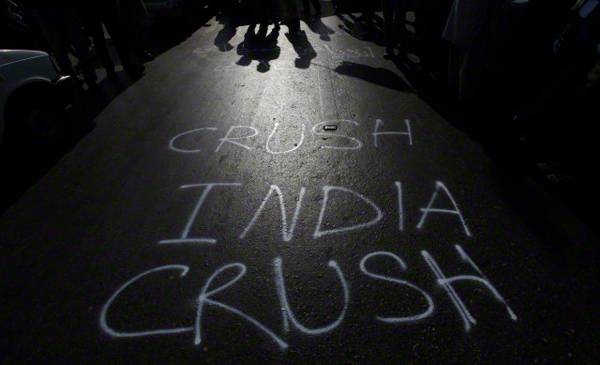

When Pakistan observed February 5 as ‘Kashmir Solidarity Day’, Islamabad was more belligerent than previous years. Besides Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s tough talk in Muzaffarabad on the day a number of rallies by extremists pointed towards a hard line, the state had preferred to send a message to India. The main reason could be the stalled process of dialogue that followed the unilateral cancellation of Foreign Secretary-level talks by New Delhi and the continuous exchange of fire on borders.

Except for getting the hardline constituency involved in the renewed Kashmir ‘strategy’, though only at the public posturing level, Sharif has been treading a cautious path after he took over in May 2014. Right from his campaigning to initial statements as Prime Minister, he did not sound belligerent towards India. He invoked the 1999 Lahore Declaration, of which he and the former Prime Minister A B Vajpayee were the architects, to pick up the threads on the peace process. He did not come clear on Pakistan’s Kashmir policy and continued to go in circles, singing the peace tune for resolving all outstanding problems with India. However, at the same time he did not oppose any hardliner as well. Since Sharif owes his return to power partly to extremists in Pakistan, he continued to keep his Kashmir policy under wraps except a few pronouncements. He tried to distance himself from making a direct or meaningful reference over Kashmir when it mattered a lot. Much against the reservations of Army, Sharif accepted the invitation of Prime minister Narendra Modi to attend his swearing in ceremony last year.

But today Sharif finds himself in a tight spot. Under tremendous pressure from the hardline constituency and a strong section in Pakistan Army he is forced to toe a line that challenges India. However, commemorating February 5 is being debated in Pakistani media raising questions about its relevance. Many analysts are of the opinion that this is to reinforce the confidence of Jihadi groups, who apparently vow to “liberate Kashmir” but essentially are an existential threat to Pakistan itself.

To re-infuse official confidence on days like February 5 is no more than posturing to keep Pakistan’s Kashmir constituency as well as separatists in the valley in good humour. There is no denying the fact that Pakistan is a principle party to Kashmir dispute and its involvement in final resolution cannot be ignored and is rather inevitable. But the way Islamabad has been handling Kashmir during past 65 years is full of flaws and backward moments. In its editorial last year, Pakistani newspaper Dawn had observed that the country’s Kashmir policy has all along been dominated by the security establishment.

“Even as Kashmir Day was observed on Wednesday, few people realised the enormous damage done to the cause of Kashmir’s freedom by Pakistan’s past cultivation of non-state actors. True, some political governments were mindful of the hazards inherent in such a policy but they were helpless in the face of the military’s stiff opposition to their views. The generals insisted that they alone knew how to run Pakistan’s security policy. Conceding this point meant handing over to the army the gamut of security issues from Afghanistan and Kashmir to N-weapons,” the newspaper wrote. This year too the media is critical of creating a euphoria on the day.

On the face of it, Islamabad has been maintaining that it was only extending diplomatic, moral and political support to Kashmir. But in reality it has been much more than that. When armed rebellion erupted in Kashmir in 1989, this challenge to Indian rule was by and large indigenous in nature even as the material support was given by Pakistan. With the passage of time, Pakistan changed its complexion and opened up the gates for external elements thus hijacking not only the movement but the discourse as well. It continues to hold key to the political discourse in the separatist camp and it has not encouraged independent thinking on Kashmir. While it boasts about being the only benefactor of Kashmiris it has miserably failed in allowing space for a Kashmiri discourse and exerting as a genuine party.

In case Pakistan would have acted with a policy to only help Kashmir “cause”, it would not have come under the “burden” of the tribal raid of 1947, accepting Simla agreement “under duress”, starting militancy in Kashmir and now taking refuge by allowing the extremists to take the centre stage in advocating the Kashmir cause. Pakistan has failed to realize that the biggest damage to Kashmir was caused after 9/11 when it was linked to the so-called international terror network and the real political dispute of Kashmir was defamed at the international level. This was also the result of involvement of those actors who in one or the other way owed allegiance to those who were operating in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Pakistan became miserably weak at diplomatic level and could not fend off the Indian offensive.

It is a fact that Nawaz Sharif did not get a positive response from New Delhi but in spite of that Islamabad continued to promote the bilateral relations through trade and commerce and showed keen interest in improving non-political relations. Today, trade between the two countries is an important area of engagement and for the sake of it, they have even sacrificed the cross Line of Control (LoC) trade which had emerged as an important Confidence Building Measure. Pakistan may observe a Kashmir Day with much fanfare but the fact is that its Kashmir fatigue is quite visible in its real dealings. Policy experts and even some important functionaries in the government have conceded (in private) that Pakistan has been paying a huge price on account of terrorism in the last decade or so and Kashmir is one of the reasons for that. One can empathize with Pakistan as far as its terrible internal situation is concerned though it is not mainly due to Kashmir. The flawed policy of giving in to the security establishment, as suggested by Dawn, has lot to do with Pakistan’s present dilemmas over Kashmir. There could be many more questions Pakistan will have to answer over Kashmir. However, the concern must revolve around the stability of Pakistan. Resolving Kashmir is an unavoidable task both India and Pakistan must take up not only for peace in Pakistan, but in entire South Asia.

At the same time India must not take “undue advantage” of Pakistan’s vulnerabilities and continue to shrug off the resolution of Kashmir. Engagement between the two countries on mutual terms is must and for creating an atmosphere of trust and confidence within Kashmir it is important that New Delhi and Islamabad start talking. However, Pakistan also needs to change its obsolete way of projecting Kashmir as a “cause”. The process has to be pragmatic and meaningful and the rhetoric has not worked in the past nor will do in future. In Delhi Modi needs to see Kashmir through the prism of a problems that have to be resolved. It cannot be ignored as a mere law and order issue. Celebrating a turn out in elections is good but unless it is supplemented and complimented with a serious political engagement, Kashmir will continue to sit on a volcano of unrest that has a potential to explode to an unimaginable level.

Except for getting the hardline constituency involved in the renewed Kashmir ‘strategy’, though only at the public posturing level, Sharif has been treading a cautious path after he took over in May 2014. Right from his campaigning to initial statements as Prime Minister, he did not sound belligerent towards India. He invoked the 1999 Lahore Declaration, of which he and the former Prime Minister A B Vajpayee were the architects, to pick up the threads on the peace process. He did not come clear on Pakistan’s Kashmir policy and continued to go in circles, singing the peace tune for resolving all outstanding problems with India. However, at the same time he did not oppose any hardliner as well. Since Sharif owes his return to power partly to extremists in Pakistan, he continued to keep his Kashmir policy under wraps except a few pronouncements. He tried to distance himself from making a direct or meaningful reference over Kashmir when it mattered a lot. Much against the reservations of Army, Sharif accepted the invitation of Prime minister Narendra Modi to attend his swearing in ceremony last year.

But today Sharif finds himself in a tight spot. Under tremendous pressure from the hardline constituency and a strong section in Pakistan Army he is forced to toe a line that challenges India. However, commemorating February 5 is being debated in Pakistani media raising questions about its relevance. Many analysts are of the opinion that this is to reinforce the confidence of Jihadi groups, who apparently vow to “liberate Kashmir” but essentially are an existential threat to Pakistan itself.

To re-infuse official confidence on days like February 5 is no more than posturing to keep Pakistan’s Kashmir constituency as well as separatists in the valley in good humour. There is no denying the fact that Pakistan is a principle party to Kashmir dispute and its involvement in final resolution cannot be ignored and is rather inevitable. But the way Islamabad has been handling Kashmir during past 65 years is full of flaws and backward moments. In its editorial last year, Pakistani newspaper Dawn had observed that the country’s Kashmir policy has all along been dominated by the security establishment.

“Even as Kashmir Day was observed on Wednesday, few people realised the enormous damage done to the cause of Kashmir’s freedom by Pakistan’s past cultivation of non-state actors. True, some political governments were mindful of the hazards inherent in such a policy but they were helpless in the face of the military’s stiff opposition to their views. The generals insisted that they alone knew how to run Pakistan’s security policy. Conceding this point meant handing over to the army the gamut of security issues from Afghanistan and Kashmir to N-weapons,” the newspaper wrote. This year too the media is critical of creating a euphoria on the day.

On the face of it, Islamabad has been maintaining that it was only extending diplomatic, moral and political support to Kashmir. But in reality it has been much more than that. When armed rebellion erupted in Kashmir in 1989, this challenge to Indian rule was by and large indigenous in nature even as the material support was given by Pakistan. With the passage of time, Pakistan changed its complexion and opened up the gates for external elements thus hijacking not only the movement but the discourse as well. It continues to hold key to the political discourse in the separatist camp and it has not encouraged independent thinking on Kashmir. While it boasts about being the only benefactor of Kashmiris it has miserably failed in allowing space for a Kashmiri discourse and exerting as a genuine party.

In case Pakistan would have acted with a policy to only help Kashmir “cause”, it would not have come under the “burden” of the tribal raid of 1947, accepting Simla agreement “under duress”, starting militancy in Kashmir and now taking refuge by allowing the extremists to take the centre stage in advocating the Kashmir cause. Pakistan has failed to realize that the biggest damage to Kashmir was caused after 9/11 when it was linked to the so-called international terror network and the real political dispute of Kashmir was defamed at the international level. This was also the result of involvement of those actors who in one or the other way owed allegiance to those who were operating in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Pakistan became miserably weak at diplomatic level and could not fend off the Indian offensive.

It is a fact that Nawaz Sharif did not get a positive response from New Delhi but in spite of that Islamabad continued to promote the bilateral relations through trade and commerce and showed keen interest in improving non-political relations. Today, trade between the two countries is an important area of engagement and for the sake of it, they have even sacrificed the cross Line of Control (LoC) trade which had emerged as an important Confidence Building Measure. Pakistan may observe a Kashmir Day with much fanfare but the fact is that its Kashmir fatigue is quite visible in its real dealings. Policy experts and even some important functionaries in the government have conceded (in private) that Pakistan has been paying a huge price on account of terrorism in the last decade or so and Kashmir is one of the reasons for that. One can empathize with Pakistan as far as its terrible internal situation is concerned though it is not mainly due to Kashmir. The flawed policy of giving in to the security establishment, as suggested by Dawn, has lot to do with Pakistan’s present dilemmas over Kashmir. There could be many more questions Pakistan will have to answer over Kashmir. However, the concern must revolve around the stability of Pakistan. Resolving Kashmir is an unavoidable task both India and Pakistan must take up not only for peace in Pakistan, but in entire South Asia.

At the same time India must not take “undue advantage” of Pakistan’s vulnerabilities and continue to shrug off the resolution of Kashmir. Engagement between the two countries on mutual terms is must and for creating an atmosphere of trust and confidence within Kashmir it is important that New Delhi and Islamabad start talking. However, Pakistan also needs to change its obsolete way of projecting Kashmir as a “cause”. The process has to be pragmatic and meaningful and the rhetoric has not worked in the past nor will do in future. In Delhi Modi needs to see Kashmir through the prism of a problems that have to be resolved. It cannot be ignored as a mere law and order issue. Celebrating a turn out in elections is good but unless it is supplemented and complimented with a serious political engagement, Kashmir will continue to sit on a volcano of unrest that has a potential to explode to an unimaginable level.