Much of the vast literature on Vietnam focuses on the conduct of the war and what happened after it ended. General McMaster, who also holds a doctorate in history, focuses on the “formative years” of the war, from 1962-65.

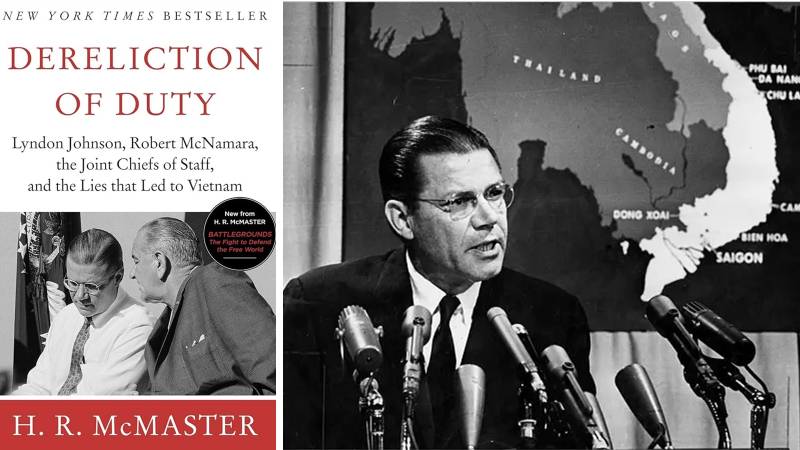

The spotlight is on two individuals, President LB Johnson, and Robert McNamara, who was appointed Secretary of Defence by President Kennedy. A graduate of the Harvard Business School, McNamara headed the Ford Motor Company when he was called to duty by Kennedy.

He was trained in Systems Analysis but had no training in the art of warfare. Yet, as early as in 1962, he made the sweeping statement that the US was winning the war in Vietnam.

He endeared himself to Johnson, to the point that the President would often pay no attention to the Service Chiefs or to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Indeed, McNamara garnered so much respect from Johnson that at a meeting of the service chiefs with selected members of Johnson’s cabinet, the president, pointing to McNamara, said that he was indebted to him because he “gave up a great deal of his hobbies and his pleasures and hundreds of thousands of dollars a year […] to come here and serve the country.”

President Johnson hid the US’s deepening involvement – not just from the press but also from Congress. Troop requisitions were made without Congressional approval

McNamara emerges as a vainglorious man who thought he knew more about war-fighting than the generals. McMaster makes it clear that the US had no clear objective in Vietnam other than to prevent communism from spreading in Southeast Asia, the so-called Domino Theory that came from President Harry Truman’s administration. Once it got involved in Vietnam, the US discovered to its regret that internecine fighting among the South Vietnamese leaders was rampant. The US ambassador told the Vietnamese generals that the Americans were tired of their coups. Adding insult to injury, he snapped: “Do you understand English?”

In the countryside, the Viet Cong had stepped up their guerilla attacks, with the assistance of the North Vietnamese state. The latter was headed by Ho Chi Minh, who had returned from France to Hanoi in 1943 after the French departed from Vietnam.

As the US struggled to unite the South Vietnamese while fighting the Viet Cong and to take on the communists in the North, it began to realise the war was unwinnable. Johnson’s attention was focused elsewhere, notably on his “Great Society” initiative, and on getting re-elected in 1964.

Slowly and steadily, the US found itself pulled into a deepening quagmire, expanding its military presence simply to “preserve its reputation.” Strangely enough, Johnson and McNamara convinced themselves that withdrawing sooner would be worse for their reputation than getting out later. The interests of the American people did not weigh on their mind.

Johnson hid the US’s deepening involvement – not just from the press but also from Congress. Troop requisitions were made without Congressional approval. McNamara “helped Johnson maintain a façade of consultation with Congress even as the president obscured the changing role of the United States in the war.” Before they knew it, the Americans had been sucked into “a quicksand of lies.”

A dubious attack by North Vietnamese patrol boats on US destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964 provided gave the Americans an excuse to begin bombing the North. Attacks by the Viet Cong on US bases in the South were used to justify deploying US ground forces in the South.

McNamara and Johnson insisted that another Korean War was not in the offing, yet an outright lie. The US deployment was criticised by Professor John Kenneth Galbraith, a former US ambassador to India.

As early as the spring of 1965, General Westmoreland had concluded that defeat was imminent. As the war escalated, domestic opposition began to grow and drew in celebrities such as Jane Fonda, who was particularly vocal. The public backlash forced Johnson to drop out of the presidential race in 1968. Richard Nixon won the elections partly on a promise to end the war.

He began peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese and agreed to withdraw all US forces by March 1973. In 1975, the North Vietnamese entered the southern capital of Saigon and as they prepared to storm the American embassy, US Marine helicopters flew off the roof of the American embassy for the last time. The image made it to the front page of newspapers throughout the globe.

While it is not mentioned in the book, the televised disgrace of withdrawal would be repeated in Kabul in September 2021. The US effort to impose a Western-style democracy in Iraq after deposing Saddam Hussein in April 2005 had been yet another failure.

Even though one president after another continues to say that the ghost of Vietnam has been buried, it continues to haunt the United States.

That is what happens when wars are fought with unclear or unattainable objectives that are not grounded in reality. McMaster’s book is based on a review of declassified documents and on several interviews with people who were involved in planning and fighting the war. He finds that even though there were serious disagreements among the service chiefs on how to fight the war, McNamara kept on reassuring Johnson that the US would win the war. In the end, the effort to preserve America’s reputation ended up ruining it and ending Johnson’s political career.

In 1995, McNamara stated, “Eager to get moving, we never stopped to explore fully whether there were other routes to our destination.” He had been warned that “once on the tiger’s back, we cannot be sure of picking the place to dismount.” And yet, “no one was willing to discuss getting out.”

He never accepted blame for his role in perpetuating one of the worst wars in history, which killed 58,000 Americans and upwards of 2 million Vietnamese. In 1968, in the irony of ironies, he was appointed President of the World Bank, a position that he held until 1981.