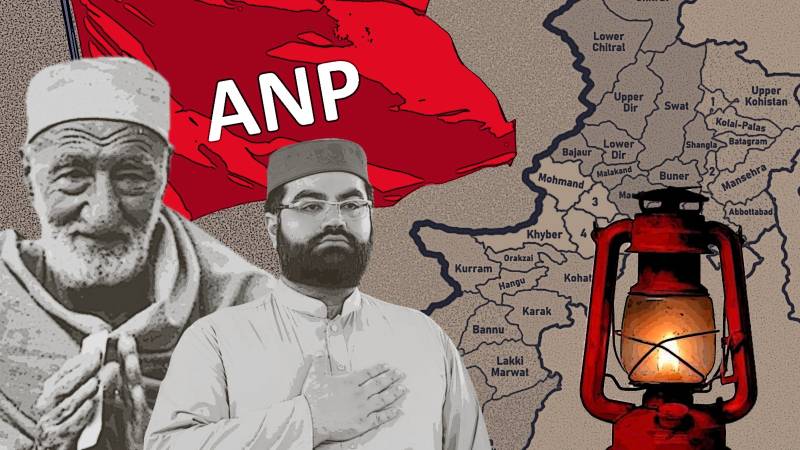

At this point, it is safe to say that the recently concluded general elections were perhaps the most unpopular and unfair elections ever held in Pakistan. Among the political casualties the 2024 general elections threw up was the centre-left nationalist party, Awami National Party (ANP). It managed to win just one seat in its stronghold of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and two seats in the Balochistan assembly. It has been rendered irrelevant in Pakistan's national politics.

While many people did not expect the ANP to reprise its success from 2008 and win a lot of seats in the province, what no one anticipated was the kind of blow the ANP would suffer during the elections.

Last year, people were far more optimistic about ANP's chances in the general elections. They openly expressed that the ANP would win big in the province along with the Maulana Fazal Rahman-led Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI). These commentators had prophesied that the powers that be would divide the province between the JUI-F and the ANP.

But after Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf's (PTI) unexpected performance, where its supported independent candidates won a two-thirds majority in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and became the largest party in the National Assembly, many commentators and political analysts have been proven incorrect.

The astounding ouster of the ANP from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa assembly in these elections has been explained differently by most.

To a layman like me, the factors behind the fall of ANP lie both within and outside the party. These reasons pertain to its leadership, its outdated narratives, and flaws in political maneuvering — in other words — strategies.

The ANP was once led by stalwarts like Wali Khan. When it last won big in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, it was led by the likes of Asfandiyar Wali Khan. Despite its shortcomings, the ANP-led government between 2008-2013 performed relatively well as it fought terrorism and sacrificed many of its workers and leaders in the process. The then-chief minister Amir Haider Hoti is regarded by many as a competent leader whose government not only performed better on the lawmaking front but also delivered to the people in sectors such as education.

The passing of the 18th Amendment in 2010 would not have been possible without support from the ANP. Additionally, the ANP effectively negotiated for the province's rights under the National Finance Commission (NFC) Award.

The ANP could no longer use the Pushtun victim card as a new, more organic grassroots political movement had emerged around it, the PTM

Many ANP sympathisers, however, would like to see the presidency of the ANP move out of its traditional home at Wali Bagh and rest with an ideological successor such as Amir Haider Hoti. But this has not happened. Asfandiyar Wali Khan's son was 'elected' the party's president. This has disappointed many supporters who believe Aimal has been unable to lead the party effectively. Many party supporters consider Aimal to be a non-serious leader. Keeping the party's leadership confined to Wali Bagh has pushed the party deeper into the casket of dynastic parties, where it is joined by the likes of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan People's Party (PPP).

Secondly, the Pushtun-centric narrative no longer works. This narrative was adopted and championed by the youth-led rights movement, the Pushtun Tahaffuz (protection) Movement (PTM). This movement addressed the wounds suffered by victims of the war on terror and missing persons by raising specific issues and fighting for their rights openly. It also challenged Pakistan's powerful establishment, facing persecution from state institutions and the courts in return.

The ANP was very careful in supporting PTM's narrative. It even expelled a few stalwarts like Afrasiab Khattak and Bushra Gohar from its ranks for supporting the Manzoor Pashteen-led PTM. This move was seen by many as an attempt by the ANP to woo the establishment and secure another term in the province.

The ANP could no longer use the Pushtun victim card as a new, more organic grassroots political movement had emerged around it. The ANP, too, could no longer project itself as anti-establishment as it used to be because its leadership fell silent on issues raised by the PTM.

Later, in early 2022, when the ANP supported the vote of no-confidence against the PTI government, many commentators believed they had been vindicated for calling the ANP out as a pro-establishment party.

The politics of ANP had traditionally revolved around issues such as provincial autonomy, stopping the Kalabagh dam's construction, and giving the province a Pushtun identity. It achieved its goals of provincial autonomy after the passage of the 18th Amendment in 2010 during the Pakistan People's Party-led federal government. That amendment also helped the province secure the name of "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa" for the erstwhile North Western Frontier Province (NWFP), thus resolving the issue of a Pushtun identity. The Kalabagh Dam, too, has been buried somewhere.

The feudal class can, thus, no longer hope to influence people the way they used to. The ANP ranks, though, still accommodate a large number of these feudal lords who could not perform in a considerably open society

However, joining the likes of PML-N and PPP to orchestrate the no-confidence vote against Imran Khan's government proved to be a disaster for the ANP. On the one hand, it supported the ouster of the PTI government, but on the other, it failed to secure a ministry in the deal. The people, though, easily saw through this move.

ANP tried to represent the other ethnic nationalities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, but given certain entrenched ethnic and nationalist posturing by some of its ideologues and intellectuals, it could not penetrate these communities, especially in the Hazara Division and the southern districts of the province.

The people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are not feudal the way many in Sindh or Balochistan may be. The middle class here is growing because of an influx of remittances from overseas. The feudal class can, thus, no longer hope to influence people the way they used to. The ANP ranks, though, still accommodate a large number of these feudal lords who could not perform in a considerably open society.

The people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are, by and large, swing emotionally. They buy the victim cards willingly. In 2002, they voted for the Mutahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) — an amalgamation of six or so religious parties. At the time, the MMA sold them on the narrative of a bigger hegemon/victimiser, the United States, which had launched an offensive in neighbouring Afghanistan.

In 2024, the people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have before them a greater and more obvious victim in Imran Khan. Imran had ruled the province for eight years and was now ousted, shot, jailed, convicted in several trumped-up cases, and his party deprived of its election symbol. Imran Khan played the victim card well, openly exposing the establishment. The vote for PTI in Pakistan in general and in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in particular, vented the public's fury against the establishment because people think it has been using every cruel trick in the book against Imran Khan while other political parties, including the ANP, were its silent accomplice.