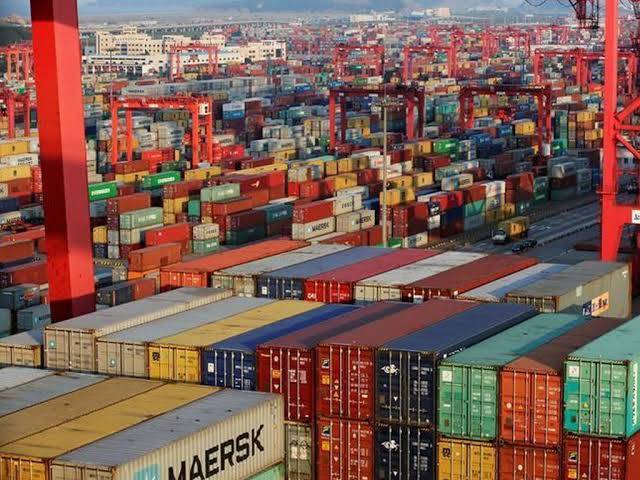

Thousands of containers packed with essential food items, raw materials, and medical equipment continue to pile up at Karachi's Port Qasim as Pakistan grapples with a desperate foreign exchange crisis that is threatening to bring economic activity to a standstill.

A critical scarcity of dollars has rendered banks hesitant at issuing new letters of credit for importers, sharply hitting an economy already squeezed by galloping inflation and dismal growth prospects. Prices of food commodities in local retail markets is also increasing abruptly, as imports are docked at the port waiting for clearance.

"I have been in the business for the past 40 years, and I have not witnessed a worse time," said Abdul Majeed, an official with the All Pakistan Customs Agents Association.

He spoke from an office near the Karachi port, where shipping containers – packed with lentils, pharmaceuticals, diagnostic equipment, and chemicals for Pakistan's manufacturing industries – have been stuck for weeks, even months, waiting on payment guarantees.

"We've got thousands of containers stranded at the port because of the shortage of dollars," said Maqbool Ahmed Malik, chairman of the customs association, adding that operations had been "down at least 50%".

This week, the State Bank of Pakistan's foreign exchange reserves fell to less than $6 billion — their lowest in nine years — as obligations of more than $8 billion will due in the first quarter of 2023 alone. These meagre reserves are enough to pay for just a month of imports, according to independent experts.

Pakistan's economy has been crumbling alongside a simmering political crisis, with the Rupee plummeting and inflation at the highest level in decades, while devastating floods and recurring crises in the energy sector have added further pressure.

The country's enormous debt — currently $274 billion, or nearly 90% of gross domestic product — and the endless effort to service it makes Pakistan particularly vulnerable to economic shocks.

Islamabad has pinned all its hopes of survival on an IMF deal, but the latest payment from the IMF extended fund facility has been pending since September 2022. The global lender of last resort is demanding the complete withdrawal of subsidies on petroleum products and electricity, which would further burden the population of over 235 million with cost of living crises.

Acquiescing to the harsh IMF conditionalities would also be political suicide for the ruling PDM coalition, which has faced unrelenting public pressure from former premier and PTI chairman Imran Khan for ten months. Analysts say Khan believes economic chaos and political instability might help Khan achieve his goal of early elections, but doing so comes at the expense of everything else. Prime minister Shehbaz Sharif recently urged the IMF to give Pakistan some "breathing space" as it tackles this "nightmarish" scenario.

A critical scarcity of dollars has rendered banks hesitant at issuing new letters of credit for importers, sharply hitting an economy already squeezed by galloping inflation and dismal growth prospects. Prices of food commodities in local retail markets is also increasing abruptly, as imports are docked at the port waiting for clearance.

"I have been in the business for the past 40 years, and I have not witnessed a worse time," said Abdul Majeed, an official with the All Pakistan Customs Agents Association.

He spoke from an office near the Karachi port, where shipping containers – packed with lentils, pharmaceuticals, diagnostic equipment, and chemicals for Pakistan's manufacturing industries – have been stuck for weeks, even months, waiting on payment guarantees.

"We've got thousands of containers stranded at the port because of the shortage of dollars," said Maqbool Ahmed Malik, chairman of the customs association, adding that operations had been "down at least 50%".

This week, the State Bank of Pakistan's foreign exchange reserves fell to less than $6 billion — their lowest in nine years — as obligations of more than $8 billion will due in the first quarter of 2023 alone. These meagre reserves are enough to pay for just a month of imports, according to independent experts.

Pakistan's economy has been crumbling alongside a simmering political crisis, with the Rupee plummeting and inflation at the highest level in decades, while devastating floods and recurring crises in the energy sector have added further pressure.

The country's enormous debt — currently $274 billion, or nearly 90% of gross domestic product — and the endless effort to service it makes Pakistan particularly vulnerable to economic shocks.

Islamabad has pinned all its hopes of survival on an IMF deal, but the latest payment from the IMF extended fund facility has been pending since September 2022. The global lender of last resort is demanding the complete withdrawal of subsidies on petroleum products and electricity, which would further burden the population of over 235 million with cost of living crises.

Acquiescing to the harsh IMF conditionalities would also be political suicide for the ruling PDM coalition, which has faced unrelenting public pressure from former premier and PTI chairman Imran Khan for ten months. Analysts say Khan believes economic chaos and political instability might help Khan achieve his goal of early elections, but doing so comes at the expense of everything else. Prime minister Shehbaz Sharif recently urged the IMF to give Pakistan some "breathing space" as it tackles this "nightmarish" scenario.