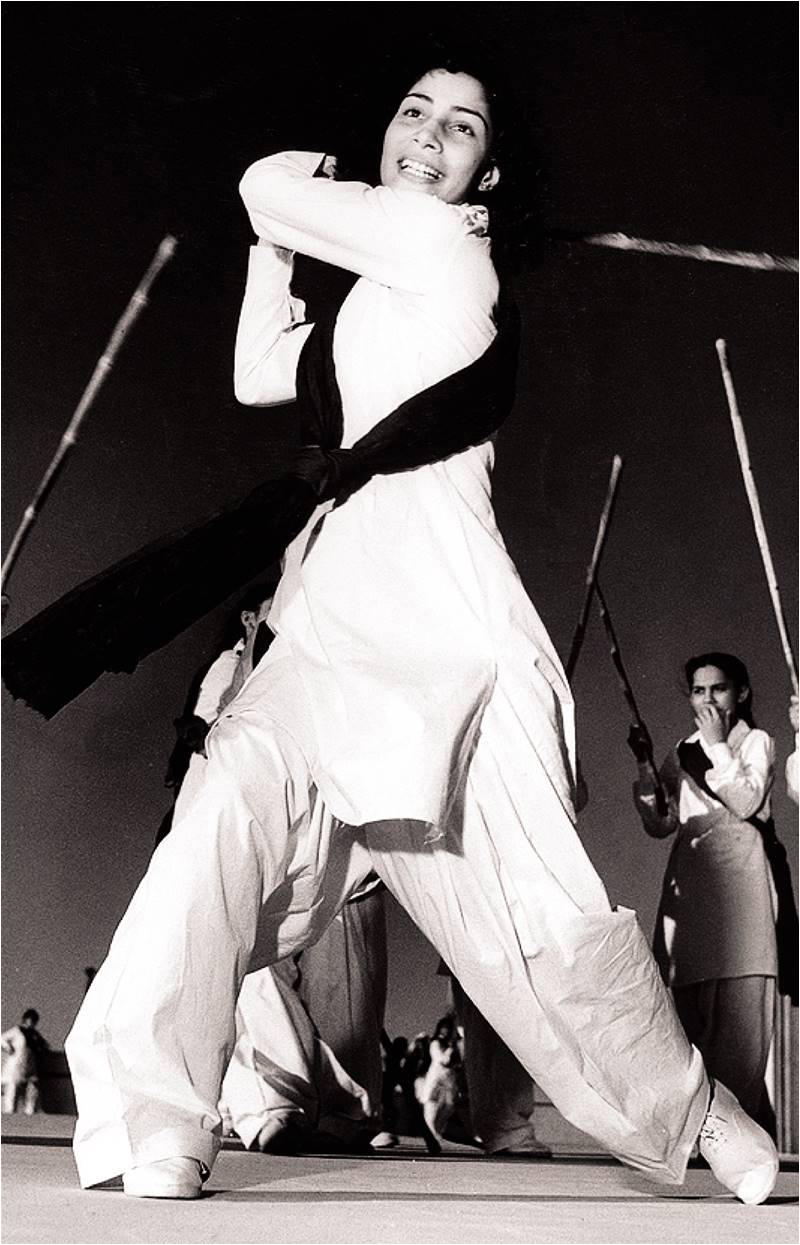

TFT: The contest takes its inspiration from Zeenat Haroon Rashid (21 Jan 1928 - 8 April 2017): a founding member of the Women’s National Guard and your mother. By drawing upon the memory of figures such as your mother, what is it about the legacy of the Muslim women who took a leading role in the Pakistan movement that you wish to highlight?

Syra Vahidi: One thing that I always heard my mother say was that the Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was Pakistan’s first feminist, and that he always believed in women having a prominent role in public life. The women of that era just rallied to the cause, the younger and older ones alike – Begum Liaquat, Begum Fatima Jinnah, my own grandmother Lady Haroon and so many more.

And my mother’s generation were much younger at the time of Partition. They were part of the Muslim League and campaigned for it. The Sindh National Guard was formed to encourage these women from slightly well-known families to act as role-models, so that they could inspire other Muslim women from that period to come forward and play a role in public life and help build Pakistan. And I think that is not something that is so well remembered today, but it is important to point out.

TFT: Your mother Zeenat Haroon Rashid is quoted to have said “Jinnah wanted to show people that in Pakistan, women would do things. We didn’t cover our heads! What nonsense. We were a symbol of progress.” Where and how did this particular idea of progress get lost along the course of our post-Independence history, to the point where expressing such sentiments today places a person firmly outside the Pakistani “mainstream” and in the ranks of people who wish to “impose Western values” on our “Islamic country”?

Syra Vahidi: There has been a misinterpretation of religious values, obviously, but I don’t want to go too far into that, i.e. what is Islam and what is not. In any case, there are certain interpretations in which women are not encouraged to play a prominent role.

My mother, however, always quoted the fact that Prophet(SAW)’s wife Bibi Khadijah (RA) was herself a businesswoman and other Muslim women also took up a role in the life of the community.

I’m not saying that this is the only correct interpretation, but certainly women of my mother’s generation looked at women from Islamic history – including in India, such as Razia Sultan – and concluded that it wasn’t unheard of for Muslim women to play an important role in public life. So people like my mother were women of a certain background and a certain class, and the idea was that they would be role-models for the broader community.

As for how we got to where we are now, it’s important to remember that in some ways the situation of women today is much, much better than that of women even a generation ago. And I’ll elaborate on this. If we talk about women at work, in higher education, in Parliament – I mean these are roles which women have stepped up to take, that were rare even in my own generation. It was not very common for girls to go into higher education even in the 1960s and ‘70s. Girls who had been lucky enough to go to school were often married straight out of school – and I’m talking of middle-class and upper-class women here! So certainly this burgeoning middle-class has rediscovered a role for women in public life, in higher education and at work. We are not just talking about women heading the country, but of women running the State Bank or multinational corporations. There has been a lot of movement and women are taking up roles that were not open to them before.

So yes, perhaps the debate on women’s role is even more polarized today, but maybe we are aware of that much more due to the press, social media and women’s issues being highlighted to a greater extent. On the whole, I think the situation for women is better than it was.

And perhaps it is because they are so prominent in our life today that there is a backlash.

In fact, even if you see the list of where we got all our entries from in our competition, you’ll see that there is a list of about 50 places in Pakistan from where you wouldn’t have dreamed that women would be writing for us. It was a complete revelation to me – every corner of Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab that you think of, as well as Azad Kashmir. And all of them are writing about women’s issues – all of them are concerned about these things. Not all of them are writing very well, but they are engaging with women’s issues. Some of the issues are, in fact, depressingly similar: domestic violence, rape, child sexual abuse, murder and all those dark themes in women’s lives. But there are also lighter moments. One woman writes in a very amusing manner about having to contend with body hair. There are stories about dark complexion and the rishta parade that girls have to go through. Common themes, but some very uplifting stories about hurdles that have been overcome.

I really didn’t expect that there would be so many women willing to talk so bravely about the things that affect their lives.

TFT: What sort of things did the Muslim women in the vanguard of the Pakistan movement – figures such as your mother – read in their time?

Syra Vahidi: I don’t know what many of the other women in the Pakistan Movement read. The famous ones like Begun Shah Nawaz, Begum Liaquat Ali Khan, Mohtarma Fatima Jinnah or my own grandmother – I don’t think they were very highly educated women. I’m not sure that they read very widely.

Certainly my own mother was not educated beyond GCSEs. Higher education for women – unless they were from UP, Aligarh and those regions – was limited.

Perhaps you’re asking the wrong person. You may have to ask someone from that generation. But my mother was very much a part of the Muslim League in Sindh, of which my grandfather Sir Abdullah Haroon was the convener. This was very much a family venture in which they all took part.

My mother was only 18-19 when Pakistan came into being. She was only just out of school. So I really can’t comment on what that generation of Muslim women read. Perhaps a historian like Ayesha Jalal could comment better on this. In fact, there should be some proper work on who the women of that period were and what their reading habits were.

I can only speak about my mother. She went to an English-medium school and read in English. But she read very avidly. Lots of people of her generation, just after Partition, had access to good bookstores – of which there were many in Karachi. People had good libraries at home on all sorts of subjects, be it fiction or non-fiction.

My parents belonged to a Book of the Month Club. It was sort of like the Netflix of their generation. You paid a subscription and received books every month from abroad. So their reading in the 1950s and ‘60s was around the writers of their generation, in English. I know that my mother had a working knowledge of Urdu but she certainly did not read literature in Urdu.

TFT: The format seems fairly open-ended, as long as it is prose and pertains to a Pakistani experience. Are you concerned that the judges might have difficulty in deciding the best writing among entries of such diverse format and subject matter?

Syra Vahidi: This being the first year of the prize, I didn’t know whether we would get 50 entries, or 100 – or even entries of any quality. We weren’t even sure if the quality of writing would be worth giving 100,000 rupees to. So we kept it as wide as possible.

Even going forward, the theme will always be “Women and Pakistan”, meaning that there should be women at the centre of the writing and there should be a sense of place, i.e. Pakistan. If it’s not set in Pakistan, the country must still feature in some prominent way.

If you look at the FAQs on our website, we’ve made it very obvious as to what sort of thing we were looking for, as far as the theme is concerned. Within that, they could write fiction, non-fiction, memoirs, essays, etc. And it was really difficult for our judges to compare, say, an excellent memoir with very good short stories.

So we’ve decided that, going forward, we’ll have a distinction between fiction and non-fiction. The theme will always be “Women and Pakistan”. Maybe next year we’ll focus on memoir, biography, narrative essay and so on. And then the year after that we might go back to short stories.

Next year the format will not be so diverse. It will be non-fiction.

TFT: What about the writing entries in the competition has struck you the most, so far?

Syra Vahidi: This first year, as I mentioned earlier, was very much an experiment, and we’ll be refining things as we go along.

The writing has been so phenomenally good that our judges – many of whom have served on international writing juries – were completely knocked out by its high quality.

I was quite surprised by the honesty and bravery with which some of these women told their stories.

Also, I was struck by how good the best of the entries were. These were very sophisticated and eloquent pieces indeed. I think some of the contestants are professional writers, of course – not necessarily even based in Pakistan. But I did not expect to see such fine samples of writing in the first edition of this competition.

Syra Vahidi: One thing that I always heard my mother say was that the Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was Pakistan’s first feminist, and that he always believed in women having a prominent role in public life. The women of that era just rallied to the cause, the younger and older ones alike – Begum Liaquat, Begum Fatima Jinnah, my own grandmother Lady Haroon and so many more.

And my mother’s generation were much younger at the time of Partition. They were part of the Muslim League and campaigned for it. The Sindh National Guard was formed to encourage these women from slightly well-known families to act as role-models, so that they could inspire other Muslim women from that period to come forward and play a role in public life and help build Pakistan. And I think that is not something that is so well remembered today, but it is important to point out.

TFT: Your mother Zeenat Haroon Rashid is quoted to have said “Jinnah wanted to show people that in Pakistan, women would do things. We didn’t cover our heads! What nonsense. We were a symbol of progress.” Where and how did this particular idea of progress get lost along the course of our post-Independence history, to the point where expressing such sentiments today places a person firmly outside the Pakistani “mainstream” and in the ranks of people who wish to “impose Western values” on our “Islamic country”?

Syra Vahidi: There has been a misinterpretation of religious values, obviously, but I don’t want to go too far into that, i.e. what is Islam and what is not. In any case, there are certain interpretations in which women are not encouraged to play a prominent role.

My mother, however, always quoted the fact that Prophet(SAW)’s wife Bibi Khadijah (RA) was herself a businesswoman and other Muslim women also took up a role in the life of the community.

I’m not saying that this is the only correct interpretation, but certainly women of my mother’s generation looked at women from Islamic history – including in India, such as Razia Sultan – and concluded that it wasn’t unheard of for Muslim women to play an important role in public life. So people like my mother were women of a certain background and a certain class, and the idea was that they would be role-models for the broader community.

As for how we got to where we are now, it’s important to remember that in some ways the situation of women today is much, much better than that of women even a generation ago. And I’ll elaborate on this. If we talk about women at work, in higher education, in Parliament – I mean these are roles which women have stepped up to take, that were rare even in my own generation. It was not very common for girls to go into higher education even in the 1960s and ‘70s. Girls who had been lucky enough to go to school were often married straight out of school – and I’m talking of middle-class and upper-class women here! So certainly this burgeoning middle-class has rediscovered a role for women in public life, in higher education and at work. We are not just talking about women heading the country, but of women running the State Bank or multinational corporations. There has been a lot of movement and women are taking up roles that were not open to them before.

So yes, perhaps the debate on women’s role is even more polarized today, but maybe we are aware of that much more due to the press, social media and women’s issues being highlighted to a greater extent. On the whole, I think the situation for women is better than it was.

And perhaps it is because they are so prominent in our life today that there is a backlash.

In fact, even if you see the list of where we got all our entries from in our competition, you’ll see that there is a list of about 50 places in Pakistan from where you wouldn’t have dreamed that women would be writing for us. It was a complete revelation to me – every corner of Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab that you think of, as well as Azad Kashmir. And all of them are writing about women’s issues – all of them are concerned about these things. Not all of them are writing very well, but they are engaging with women’s issues. Some of the issues are, in fact, depressingly similar: domestic violence, rape, child sexual abuse, murder and all those dark themes in women’s lives. But there are also lighter moments. One woman writes in a very amusing manner about having to contend with body hair. There are stories about dark complexion and the rishta parade that girls have to go through. Common themes, but some very uplifting stories about hurdles that have been overcome.

I really didn’t expect that there would be so many women willing to talk so bravely about the things that affect their lives.

TFT: What sort of things did the Muslim women in the vanguard of the Pakistan movement – figures such as your mother – read in their time?

Syra Vahidi: I don’t know what many of the other women in the Pakistan Movement read. The famous ones like Begun Shah Nawaz, Begum Liaquat Ali Khan, Mohtarma Fatima Jinnah or my own grandmother – I don’t think they were very highly educated women. I’m not sure that they read very widely.

Certainly my own mother was not educated beyond GCSEs. Higher education for women – unless they were from UP, Aligarh and those regions – was limited.

Perhaps you’re asking the wrong person. You may have to ask someone from that generation. But my mother was very much a part of the Muslim League in Sindh, of which my grandfather Sir Abdullah Haroon was the convener. This was very much a family venture in which they all took part.

My mother was only 18-19 when Pakistan came into being. She was only just out of school. So I really can’t comment on what that generation of Muslim women read. Perhaps a historian like Ayesha Jalal could comment better on this. In fact, there should be some proper work on who the women of that period were and what their reading habits were.

I can only speak about my mother. She went to an English-medium school and read in English. But she read very avidly. Lots of people of her generation, just after Partition, had access to good bookstores – of which there were many in Karachi. People had good libraries at home on all sorts of subjects, be it fiction or non-fiction.

My parents belonged to a Book of the Month Club. It was sort of like the Netflix of their generation. You paid a subscription and received books every month from abroad. So their reading in the 1950s and ‘60s was around the writers of their generation, in English. I know that my mother had a working knowledge of Urdu but she certainly did not read literature in Urdu.

TFT: The format seems fairly open-ended, as long as it is prose and pertains to a Pakistani experience. Are you concerned that the judges might have difficulty in deciding the best writing among entries of such diverse format and subject matter?

Syra Vahidi: This being the first year of the prize, I didn’t know whether we would get 50 entries, or 100 – or even entries of any quality. We weren’t even sure if the quality of writing would be worth giving 100,000 rupees to. So we kept it as wide as possible.

Even going forward, the theme will always be “Women and Pakistan”, meaning that there should be women at the centre of the writing and there should be a sense of place, i.e. Pakistan. If it’s not set in Pakistan, the country must still feature in some prominent way.

If you look at the FAQs on our website, we’ve made it very obvious as to what sort of thing we were looking for, as far as the theme is concerned. Within that, they could write fiction, non-fiction, memoirs, essays, etc. And it was really difficult for our judges to compare, say, an excellent memoir with very good short stories.

So we’ve decided that, going forward, we’ll have a distinction between fiction and non-fiction. The theme will always be “Women and Pakistan”. Maybe next year we’ll focus on memoir, biography, narrative essay and so on. And then the year after that we might go back to short stories.

Next year the format will not be so diverse. It will be non-fiction.

TFT: What about the writing entries in the competition has struck you the most, so far?

Syra Vahidi: This first year, as I mentioned earlier, was very much an experiment, and we’ll be refining things as we go along.

The writing has been so phenomenally good that our judges – many of whom have served on international writing juries – were completely knocked out by its high quality.

I was quite surprised by the honesty and bravery with which some of these women told their stories.

Also, I was struck by how good the best of the entries were. These were very sophisticated and eloquent pieces indeed. I think some of the contestants are professional writers, of course – not necessarily even based in Pakistan. But I did not expect to see such fine samples of writing in the first edition of this competition.