Among the trio of creators of an enchanting eastern melody, while the singer gets the most acclaim and the composer an honourable mention, the lyricist often goes unnoticed. That is a tragedy because a memorable song cannot emerge unless it evolves from good words. A great song consists of fascinating lyrics and a hypnotizing voice knit around mesmerizing tune. The presence of all these three essential components creates harmony; one or two would just writhe around agonizingly without finding any bliss without the third.

This article is about Tanvir Naqvi, one of the greatest Geet (song) writers of the Indo-Pak film industry, and two of his Geets; a film song and a national song.

The Geet is one of the numerous forms of Urdu/Hindi poetry. As opposed to the more sacred Ghazal, where one verse is unrelated in meaning to others, a Geet has a central theme. The two genres also differ in rhyme (Radif and Kafia) though they are similar in that their verses mostly consist of two hemistichs separated by a caesura. While a Ghazal traditionally is melancholy, conveying the bitterness of an unconsummated love, it doesn’t have the capacity for expressing variety of sentiments. The Geet is versatile: capable of expressing any kind of mood and suitable for film songs.

Tanvir was a Geet writer par excellence and amongst the greatest film-song writers in the Indian Subcontinent. In fact, it would not be implausible to state that he was one of the pioneers of film lyrics as we know them to be.

He was born in February 1919 in Lahore and named Syed Khurshid Ali. He lived inside Bhaati Gate on one of the streets off Bazaar-e-Hakiman, which has been the abode of such literary geniuses as the famed Hakeem brothers of Ranjit Singh’s court, Allama Iqbal, Agha Hashar, A.R. Kardar, Sir Abdul Qadir and many others.

Tanvir belonged to a learned family and was at home in Persian as well as in Urdu and Punjabi. Mastery of three languages provided him with a vast vocabulary that he admirably used in crafting his songs of simple wording but profound meanings. With his natural propensity for poetry, he started writing for films at an incredibly early age. According to the book Dil ka Diya Jalaya (Lighting the Lamp of the Heart) by Rahim Sikkedar, Tanvir was called to Bombay by the great film director A.R. Kardar in 1933. If that be the case, then Tanvir was only 14 years of age at the time.

The famed writer Mirza Adeeb says in his essay Qissa aik Kitab ka (The Tale of a Book) included in Sikkedar’s book that on learning that Tanvir was writing Ghazals, he had advised him to write Geets – as in Urdu, there was an abundance of Ghazal writers but a shortage of Geet writers. Whether Tanvir followed this advice or his natural propensity, he went on to write great Geets. He found success at a young age. His first film song is listed for A.R. Kardar’s 1941-released Swami, though he is also mentioned as a lyricist for a song in a 1937-film titled Khudai Khidmatgar, when Tanvir would have been 18 years old. However, his popularity and fame rose at the age of 22 with his immortal lyrics for the 1946 film Anmol Gharri.

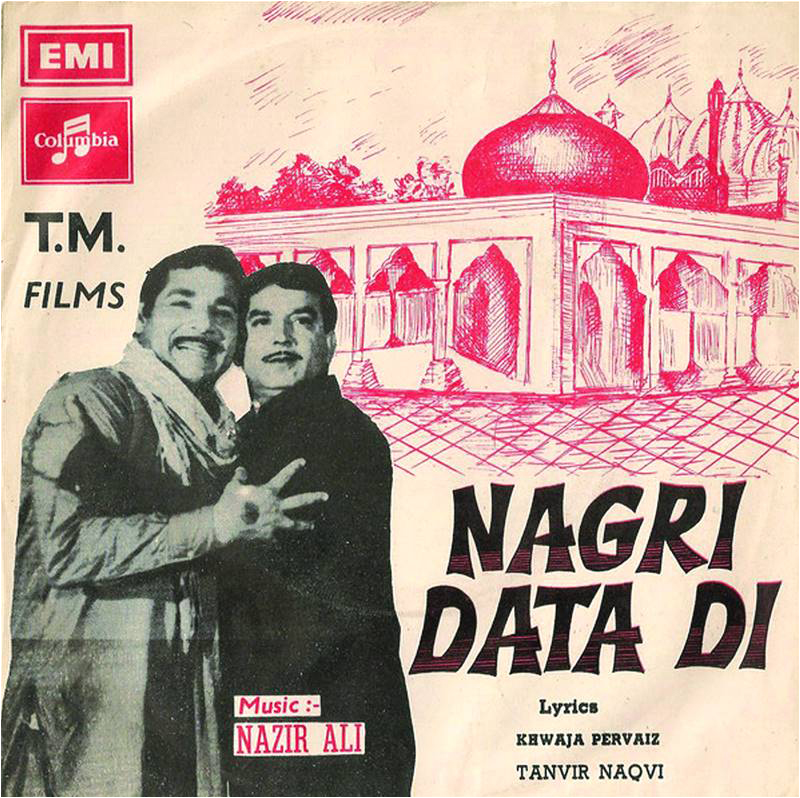

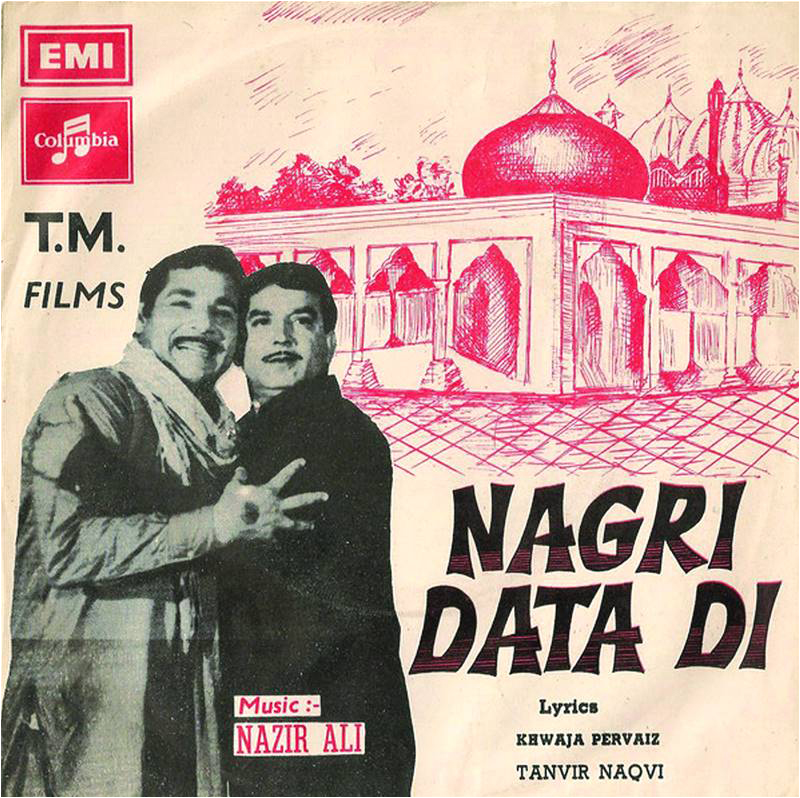

This article, as indicated earlier, is about Tanvir and two of his creations; a song for the 1962 Pakistani film Azra, composed by Master Inayat Hussain in the husky voice of Saleem Raza; and a patriotic anthem rendered touchingly by Noor Jahan in an emotive composition by musician Hassan Latif Lilak.

First the song: “Jaan-e-Baharan-Rashk-e-Chaman” carries one of the most rhythmical verses in Indo-Pak film songs. Its sublime phrasing is woven in light-weight loving words, flowing blissfully through the soulful visions of a serene life full of joy and satiation. The song doesn’t make the listener think, but instead to close eyes and let the words breeze past them.

It is mentioned by Sikkedar, as noted on a Facebook page dedicated to Tanvir Naqvi, that music director Master Inayat Hussain didn’t want a routine Urdu song for his film Azra (1962) as the story was based on Arab background. Tanvir Naqvi came up with this poem that is an exquisite amalgam of Arabic, Persian and Urdu. It is full of two-word phrases that have Arabic texture. ‘Jaan-e-Bahran’, ‘Jaan-e-Mann’, ‘Shamm-e-FarozaN’, ‘Mushk-e-Khutan’, ‘Mauj-e-Saba’, ‘Rashk-e-Chaman’, ‘Ghuncha Dahan’, ‘Seemi badan’, ‘Naz Afreen’, ‘Naz Parwar’, ‘Khanda Jabein’ and ‘Sheerin Sukhan’ are not Arabic words but are Arabic-sounding. They are cleverly crafted to be so lightweight that they effortlessly leave the tongue. They are like a soft morning breeze that wafts through one’s soul. The real genius of the poet lies in conceiving so many of these metaphors, all similarly conveying a vision of ephemeral beauty.

The song, consisting of four tercets, neither makes any demand on the beloved nor expresses any amorous desire. It does not present any grievance or grief either. It only extols her beauty in lyrical phrases.

The verses of the Geet are simple statements of adoration. The opening line ‘Jaane Baharan Rashke Chaman’ is a superb compliment that would have done honour to a Delhi maestro in the twilight years of the Mughal court. The next line ‘Ghuncha Dahan, Seemi Badan’ is hypnotizing. It alleviates mental burdens and makes one look at nothing in particular but far away over the horizon in serene contemplation. In the third line of this tercet, ‘Aey Jaan-e-Mann, Jaan-e-Baharan’, the lover is in total submission to the beloved. This line can be transliterated as ‘Oh my soul; the soul of springs.’

The Geet is very hard to translate. Even the simple word-for-word translation is a challenging affair because the English language lacks commensurate amiable phrases. If some equivalent words are somehow found, the spirit would be lost in translation. The second tercet of the song continues the reverential aura created by the first;

Janat ki hooreiN tujh pe fida

Raftar jeise mauj’ey saba

RangeeN ada.tauba shikan

(“Angels are captivated by you

Your bearing is of soft breeze

Your charms break vows of denial”)

The third tercet reads as follows:

Shamm-e-farozan aankheN teri

har ik nazar meiN jaadugary

zulfeiN teri mushk-e-khutan

(“Your eyes; lighted lamps

Each gaze; magically alluring

Your tresses; bewitching aroma”)

The last tercet is equally charming:

Ae naaz parwar naaz aafreen

laakhon haseen hain tujh sa nahin

khanda jabein sheerin sukhan

(“Oh! the one with charming attitude

Many are elegant but none like you

Engaging looks, eloquent diction”)

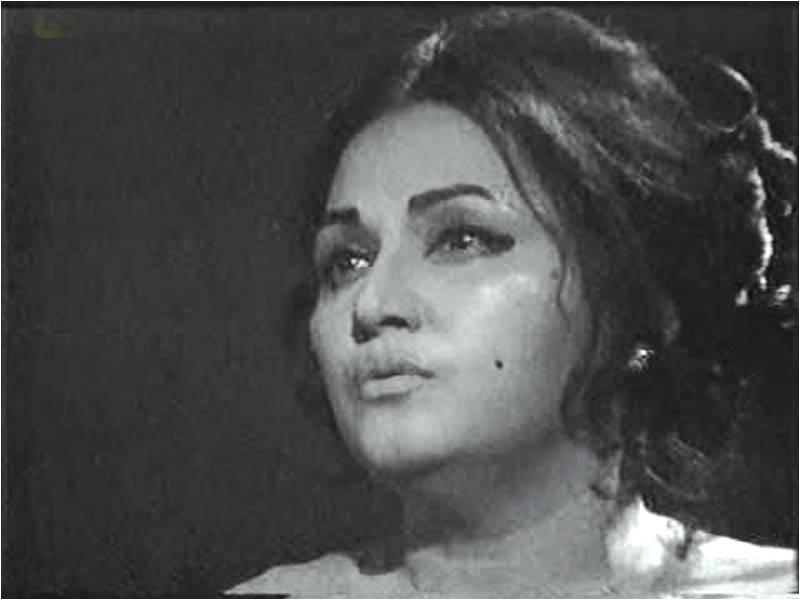

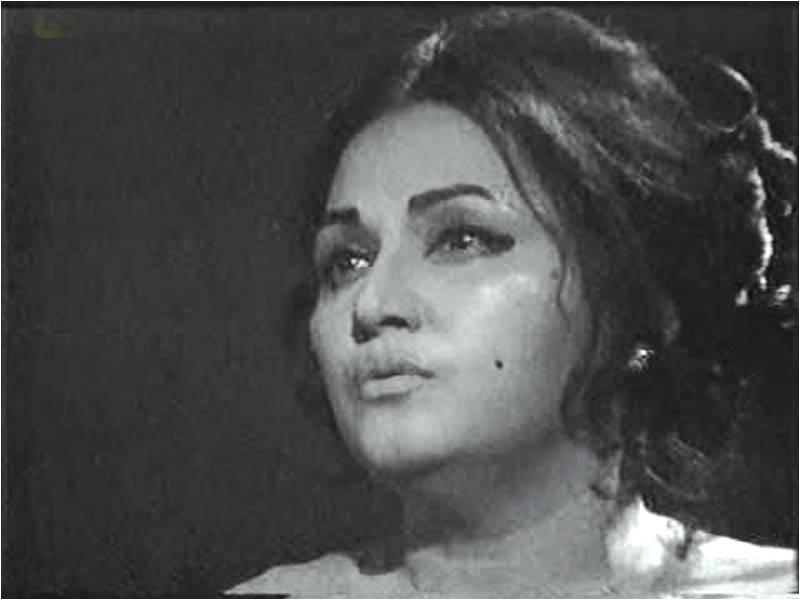

The song has been enacted on film actors Ijaz and Neelo. While the dance by Neelo is appealing, Ijaz appears wooden and stiff, unable to convey the feelings emanating from the words that he is lip-singing. With limited acting abilities, he has not been able to do justice to the beautiful wording.

The second poem that will keep Tanvir immortal is a national song. Few anthems can match the appeal of ‘Rang laega ShaheedoN ka Lahoo’.

This poem, rendered in a soulful style by Noor Jahan in the music of Hassan Latif Lilak, is not about death but about living, not despondency but hope, not a break from future but continuity with past. The reward that the poet offers for ultimate sacrifice is not a place under a shaded tree in a sacred garden along a mythical canal; it promises a vision of a hallowed land in this very world where we all hope to find peace.

There is no better interpretation of martyrdom than found in this national song and stands in vast contrast with some of the currently written national songs that are centred around hyper-religious imagery.

Tanvir’s memory is kept alive by some books and articles, and also by a well maintained Facebook page by one of his fans. However, his greatest legacy is his nearly 600 songs in nearly 200 films, including such films as Anmol Garhi, Jugnu, Shirin Farhad, Anarkali, Moseqaar, Koel, Azra, Att Khuda da Vair etc. whose songs refuse to fade away and continue to be popular even after the lapse of over half a century. He also wrote two unforgettable naats; ‘Shah-e-Madina Yasrab key Wali’ and ‘Jo na hota tera jamal hi, Tou jahan tha khawab-o-khayal hi, Sallu Alaihe Wa Aalehi’.

Tanvir Naqvi will be remembered for a very long time to come, indeed!

Parvez Mahmood retired as a Group Captain from PAF and is now a software engineer. He lives in Islamabad and writes on social and historical issues. He can be reached at parvezmahmood53@gmail.com

This article is about Tanvir Naqvi, one of the greatest Geet (song) writers of the Indo-Pak film industry, and two of his Geets; a film song and a national song.

The Geet is one of the numerous forms of Urdu/Hindi poetry. As opposed to the more sacred Ghazal, where one verse is unrelated in meaning to others, a Geet has a central theme. The two genres also differ in rhyme (Radif and Kafia) though they are similar in that their verses mostly consist of two hemistichs separated by a caesura. While a Ghazal traditionally is melancholy, conveying the bitterness of an unconsummated love, it doesn’t have the capacity for expressing variety of sentiments. The Geet is versatile: capable of expressing any kind of mood and suitable for film songs.

Tanvir was a Geet writer par excellence and amongst the greatest film-song writers in the Indian Subcontinent. In fact, it would not be implausible to state that he was one of the pioneers of film lyrics as we know them to be.

He was born in February 1919 in Lahore and named Syed Khurshid Ali. He lived inside Bhaati Gate on one of the streets off Bazaar-e-Hakiman, which has been the abode of such literary geniuses as the famed Hakeem brothers of Ranjit Singh’s court, Allama Iqbal, Agha Hashar, A.R. Kardar, Sir Abdul Qadir and many others.

Tanvir belonged to a learned family and was at home in Persian as well as in Urdu and Punjabi. Mastery of three languages provided him with a vast vocabulary that he admirably used in crafting his songs of simple wording but profound meanings. With his natural propensity for poetry, he started writing for films at an incredibly early age. According to the book Dil ka Diya Jalaya (Lighting the Lamp of the Heart) by Rahim Sikkedar, Tanvir was called to Bombay by the great film director A.R. Kardar in 1933. If that be the case, then Tanvir was only 14 years of age at the time.

According to the book Dil ka Diya Jalaya (Lighting the Lamp of the Heart) by Rahim Sikkedar, Tanvir was called to Bombay by the great film director A.R. Kardar in 1933. If that be the case, then Tanvir was only 14 years of age at the time

The famed writer Mirza Adeeb says in his essay Qissa aik Kitab ka (The Tale of a Book) included in Sikkedar’s book that on learning that Tanvir was writing Ghazals, he had advised him to write Geets – as in Urdu, there was an abundance of Ghazal writers but a shortage of Geet writers. Whether Tanvir followed this advice or his natural propensity, he went on to write great Geets. He found success at a young age. His first film song is listed for A.R. Kardar’s 1941-released Swami, though he is also mentioned as a lyricist for a song in a 1937-film titled Khudai Khidmatgar, when Tanvir would have been 18 years old. However, his popularity and fame rose at the age of 22 with his immortal lyrics for the 1946 film Anmol Gharri.

This article, as indicated earlier, is about Tanvir and two of his creations; a song for the 1962 Pakistani film Azra, composed by Master Inayat Hussain in the husky voice of Saleem Raza; and a patriotic anthem rendered touchingly by Noor Jahan in an emotive composition by musician Hassan Latif Lilak.

First the song: “Jaan-e-Baharan-Rashk-e-Chaman” carries one of the most rhythmical verses in Indo-Pak film songs. Its sublime phrasing is woven in light-weight loving words, flowing blissfully through the soulful visions of a serene life full of joy and satiation. The song doesn’t make the listener think, but instead to close eyes and let the words breeze past them.

It is mentioned by Sikkedar, as noted on a Facebook page dedicated to Tanvir Naqvi, that music director Master Inayat Hussain didn’t want a routine Urdu song for his film Azra (1962) as the story was based on Arab background. Tanvir Naqvi came up with this poem that is an exquisite amalgam of Arabic, Persian and Urdu. It is full of two-word phrases that have Arabic texture. ‘Jaan-e-Bahran’, ‘Jaan-e-Mann’, ‘Shamm-e-FarozaN’, ‘Mushk-e-Khutan’, ‘Mauj-e-Saba’, ‘Rashk-e-Chaman’, ‘Ghuncha Dahan’, ‘Seemi badan’, ‘Naz Afreen’, ‘Naz Parwar’, ‘Khanda Jabein’ and ‘Sheerin Sukhan’ are not Arabic words but are Arabic-sounding. They are cleverly crafted to be so lightweight that they effortlessly leave the tongue. They are like a soft morning breeze that wafts through one’s soul. The real genius of the poet lies in conceiving so many of these metaphors, all similarly conveying a vision of ephemeral beauty.

The second poem that will keep Tanvir immortal is a national song. Few anthems can match the appeal of ‘Rang laega ShaheedoN ka Lahoo’

The song, consisting of four tercets, neither makes any demand on the beloved nor expresses any amorous desire. It does not present any grievance or grief either. It only extols her beauty in lyrical phrases.

The verses of the Geet are simple statements of adoration. The opening line ‘Jaane Baharan Rashke Chaman’ is a superb compliment that would have done honour to a Delhi maestro in the twilight years of the Mughal court. The next line ‘Ghuncha Dahan, Seemi Badan’ is hypnotizing. It alleviates mental burdens and makes one look at nothing in particular but far away over the horizon in serene contemplation. In the third line of this tercet, ‘Aey Jaan-e-Mann, Jaan-e-Baharan’, the lover is in total submission to the beloved. This line can be transliterated as ‘Oh my soul; the soul of springs.’

The Geet is very hard to translate. Even the simple word-for-word translation is a challenging affair because the English language lacks commensurate amiable phrases. If some equivalent words are somehow found, the spirit would be lost in translation. The second tercet of the song continues the reverential aura created by the first;

Janat ki hooreiN tujh pe fida

Raftar jeise mauj’ey saba

RangeeN ada.tauba shikan

(“Angels are captivated by you

Your bearing is of soft breeze

Your charms break vows of denial”)

The third tercet reads as follows:

Shamm-e-farozan aankheN teri

har ik nazar meiN jaadugary

zulfeiN teri mushk-e-khutan

(“Your eyes; lighted lamps

Each gaze; magically alluring

Your tresses; bewitching aroma”)

The last tercet is equally charming:

Ae naaz parwar naaz aafreen

laakhon haseen hain tujh sa nahin

khanda jabein sheerin sukhan

(“Oh! the one with charming attitude

Many are elegant but none like you

Engaging looks, eloquent diction”)

The song has been enacted on film actors Ijaz and Neelo. While the dance by Neelo is appealing, Ijaz appears wooden and stiff, unable to convey the feelings emanating from the words that he is lip-singing. With limited acting abilities, he has not been able to do justice to the beautiful wording.

The second poem that will keep Tanvir immortal is a national song. Few anthems can match the appeal of ‘Rang laega ShaheedoN ka Lahoo’.

This poem, rendered in a soulful style by Noor Jahan in the music of Hassan Latif Lilak, is not about death but about living, not despondency but hope, not a break from future but continuity with past. The reward that the poet offers for ultimate sacrifice is not a place under a shaded tree in a sacred garden along a mythical canal; it promises a vision of a hallowed land in this very world where we all hope to find peace.

There is no better interpretation of martyrdom than found in this national song and stands in vast contrast with some of the currently written national songs that are centred around hyper-religious imagery.

Tanvir’s memory is kept alive by some books and articles, and also by a well maintained Facebook page by one of his fans. However, his greatest legacy is his nearly 600 songs in nearly 200 films, including such films as Anmol Garhi, Jugnu, Shirin Farhad, Anarkali, Moseqaar, Koel, Azra, Att Khuda da Vair etc. whose songs refuse to fade away and continue to be popular even after the lapse of over half a century. He also wrote two unforgettable naats; ‘Shah-e-Madina Yasrab key Wali’ and ‘Jo na hota tera jamal hi, Tou jahan tha khawab-o-khayal hi, Sallu Alaihe Wa Aalehi’.

Tanvir Naqvi will be remembered for a very long time to come, indeed!

Parvez Mahmood retired as a Group Captain from PAF and is now a software engineer. He lives in Islamabad and writes on social and historical issues. He can be reached at parvezmahmood53@gmail.com