better.

It has a population of 215 million and has around 10.5 million out-of-school children.

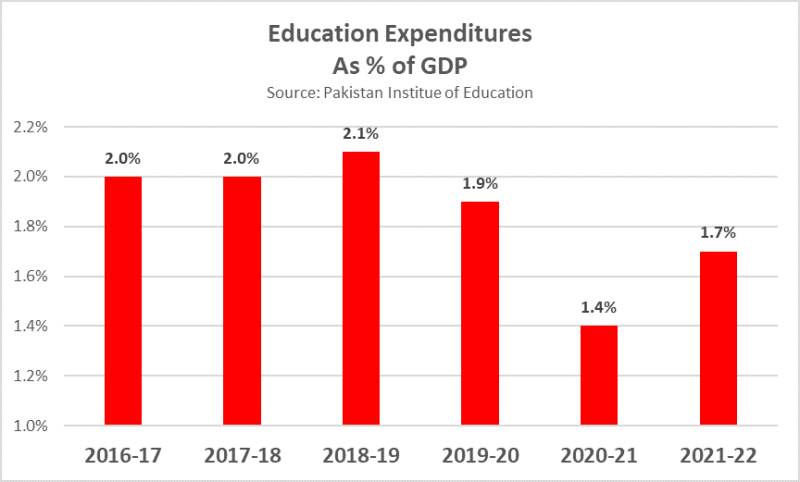

The country’s spending on education is going down in real terms

Pakistan government (public) debt has doubled every 5 years since 2014

Pakistan’s total public debt is over Rs70 trillion now or around 80% of the GDP. Its build-up has accelerated in the last 5 years. If the current level is not reduced, more stress will likely follow.

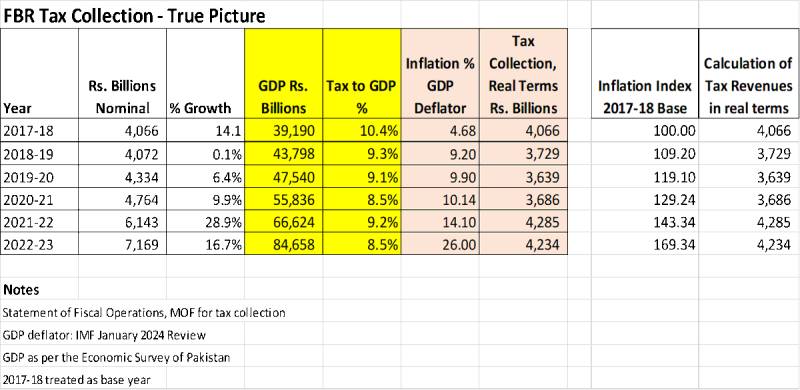

Pakistan has a chronic resource problem

Pakistan has failed for decades to improve its tax collection, but tax revenues have stagnated in real terms in the last five years. They went down during 2018-2021, both in real terms, as well as a proportion of the GDP.

This table tells the real story; not told by the mainstream media. This is the cost of the ineptitude and selfishness of elites. Pakistan drowning in debt.

Outdated Colonial Governance Model

We have an outdated governance structure. Many Pakistani colonial institutions – the military and civil bureaucracy, and judiciary - have evolved into self-perpetuating elite institutions that resist change and seek to maintain the status quo. Over the years, they co-opted politicians, religious leaders, the landed gentry and also large industrial conglomerates, and together, they have neither pursued inclusive economic growth nor a liberal, tolerant society. Resultantly, Pakistan is falling behind all its peer nations in South Asia in income and human development.

Regressive Exploitation of Religion

These powerful elites exploited religion to perpetuate power and the so-called “Islamization” of everything from domestic to foreign policy, has not been constructive or progressive, but regressive, even destructive; thereby obstructing the country's modernization and progress.

It will depend on the policies of the ruling elites whether Pakistan will end up like Afghanistan, Iran, Egypt, or North Korea, or whether it will make progress like South Korea, Indonesia, or Malaysia have. These nations rebuilt their countries from the ruins of armed conflicts and civil wars that they experienced during and after the colonial era.

Deregulate, Devolve, Deradicalize and Digitize

Pakistan needs a charter of national revival, based on a 4D strategy: Deregulate, Devolve, Deradicalize and Digitize.

Deradicalization is a prerequisite to having a modern and tolerant society open to doing business with the world. Deregulation is essential to harness the energies of the private sector severely constrained by bureaucratic hurdles and rent-seeking.

Without the devolution of powers to local governments, it is impossible to provide basic services in a country with one of the fastest urbanisation rates, and without digitalization, Pakistan cannot compete in a world driven by knowledge capital and increasingly defined by the digital divide. Pakistan’s future will be defined by its success or failure to meet these challenges.