The book under review is an ambitious attempt to write about the geographical area now known as Pakistan from the ancient civilizations of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro till the present day. Such histories of the Longue Durée are difficult to write, since there is much to be compressed and the problem of the historian is more about what to leave out than what to include.

In this instance, the author has done well to start with a past which the conventional historians of Pakistan leave out since it is not Muslim. Tahir Kamran has, therefore, offered a necessary corrective to this kind of ideological construction of history.

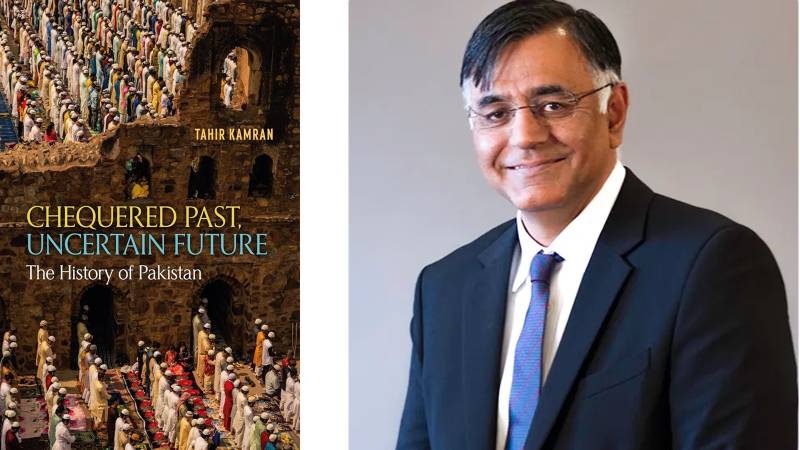

Title: Chequered Past, Uncertain Future: the History of Pakistan

Author: Tahir Kamran

Publishers: Ilqa Publications, an Imprint of Readings, Pp 565

Year: 2024

After this, there are chapters on Muslim rule—the Sultanates and the Mughal empire and its fragments—over much of India. Here Tahir Kamran contends first that this rule is not Muslim because Hindus and people of other religions also served in the apparatus of power; and, secondly, that the Muslims were not foreigners. This is partly true in that the rulers were more concerned with their power rather than with religion as such, and also that they intermarried and settled down in India and, thus, became as Indian as anybody else. However, the British also were not concerned with anything but their power, they too employed Indians in the bureaucracy and the army. It is true, however, that the Muslim sovereign did not send money from India to wherever they may have come from, whereas, at least in the beginning, the British did. Also, the British never settled down, nor did they become Indians. However, essentially both were forms of empire building and the dominant power was different in essential ways from the dominated masses. But, to distinguish between my argument and that of the upholders of Hindutva in India and in agreement with Tahir Kamran, I must add that the caste Hindus, if their claim of being Aryans is correct (genetics tells us that no claim about racial purity is correct), were outsiders and they too, like Muslims, settled down in India.

Despite my criticism that the author is biased in favour of Imran Khan and against Nawaz Sharif and Asif Zardari, I think the book is a product of enormous intellectual labour. It creditably covers a very long period in the history of human beings in South Asia

The account of the rise of Muslim separatism and the partition of India is concise, but the essential facts are given. The exchange of population and the massacres in 1947 have been touched upon and the reference to Faiz’s poem on them is much to be appreciated. Anyway, the main problem I have is that neither Jinnah, nor Nehru, Gandhi or the British actually imagined the exchange of population and the carnage which would follow. This point has not been treated as it deserved.

While Tahir Kamran does not criticize Jinnah’s decision to become the first governor general of Pakistan, he does write that Jinnah did, however, want a “super-GG” in Delhi for matters of arbitration (p 111). However, the fact that Jinnah did not become a constitutional figurehead as Governor-General, did need questioning by the historian. This questioning comes later when, unlike conventional Pakistani historians, Tahir Kamran makes it clear that Mr Jinnah’s own way of ruling the state with bureaucrats and leaving the office-holding politicians out in the cold, was not conducive to democratic tradition. The question of the accession of states has been given the importance it deserves. However, the fact that the idea of leaving the decision about accession to the rulers, like Hari Singh of Jammu and Kashmir, was that of Jinnah and the British and Nehru was against it. Tahir Kamran agrees that Pakistan used the Pashtun tribesmen in this war. Since many Pakistani historians deny it, it is to be appreciated.

The chapters on the derailing of democracy up to 1958 when Ayub Khan imposed took charge of the country under the military are clear and succinct. Ayub did make the country economically stronger but he did not ensure that wealth trickled down to the masses and, above all, he alienated East Pakistan by developing West Pakistan and especially investing in the armed forces. The result of this was the 1971 war when, under General Yahya, there was a war and Bangladesh was created. The author adequately covers the political events leading to the war, the use of the violence by the state was “in defence of a unitary state and viceregal tradition,” he does not give as much space to Bengali suffering as many recent histories do now (p. 208). Moreover, most states do take such actions and the viceregal state we know about most (British India) actually held round-table conferences and took no such action.

The chapter on Bhutto is rightly entitled the “era of populism.” Mujib and Bhutto were both populist leaders who achieved cult status which is always harmful for societies. The author is right that Bhutto can be credited with many achievements, including his new foreign policy orientation, but he had personality defects which led to his downfall. Zia-ul-Haq, who followed Bhutto, changed the orientation of Pakistani society, which curtailed women’s and minorities’ rights. He also joined the first war of the USA in Afghanistan (against the USSR) the consequences of which we face even now. The author’s final verdict on Zia’s rule is that it “promoted harsh reprisals, impunity and wilfulness.” Intolerance increased and remains entrenched even now.

Up to now Tahir Kamran writes without rancour and describes historical events in a dispassionate and objective manner. However, when he first mentions the name of Asif Zardari in the chapter on Zia, he describes him as being “with no scruples worth mentioning,” and then says that “for him, as for the Sharifs, everything had a price, with values, ethics, honesty and integrity reduced to mere cliches.” (p. 270). This sets the tone for Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif’s rule in the next two chapters. The democracy they established is called “establishmentarian democracy,” which is true since the military had power over the PMs, but it is also true of all governments including the PTI one. Political personalities are reviled without the kind of evidence which can stand in a court of law. While writing about both Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif’s revolving turns at the helm of affairs, the author’s main focus is on the political events which are, of course, shady. Such things as positive policies—such as infrastructural developments—are underplayed or ignored.

While it is true that the military pulled the strings of both government, it is also true that they had at least tried through pacts not to strengthen the military in politics as it was not in the interest of civilian authority (p 359). Of course, this lesson came late as by then General Musharraf had ruled Pakistan keeping both leaders away for a long time, but it is a significant development. The author has rightly mentioned how Musharraf’s government entered the ‘War on Terror’ and how it brought terror in the shape of mass bombings in Pakistan. Here the author has brought in his knowledge of literature, mostly literature in English, to give a deeper analysis of the Pakistani mind regarding the love-hate relationship with the USA and the militancy which stalked the land (p 371-374). However, the fact that both Musharraf and then the governments which followed him including that of PTI, agreed with the military’s narrative that the Taliban were Pakistan’s strategic assets and should be strengthened even while handing some of them over to the USA, has not been given the importance it deserved nor criticized.

The era following Musharraf is called “The Decade of Uncertainty 2008-18,” which it certainly was. But it was so uncertain because there was so much terrorism not because of the, admittedly many, faults and foibles of politicians like Zardari or Sharif. The policies had been wrong and were still wrong and this point needs the kind of emphasis which it has not received. One thing, however, even these leaders did achieve: they made political transitions possible. This promised political stability which turned into stability from 2013 onwards. One could even argue that it was this strengthening of civilian authority which alarmed the establishment which now wanted a challenger in the form of Imran Khan. However, as proof of this is not available, this point need not be laboured.

While other things do not detract from the books worth, the author’s emotional involvement with Imran Khan does. It first becomes apparent in the language he uses for the PPP and the PML-N figures, and the fact that he spends more space and time on their shady deals and weaknesses than their achievements. With this in mind, the author’s laudatory description of Imran Khan as the “icon” who needs no introduction comes as no surprise. There is no doubt that he was an icon, but the brand of politics he inspired is populist. However, the author does not use the word populist for him as he does for Bhutto. Nor does he point out that the PTI, following him, uses divisive and strong language (populists do that throughout history), which has made Pakistan more intolerant than before. Nor, indeed, does the author cite the role of the military in building up cricketing hero image into a political leader one. There is evidence that some help was given by the establishment to the PTI in winning the election of 2018 and for a long time the COAS, General Bajwa, was said to be “on the same page” as the government, as if civilian supremacy does not exist even as a theoretical concept. However, help does not mean that the election was rigged or that Imran Khan had not won it. All it implies is that the establishment, which has made and unmade governments, was active and this has been ignored by the author. In this case the various measures the PTI government took in the interest of the people have been given full coverage which, I think, is how it should be but in the case of all governments.

One of the strengths of Tahir Kamran’s book is that he looks at the way the civil-military relations have impacted Pakistan’s democracy in ways which make it a praetorian state. This analysis is suspended only during the PTI’s rule but it is revived, as it should be, when he is removed from power in the same way as other PMs are—apparently through legal processes (vote of no confidence) and actually through the stick and the carrot method to which the parliamentarians are subjected. His epilogue contains advice—democracy, rule of law, free press—which remain true. This is good advice but the real problem is how to implement it in a country so divided in its opinions and so intolerant that political discussion is impossible. Also, though there is no doubt that Imran Khan is very popular at the moment, the phenomenon of being a cult figure needs deeper analysis. History tells us that, barring Nelson Mandela, cult figures touch the deepest chords of negative emotions of the people. Is this problematic? This deserves an answer from historians as well as political scientists and even psychologists.

Despite my major criticism that the author is biased in favour of Imran Khan and against Nawaz Sharif and Asif Zardari, I think the book is a product of enormous intellectual labour. It creditably covers a very long period in the history of human beings in South Asia. Hence, I commend the book especially because of its departure from conventional historiography in Pakistan. I think it is a useful book, especially for students who want to grasp the essence of the historical panorama of Pakistan and discover how history is intertwined with politics.